Why the winter of 2022-2023 was a proverbial snow mold bloodbath

Snow mold is just like real estate … it’s all about location, location, location. For many areas of the southern Midwest and Northeast, the lack of snow last winter resulted in almost no snow mold at all. However, for those in more northern locales and the Rocky Mountain West, it was one of the more damaging snow mold years in recent memory.

In many cases, severe damage occurred on courses that spent tens of thousands of dollars treating their golf courses with fungicide programs that had shown great success in university research, including our own. I believe it was the most widespread breakout of the disease in treated areas over the 18 years I have researched snow mold at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

In other words, for many, the winter of 2022-2023 was a proverbial snow mold bloodbath.

(Fig. 1) Last year our research site at Giant’s Ridge GC in Biwabik, Minn., had a lot of snow mold in non-treated areas but much less breakthrough on treated plots due to less December rain compared to our other sites. (Photo: Paul Koch, Ph.D.)

What went wrong?

Nearly all areas affected by snow mold experienced above-average snowfall last winter, but not all places affected by heavy snow had severe snow mold damage (Figure 1). The difference between the two situations lies in when much of the snow fell and what else fell during the winter.

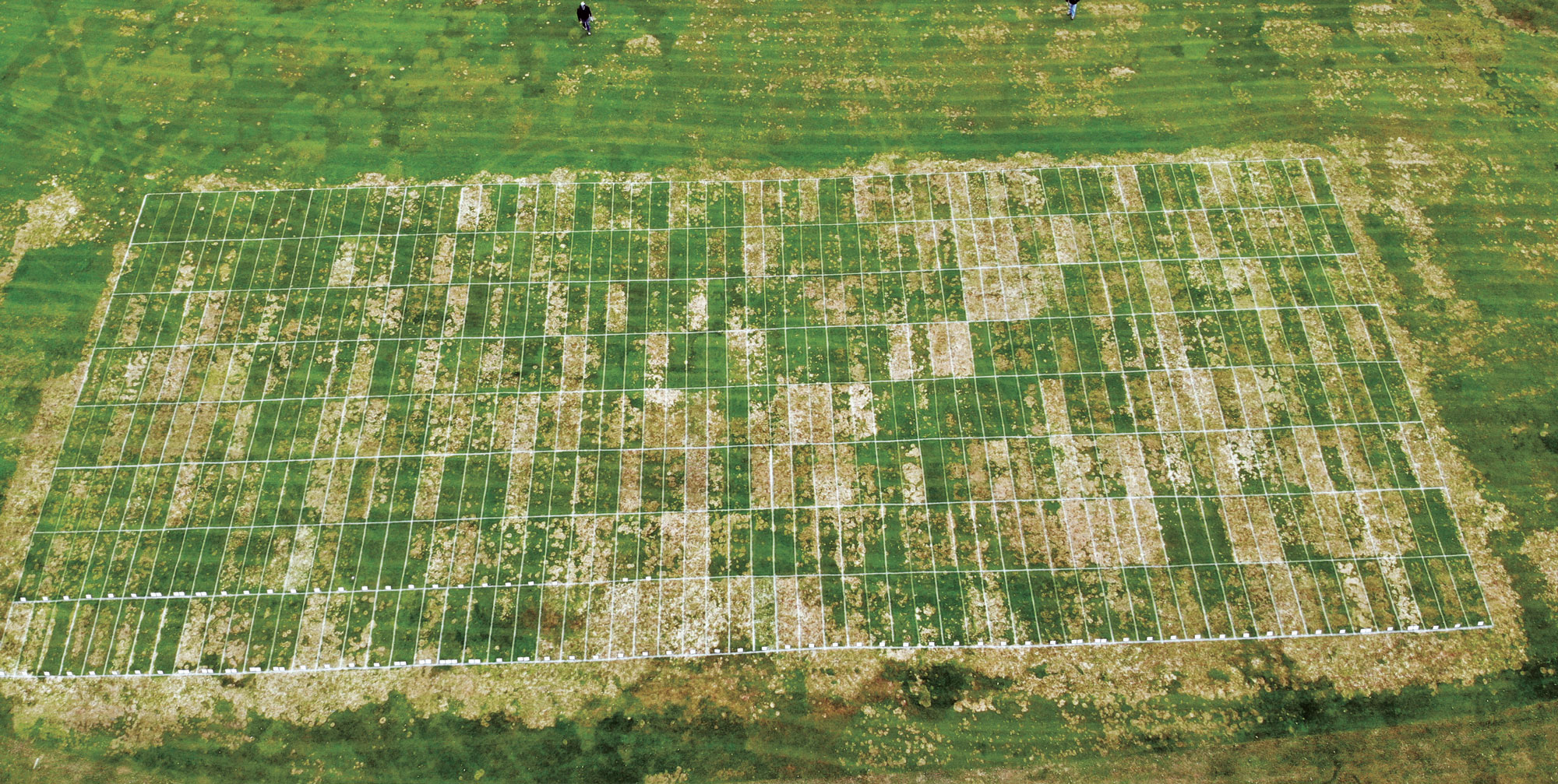

Let’s use our research trial at Marquette (Mich.) Golf Course as a case study. We tested more than 120 treatments that were a mixture of current products on the market and experimental mixtures that may or may not be on the market in a few years. Marquette GC always has a lot of snow mold and is a strong test of products. In most years, 50 to 75 percent of the treatments we test provide good to excellent snow mold control. This year, that number was more like 10 to 20 percent (Figure 2).

Why did the control drop last winter? The likely explanation is twofold. First, a couple of rain events occurred in early December — approximately six weeks after our Oct. 27 application date. Based on our previous research, we know that winter rainfall dramatically reduces snow mold fungicide concentrations in the plant and leaves them susceptible to snow mold infection.

However, winter rainfalls don’t usually lead to a lot of snow mold breakthroughs because the initial fungicide application significantly knocks back the fungal population to the point where it rarely causes disease.

That leads to the second part of the problem at Marquette and many other northern locales this year, heavy spring snowfall. Marquette received 46 inches of snow in March, more than double its average amount of 22 inches.

This late-season snowfall led to optimal snow mold infection conditions months after much of the fungicide dissipated during the December rains. This combination of early winter rains and heavy spring snowfall created an almost impossible scenario for snow mold fungicides. Unfortunately, the result for many was significant snow mold damage.

A very similar scenario with early winter rains and heavy spring snowfall also occurred at our research site in McCall, Idaho. The result was the same, a lot of snow mold in treated areas.

(Fig. 2) Aerial view of our research trial at Marquette GC in Marquette, Mich. Though there are some green rectangles, there is much more disease breakthrough than we typically experience. (Photo: Tom Steigauf)

The effects of climate change?

We don’t want to overreact to one bad winter, but some trends related to climate change are starting to take shape.

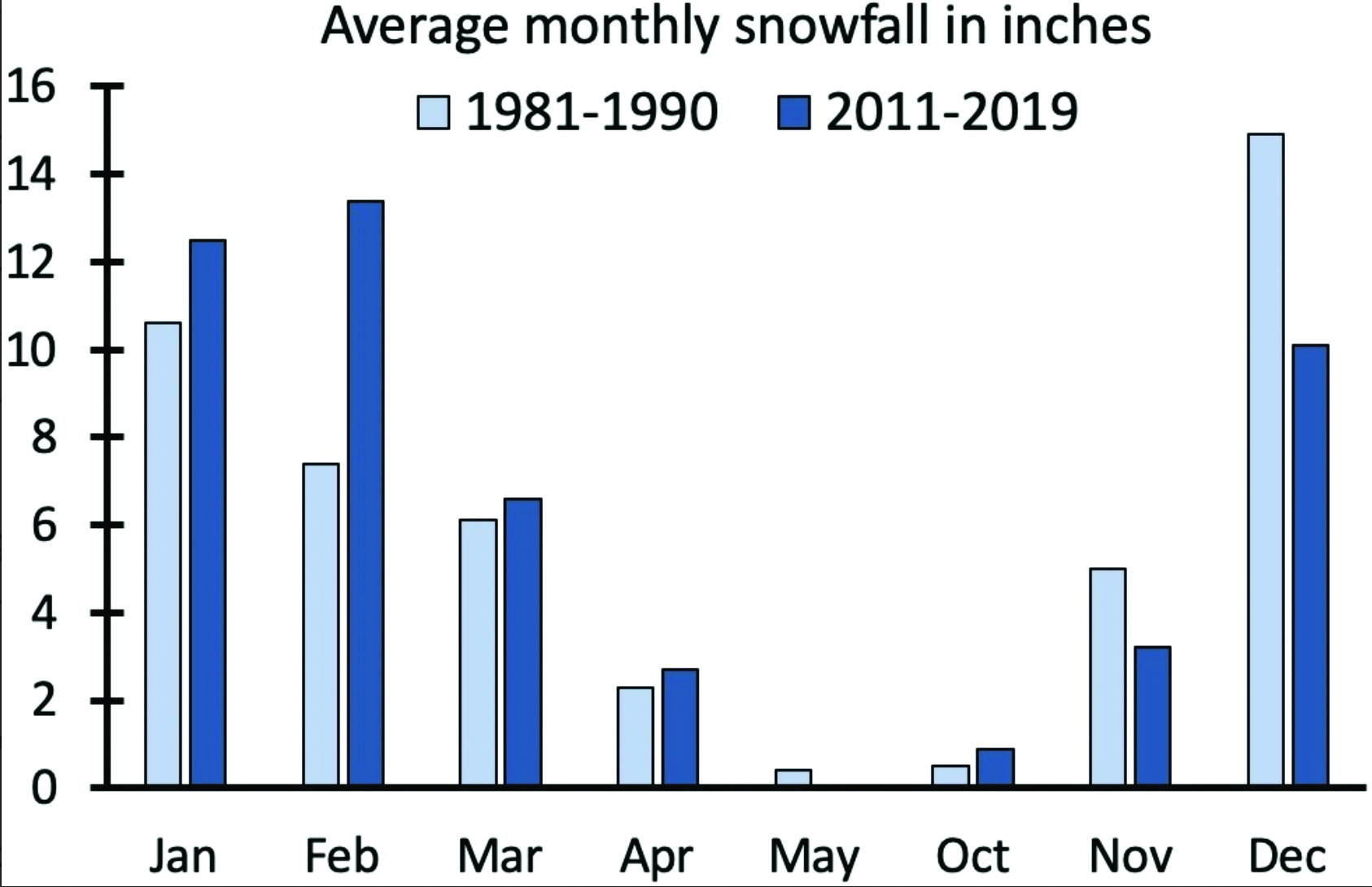

(Fig. 3) Climate researchers from the University of Wisconsin-Madison have shown that total seasonal snowfall for Madison and other Midwestern locations has largely stayed the same over the past 40 years. In the last 10 years, less snow has fallen in late fall/early winter and more has fallen in late winter/early spring. (Figure taken from this site.)

First, fall conditions are warmer than previous years. This results in less late fall/early winter snow in many locations. It also prevents the plants from fully hardening once the snow arrives. This makes plants more susceptible to snow mold. Second, winter rainfall and snowmelt events are becoming more common, even in northern locales.

As we just discussed, this dissipates snow mold fungicide protection early in the season and makes disease breakthroughs more likely. Third, late winter/early spring snowfall is increasing (Figure 3). This adds to the pressure on snow mold products that were applied 4 to 6 months earlier, also increasing the likelihood of disease breakthroughs.

Many people, including myself, assumed that warmer winters caused by climate change would decrease the overall severity of snow mold across the north. The reality is much more complex and only increases the burden on superintendents to achieve acceptable snow mold control.

Greens vs. fairways

In one of my first years working at the University of Wisconsin, I recall a fungicide sales rep telling me confidently that, “snow mold doesn’t occur on putting greens.”

I know this isn’t true since I’ve occasionally seen snow mold breakthroughs on greens. But one interesting note from our research this year did reveal the dramatic differences in snow mold pressure between greens and fairways.

One company asked to have snow mold products tested on putting greens last winter, so we worked with the local superintendents at Wausau Country Club in Schofield, Wis., Marquette GC and McCall GC to test a small subset of treatments on a practice or chipping green at each course.

(Fig. 4) Snow mold pressure at McCall (Idaho) GC was much higher on the fairway (L) compared to the chipping green (R) just 500 yards away. The same difference was also observed at our research sites in Marquette, Mich., and Wausau, Wis. (Photos: Paul Koch, Ph.D.)

The differences in snow mold severity between the fairway and putting green plots were massive. At Wausau, the snow mold severity on fairways was 31.3 percent and on the chipping green it was 0.5 percent; in Marquette, disease on fairways was 72.5 percent and 26.3 percent on the chipping green; and at McCall, we saw 99 percent disease on fairways and 6.3 percent on greens (Figure 4).

In my opinion, the difference in snow mold pressure between greens and fairways was the result of the following three factors.

First, the lower height of cut on greens likely doesn’t retain as much moisture in the turf canopy and is less suitable for fungal growth compared to the fairways. Second, the fairways are mostly native soil compared to a sand-based root zone on the greens, which holds more moisture and is usually more conducive to fungal growth. Third, putting greens are more regularly treated with fungicides later into the fall compared to fairways and this could be suppressing early snow mold fungal growth.

The pressure differences can give us some clues about strategies like moisture management and fungicide application timing. These strategies can improve snow mold control on fairways.

What did we learn?

Well, we were reminded that Mother Nature always wins. Sometimes we get a winter like last year, which makes it very difficult to achieve good snow mold control. However, there are some important principles we can focus on moving forward.

First, primer fungicide applications targeting snow mold three to four weeks before your regular snow mold application are a great tool to help suppress early snow mold growth. Second, a mixture of active ingredients from multiple fungicide classes is critical to success.

We’re noticing across many of our research sites that pink snow mold seems to be increasing in severity at the expense of gray and speckled snow mold, so make sure that multiple active ingredients in your mix are strong against pink snow mold.

Lastly, learning from our putting green observations it’s critical to increase drainage and maximize late fall/early spring sunlight. This will increase plant health and make plants more resistant to fungal infections.

To keep learning I also recommend you keep up with our latest snow mold research. Our program posts the results of all of our snow mold research on the Turfgrass Diagnostic Lab research webpage.

This research includes evaluations to find the best products for all types of snow mold under any conditions, our research on the development of the snow mold timing model and other related projects. I encourage you to visit the site to better understand the most effective products and strategies for control. If you have questions, email me.