Super Science: A million ways for grass to die in the winter

By my count, this is the 13th consecutive year I have written a snow mold article for Golfdom, and in each of the previous 12 years, I have focused solely on snow mold. However, the past few winters in the Midwest have clearly demonstrated that what can kill your grass from winter to winter can be completely different. In one winter, it might be early winter rainfalls and heavy late-winter snowfall that leads to destructive snow mold outbreaks. Next winter, an absence of snow could lead to widespread desiccation injury. In yet another, it could be snow melt events that then freeze and lead to widespread crown hydration or ice injury.

But no matter the conditions, something can kill or injure your grass. Let’s review the various types of winter injury that can occur and the best methods for preventing each one.

Snow mold

Snow mold is one of the most common forms of winter injury but fortunately also one of the most straightforward to prevent. Snow mold is a generic term that encompasses any fungal infection of turfgrass over the winter months and is most commonly one of the three primary snow molds; pink snow mold (Microdochium nivale), gray snow mold (Typhula incarnata) or speckled snow mold (Typhula ishikariensis).

Preventing snow mold is typically done by making one or two fungicide applications in late fall. However, winter rainfall or snowmelt events can rapidly degrade those fungicides and leave the turf susceptible to snow mold development later in the winter. These exact conditions led to widespread snow mold breakthrough during the winter of 2022-2023 across large swaths of the country. To combat this, it’s important to apply a highly effective fungicide mixture in late fall that maximizes injury to the fungal population and also make that application as late in the fall as possible to avoid late fall rainfall events. Cultural suppression of snow mold is typically done by avoiding late fall applications of nitrogen fertilizer, but this only results in modest decreases in snow mold in most cases. Research from professor Doug Soldat at Wisconsin has shown that potassium fertilization can increase snow mold on creeping bentgrass but professors Bruce Clarke and Jim Murphy from Rutgers have shown that it can decrease snow mold on annual bluegrass, so knowing the predominant grass species on your course can help drive your fertilization priorities.

Snow mold pressure was lower than normal across most of the northern U.S. last winter, but there were pockets where it was severe. Snow mold was limited in our own research trials in southern Wisconsin, central Wisconsin and Minnesota due to dry and cold conditions. Our trial at Marquette GC in Marquette, Mich., had decent snow mold pressure at 54-percent disease in the non-treated controls (Figure 1), though normally this site averages 95- to 100-percent disease. Most treatments that included two or three active ingredients provided exceptional snow mold control in this lower pressure environment. Special thanks to our host snow mold superintendents Aaron Hansen at Wausau CC, Matt McKinnon at Cragun’s Resort, Craig Moore at Marquette GC and Jake Ryan at Northland CC.

To see the full results from all our snow mold research please visit here.

Desiccation

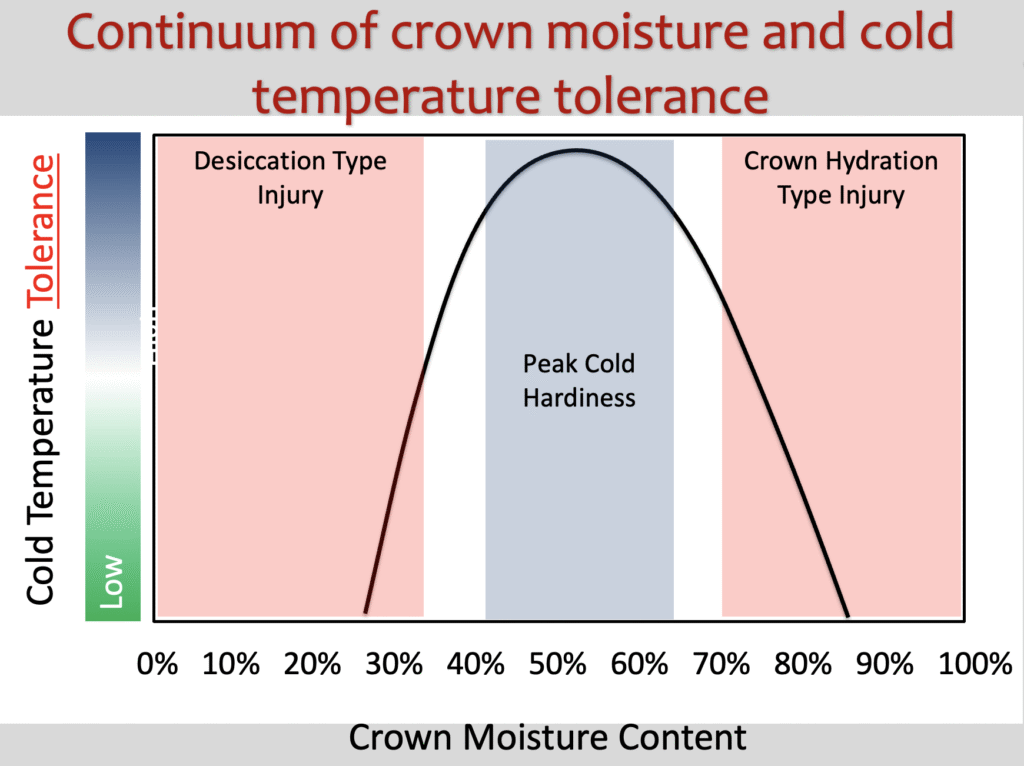

Desiccation injury was the biggest story across the western Great Lakes region in Wisconsin, Iowa, Illinois and other states this spring. A very dry fall followed by record dry conditions in January and a severe cold snap led to widespread injury on creeping bentgrass. Though the water needs of the plant are reduced in winter because it’s mostly in a dormant state, those water needs aren’t zero, so prolonged plant water loss in excess of water intake will lead to injury and potentially plant death. Previous research by Bill Kreuser, Ph.D. from GreenKeeper found that crown water content below approximately 50 percent results in an increased chance of injury to winter desiccation (Figure 2). Elevated parts of the golf course, locations that are exposed to more wind, turf on sandy soils and sites with significant thatch are all more susceptible to winter desiccation injury.

Kreuser has more experience studying winter desiccation injury and prevention strategies than just about anyone. In 2019, Kreuser wrote an article for Golfdom detailing the results of his research on desiccation injury prevention. In short, their results found that physical barriers that retained moisture such as permeable and impermeable covers and heavy sand topdressing provided the best protection against desiccation injury. Other treatments like wetting agents, pigments or antitranspirant products had minimal effects on reducing winter injury.

The results from Kreuser’s research matches what we observed in the field this spring. Courses that covered greens using a permeable cover had much less winter injury this year compared to those that didn’t because the covers retained more moisture for the plant (Figure 3).

Ice encasement and crown hydration

Crown hydration occurs when water freezes inside the cells of the plant’s crown, rupturing the membrane and leading to cell death. This normally occurs when a rainfall is followed by a rapid and extreme drop in temperatures.

Ice encasement occurs following prolonged ice cover that decreases oxygen and increases toxic gases like methane, which can lead to plant death in as little as 30 days for annual bluegrass or as much as 120 days or more on creeping bentgrass. Ice injury is more common in the Great Lakes and Northeast because of the many freeze-thaw cycles that can occur during winter in these two regions.

If desiccation is a case of too little water, crown hydration and ice encasement are usually a case of too much. While we can’t control how much water falls from the sky in the winter, we have more control over what happens to that water once it falls. Providing for ample surface drainage is critical to move water off the putting surfaces. This includes sand dams and other water obstructions at the collar that prevent rain and melting snow from fully flowing off the putting surface. In addition, impermeable covers may provide protection by keeping the water from reaching the crown while both impermeable and permeable covers may provide some ice encasement prevention by creating a layer of air separation between the ice and the turf.

Direct low temperature injury

Every organism has a minimum temperature at which they can survive, and while this isn’t something we often think about in turfgrass, different grass species have been reported to have different minimum temperature thresholds.

James Beard, Ph.D., in his seminal textbook, “Turfgrass: Science and Culture,” reported that annual bluegrass was susceptible to direct low temperature injury beginning at -4 degrees F while creeping bentgrass could survive temperatures up to -40 degrees F. Usually, low temperature injury hasn’t been considered a common type of winter injury, but Kreuser has observed that plants stressed from drought are much more sensitive to low temperature injury than those that aren’t. This would support what we saw in Wisconsin and surrounding states this past winter when very dry conditions were followed by a severe cold snap of temperatures dipping down below -20 degrees F. Likely the only effective method to prevent direct low temperature injury is physical protection through the addition of covers and possibly through the application of heavy sand topdressing in late fall.

The best defense is a healthy plant

All the forms of winter injury discussed above have different mechanisms that kill the plant in different ways. However, in all these cases, the best defense against winter injury is a healthy plant going into winter. A healthy plant has ample carbohydrates stored up to last the long winter ahead and can better endure stresses.

One of the most common factors leading to winter injury is sunlight, especially south-facing sunlight during the fall (Figure 4). Less sunlight means less photosynthesis which means less excess energy to convert to carbohydrates for long-term storage during the winter. Assessing where shade is a problem during both the summer and fall is one of the most effective ways to reduce all forms of winter injury.

The desiccation injury from this past winter was exacerbated by a significant drought last fall. Because the plant’s water needs aren’t as high in the late fall and the season is ending soon, we often don’t think to irrigate very often during this period, but adequate water in the fall is crucial for the plant.

Mechanical stresses during the fall can also stress the turf and lead to winter injury. I visited a course this spring that had mild to moderate desiccation injury through much of the course, but severe injury that required overseeding in areas where they verticut last fall. The stress from the verticutting coupled with the drought and cold stress made the injury to these areas much more severe than over the rest of the course.

Want to participate in winter injury research?

Is winter injury a concern at your golf course? Do you want to help conduct research that will help us learn more about preventing winter injury?

If you said yes to both of those questions, then you should join our WinterTurf research team! WinterTurf is a research project supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Institute of Food and Agriculture and Specialty Crop Research Initiative under award number 2021-51181-35861. A critical part of the project is having golf course superintendents from around the world participate in the project by submitting regular observations from their golf course throughout the winter. The research team then uses the data provided by the superintendents to better understand the conditions that lead to various forms of winter injury, which will then help us develop better prevention strategies.

To learn more about the WinterTurf project please visit here. To learn more about data collection at your course and to sign up, please visit here.

Paul Koch, Ph.D., is a professor at the University of Wisconsin – Madison. He can be reached at plkoch@wisc.edu.