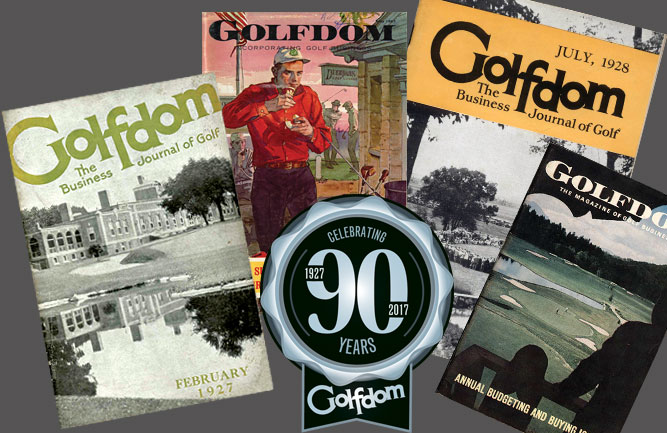

Mr. Golf’s magazine through the years

“When Golfdom’s first issue appeared in February 1927, Charles Lindbergh had taken his big chance, Calvin Coolidge was settling into the president’s chair and Americans were taking long shots on the market and prohibition booze. Nearly 4,000 golf courses existed in 1927, the majority of which were nine holes. Looking at those courses as a potential market as well as a playground, Golfdom started as the first golf business journal.”

Herb Graffis

Co-founder of Golfdom

They called him “Mr. Golf.” No name could be more fitting for Herbert Butler Graffis.

They called him “Mr. Golf.” No name could be more fitting for Herbert Butler Graffis.

His achievements — often accomplished in partnership with his younger brother Joe — speak volumes about his impact on the game:

- Launched Golfing, the predecessor to Golf magazine, in 1933.

- Created the National Golf Foundation in 1936.

- Joined up with Grantland Rice to found the Golf Writers Association of America.

- Ghost-wrote Tommy Armour’s classic instruction book, “How to Play Your Best Golf All the Time.”

- Helped organize the first GCSAA Conference in 1928.

- Spearheaded the first PGA Show.

- And 72 years ago this month, he and his brother began publishing a modest, digest-sized magazine called Golfdom.

The Industry’s Bible

Designed to serve superintendents, professionals and club managers, Golfdom was the industry’s first business journal. It featured articles on everything from turfgrass diseases to table settings. It was a smorgasbord of content that educated, inspired, compelled and even preached.

Looking back at Golfdom is like taking a trip through the history of American golf. Alistair MacKenzie wrote on design. Sam Snead and Gene Sarazen were contributors. Legendary researchers like O.J. Noer, Joe Duich and Jim Beard used the pages of Golfdom to raise the standard of turfgrass science. Golfdom’s content helped to introduce and shape the practices that every superintendent, professional and manager use today. It was, quite simply, the industry’s bible.

The Agenda

Perhaps more important than the articles was the agenda. Graffis used Golfdom as a bully pulpit to prod the industry into the modern era. He believed that the growth of golf was inextricably linked to the professionalism of the people who managed the clubs, taught the game and managed the playing field.

Above all, he was a tireless advocate of superintendents. He used the pages of Golfdom to crusade for things taken for granted today: collegiate turf programs, continuing education, research, better compensation and benefits, improved maintenance facilities and, most of all, professional recognition. Graffis is credited with popularizing the title “golf course superintendent.”

“Sooner or later, clubs have to face up to the fact that it takes more than a man with a strong back and a green thumb to handle the job,” he wrote. “Lack of good planning and failure to make intelligent use of modern materials and equipment can easily cost clubs more than the extra salary they would pay for a good superintendent.”

Although he believed that superintendents were the game’s “unsung heroes,” he took umbrage at the notion that they were the “forgotten men” of golf. “The forgotten man business can be ruled out,” he wrote. “There is that old Shakespearean line, ‘The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars but in ourselves.’ If any superintendent is forgotten (now), he better examine himself. Maybe he just doesn’t look and act as though he is worth a higher salary.”

Although Graffis felt the superintendent had to pull himself up by his own bootstraps, he also understood the harsh realities of the profession. “The club manager is around where he can hear and handle any complaints involving his operation. The pro hears what is wrong with his department and he can settle the problems. But the superintendent is far away behind the grass curtain, and he can’t tell his story, especially when his is handling the grave emergencies that seem to be fairly frequent in the nature of the golf course operation.” And he always saw the bottom line. “If everything is going along in great shape, anybody can run a golf course. But when there’s heck to pay, the emergency requires a first-class superintendent.”

Piss and vinegar

Under Graffis’ hand, Golfdom thrived for half a century. But Herb’s ability to keep Golfdom moving forward declined as he reached his 70s. In 1976, after the death of his brother, he sold the publication. After several changes of ownership and names, Golfdom ceased publication in 1981.

Golfdom passed, but Herb lived on as the grand old man of the game. There isn’t an industry honor he didn’t receive: distinguished service awards from GCSAA and PGA; induction in the Hall of Fame; even one named for him, the NGF Graffis Award. He died in 1989. He was 95 years old and, as an industry historian says with a smile, “Full of piss and vinegar to the end.”

Editor’s Note: The above information was originally published in the January 1999 issue that re-launched Golfdom.

Related: Memories of Mr. Golf

Related: Golfdom Gallery: 90th anniversary edition

Photos: Golfdom