The thin white line: Snow mold control

Figure 1 Map showing the four University of Wisconsin snow mold research sites in 2017-2018. (Photo: Paul Koch)

Snow mold is one of the primary diseases of golf course turf in Wisconsin, as it is in much of the northern United States. Depending on your location, snow mold can be a disease that costs tens of thousands of dollars to control, with the potential to shut a course down for weeks in the spring without proper fungicide protection.

Or, it might be a disease you spray for because you don’t want that winter to be the one your course receives record snowfall, even though in most years you don’t see much snow mold.

The line between severe snow mold and no snow mold seems to be getting thinner, and the winter of 2017-2018 showed just how sharp the cutoff can be from intense snow mold pressure to almost nonexistent pressure. Knowledge of this cutoff and the impact it has on your risk for snow mold development has important implications for all turfgrass managers in temperate climates.

Wisconsin 2017-2018 results

At Wisconsin, our snow mold investigations include product testing research and applied research investigating application strategies and snow mold fungicide persistence. We typically test at sites across Wisconsin and the upper peninsula of Michigan to provide a broad swath of snow mold pressures, from relatively low pressure in southern Wisconsin to moderate in central Wisconsin and high in northern Wisconsin and the U.P.

Figure 2 Snow mold present following snow melt in 2018 in the non-treated control plots at Cherokee CC in Madison, Wis.; Wausau CC in Wausau, Wis.; Timber Ridge GC in Minocqua, Wis.; and Marquette CC in Marquette, Mich. (Photo: Paul Koch)

In 2017-2018, we conducted snow mold research at Cherokee CC in Madison, Wis.; Wausau CC in Wausau, Wis.; Timber Ridge GC in Minocqua, Wis.; and Marquette CC in Marquette, Mich. (Figure 1). Madison, Wausau and Marquette were product-testing sites, while Minocqua hosted a GCSAA-funded study on optimal snow mold fungicide timing.

In a typical winter, pressure in the non-treated controls would be approximately 25 percent in Madison, 75 percent in Wausau and 90 percent in Minocqua/Marquette. However, recent winters have produced sharper cutoffs, and 2017-2018 was an extreme case: Madison had 0 percent disease in the non-treated areas, Wausau had 11 percent disease, Minocqua had 88 percent disease and Marquette had 99 percent disease (Figure 2). There are just 68 miles between Wausau and Minocqua, an easy one-hour drive up Highway 51… but it made all the difference last winter between intense snow mold and barely any snow mold.

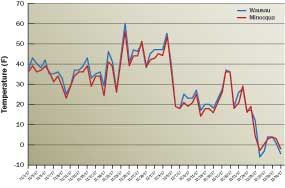

Figure 3 Air temperature during November and December of 2017 at Wausau, Wis. and Minocqua, Wis. (Photo: Paul Koch)

Weather is the major driver in snow mold development, but how did such an intense disease difference develop over such a narrow area? Both Wausau and Minocqua had snow cover from approximately mid-December through mid- to late April, and both sites had similar air temperatures throughout November and December, when snow mold fungal growth is in its early (and crucial) phase (Figure 3). However, Minocqua had 8 to 12 inches of snow on the ground during a deep freeze in late December, while Wausau only had 2 to 4 inches, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Snow Depth Report from Dec. 20, 2017. The deeper snow depth at Minocqua insulated the turf (and the snow mold fungi) below during the cold snap and allowed it to continue growing early in the season. Wausau’s snow depth didn’t provide the same level of insulation and the upper soil froze, inhibiting fungal growth in the same manner as a fungicide application. Though lots more snow fell throughout the winter in Wausau, this early setback was enough to limit snow mold development throughout the entire winter. In general, what happens early in the winter regarding snow mold development is more important than later in the winter because of the time required for these slow-growing fungi to grow and infect turf.

Figure 4 Intense snow mold pressure at Marquette CC provided a strong test of the treatments. (Photo: Paul Koch)

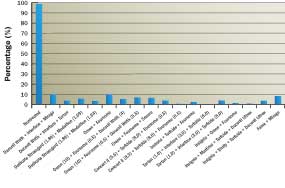

Control under heavy disease pressure

The research trial at Marquette provided an excellent test of the 83 treatments under extreme snow mold conditions. In fact, the snow mold pressure observed at Marquette probably was the highest pressure I observed in the 12 years I have conducted snow mold research at Wisconsin (Figure 4). Not only were the non-treated controls obliterated, treatments with only one or two active ingredients often had levels of disease similar to the non-treated areas. Despite the intense pressure, a surprising 22 out of 83 treatments provided 90 percent disease control or better (Figure 5). An additional 10 treatments provided 80 percent disease control or better, which under the intense pressure observed probably is enough snow mold protection for 90 percent of golf courses in temperate climates.

Nearly all successful treatments in this trial had certain characteristics in common. They all contained at least three active ingredients from different chemical classes, which is important in providing greater knockback of the snow mold fungi in the days and weeks following the application. In addition, nearly all the successful treatments also contained a demethylation inhibitor (DMI) fungicide as one of the active ingredients. DMI fungicides are highly effective against gray and speckled snow mold, so locations that experience extended snowfall and where these snow molds are common should contain a DMI in their mixture.

Treatments that provided greater than 90 percent snow mold control (i.e. less than 10 percent disease) under intense snow mold pressure at Marquette CC during the winter of 2017-2018. Experimental compounds were excluded from this list but can be observed, along with the full report, at https://tdl.wisc.edu/results. (Photo: Paul Koch)

Lastly, most successful treatments also included a contact fungicide (Turfcide 400 (PCNB, AMVAC), Daconil WeatherStik (chlorothalonil, Syngenta), Medallion (fludioxonil, Syngenta), or Secure (fluazinam, Syngenta)). It’s not entirely clear why the contact fungicides are important for snow mold control in heavy pressure, but possible explanations could be broad-based fungal suppression or increased persistence in winter environments relative to other modes of action.

Readers may access the full Marquette report, including pictures of each treatment, at our Turfgrass Diagnostic Lab website in the “Snow Mold Fungicide Trials” section.

Control under lighter disease pressure

The decision to control snow mold and what products to use are relatively straightforward when you know you’re going to experience significant snow mold pressure. However, winters in many locations have become so variable in both temperature and snow cover that many superintendents who spray for snow mold in the southern Great Lakes, southern Midwest and much of the Northeast don’t need to spray at all or can spray fewer products. In fact, we have observed snow mold in the non-treated controls of our southern Wisconsin snow mold locations just twice in the last nine years, and in both cases disease was 20 percent or less.

One thing I’ve learned after 13 years in snow mold research is that superintendents hate to tinker with their snow mold programs. This is understandable because snow mold (unlike many other turf diseases) gives you only one shot to get it right, and it’s a large investment for most clubs. However, most superintendents will agree (and climate data support) that snow depth and duration of cover has become more variable in the past 15 years, and this variability disrupts the growth of snow mold fungi and decreases snow mold severity.

Simply put, I believe most courses outside of the snowiest areas (i.e. lake-effect snow areas, far northern U.S. and the Rocky Mountain West) experience less snow mold pressure today then they did 20 years ago.

Could superintendents still spray four active ingredients on 30 acres of fairways even though they haven’t seen snow mold in 20 years? They could, but they might be able to achieve significant savings without sacrificing disease control by exploring other options.

These other options depend on what kind of pressure exists on the course over multiple years. To measure this, leave an unsprayed area or put down a 4-foot by 4-foot piece of wood prior to spraying as a check plot allowing you to assess disease pressure. Conduct a check plot in multiple winters in approximately the same area to assess differences in snow mold pressure between years. It’s unlikely your course experiences high pressure if you observe disease symptoms taking up less than 10 percent to 15 percent of the non-treated area the following spring, meaning changes to your snow mold program may save you money without a decrease in control.

Options for savings include spraying fewer active ingredients and spraying fewer areas of the golf course. I generally don’t recommend drastically decreasing protection for putting greens, because they are the highest-value areas of the course and typically take up only two to three acres. You may find much larger savings on fairways, and reducing the number of active ingredients being applied to fairways from three to two or two to one can result in significant savings when multiplied over 30 acres. In addition, reserving the highest level of protection (three or more active ingredients) only for areas of the course that tend to see the longest snow cover also can result in significant savings. This might include low swales where snow collects, heavily wooded areas or areas of poor drainage.

These decisions ultimately lie with the superintendent, because any disease that develops is his or her responsibility. However, superintendents looking (or needing) to reduce the amount of money spent controlling snow mold have some potential options based on their location and disease pressure. Test all options on site in a small area of the course prior to widespread implementation to ensure achievement of proper disease control.

Acknowledgements

We’re lucky to have great industry support in our snow mold research, which is not easy because our trials are so large they require us to take up almost an entire fairway. Huge thanks to Craig Moore at Marquette CC, Jay Pritzl at Timber Ridge GC in Minocqua, Randy Slavik at Wausau CC and Eric Leonard at Cherokee CC in Madison for hosting snow mold trials in 2017-2018. In addition, thanks to GCSAA and the Wisconsin Golf Course Superintendents Association for funding the snow mold work investigating proper application timing at Timber Ridge GC. Lastly, thanks to The Andersons, AMVAC, BASF, Bayer, Intelligro, Nufarm, PBI-Gordon, Quali-Pro/Adama, SipcamRotam (now known as Sipcam Agro) and Syngenta for testing products in the trials in Madison, Wausau and Marquette. Our research wouldn’t be possible without their support.