Resistance: Futile or not?

The concept of resistance is not new to the turf industry. Fungicide resistance was first documented in the 1960s and continues to be a major issue in dollar spot and anthracnose populations. Herbicide and insecticide resistance were first reported in the 1970s and now pose a serious threat to our ability to manage certain weeds and insects, such as annual bluegrass (Poa annua), annual bluegrass weevil (ABW) and chinch bugs. In some cases, turf managers are running out of options to control these pests.

Modes of action (MOAs) — how a product works on a molecular level — are prominently displayed on fungicide, herbicide and insecticide labels. Unique MOAs are crucial in the battle against resistance. However, we shouldn’t assume the discovery of new MOAs will outpace the development of resistance. In the last 20 years, only two new fungicide MOAs (QiIs and UOPs), one new insecticide MOA (diamides) and one new herbicide MOA (HPPDs) have entered the turfgrass market. Only one of these, the UOP fungicide fluazinam, has a low risk for resistance. Most discovery work in recent years has focused around succinate dehydrogenase inhibitor (SDHI) and demethylation inhibitor (DMI) fungicides, ALS inhibitor herbicides and diamide insecticides, all of which carry a medium-to-high risk for resistance.

Resistance management is an investment. It often requires more product or more applications than desired to simply attain acceptable control. For pests with a high resistance risk, this investment can pay off in helping preserve the already-limited chemistries we have at our disposal.

Figure 1 A three-way mixture of Barricade 4FL, Princep Liquid and Monument 75WG herbicides applied as an early postemergent application provides excellent control of annual bluegrass and resistance management. Treatments were applied to Tifway bermudagrass Oct. 21, 2015. Photos taken March 9, 2016. Research by Jim Brosnan, Ph.D., University of Tennessee in Knoxville, Tenn. (Photos: Lane Tredway)

What is resistance risk?

Each product is assigned a code associated with its MOA. The resistance risk for the MOAs are determined by the Fungicide Resistance Action Committee, Insecticide Resistance Action Committee and Herbicide Resistance Action Committee. Single-site MOAs — chemistries that prevent a single process or chemical reaction in the pest or pathogen — carry the highest risk for resistance. Each time a single-site chemistry is applied by itself, the population shifts further toward resistance and eventual control failure. In most cases, this process is irreversible. Once a resistant strain becomes dominant in the population, the use of that MOA is lost for the foreseeable future.

Multisite MOAs, which work at more than one site, are valuable tools for resistance management because they carry a low risk for resistance. Tank mixtures of multisite fungicides are particularly useful in helping to prevent or delay resistance. Unfortunately, there are few herbicides or insecticides that classify as multisite.

Pests also vary in their ability to develop resistance. Several high-risk pests mentioned above include anthracnose, dollar spot, Poa annua, ABW and chinch bugs. Determining the resistance risk are factors like how prolifically the pest reproduces, how many generations it completes per year and the amount of genetic variation in its populations. Annual weeds that are prolific seed producers, like Poa annua, carry a much higher resistance risk compared to perennial weeds that spread vegetatively, like dallisgrass. Insects that complete three or more generations per year, like ABW or chinch bugs, are much more likely to develop resistance than Japanese beetles, which only have one generation per year.

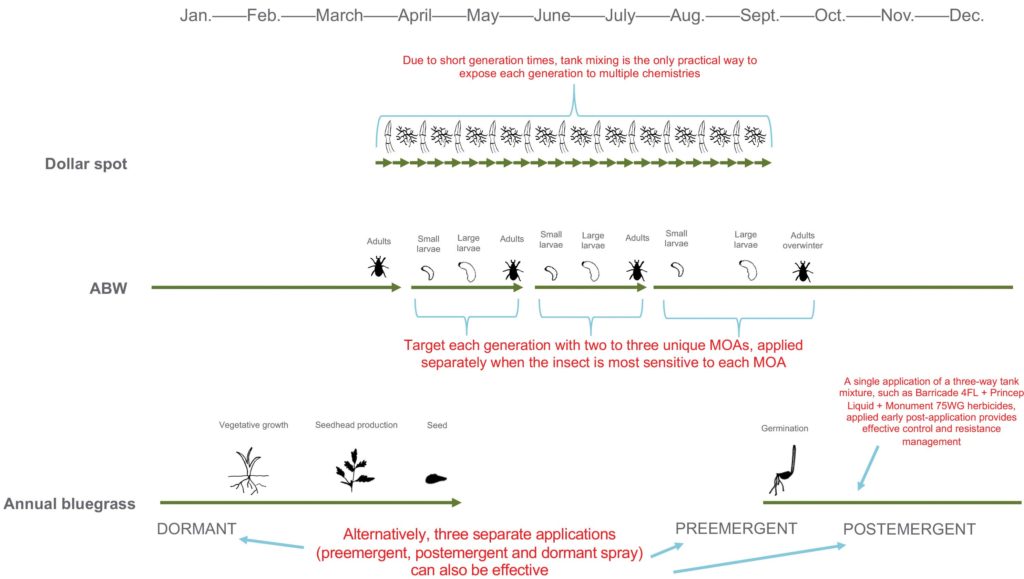

Click to enlarge. | Figure 2 Tank mixtures or rotations can be effective resistance-management strategies, depending on generation time of the target pest. For high-risk pests, each generation of the pest should be exposed to at least two unique MOAs to prevent resistant individuals from increasing in the population. Each arrow indicates a complete generation of the pest. (Graphic: Syngenta)

What’s the best strategy?

The best way to manage resistance has long been debated. Should we tank mix, rotate or keep using the same MOA until it stops working? The reality is there is no one-size-fits-all strategy when it comes to resistance management. Tank mixing can be an effective strategy. Rotation also can be effective. It depends on the resistance risks (both product and pest) and how quickly the pest completes a generation.

Let’s focus on high-risk pests, where the need for effective resistance management is most pressing. For these high-risk pests, we need to treat each generation with at least two unique MOAs, with at least one of the MOAs having a low-to-medium resistance risk. If only high-risk products are available to control a particular pest, we recommend three unique MOAs if possible. Whether or not these MOAs are best deployed in a tank mix or rotation depends mainly on how quickly the pest completes a generation (Figure 2).

Generational approaches to resistance management

The dollar spot pathogen can complete a generation in a matter of hours, so tank mixing is the only practical way to expose each generation to multiple MOAs. Tank mixtures of a medium- or high-risk fungicide with low-risk chemistry, like chlorothalonil or fluazinam, are widely accepted as the most effective way to prevent fungicide resistance. Furthermore, we shouldn’t apply high-risk fungicides like SDHIs back to back, even when tank mixed. We can apply medium-risk products like DMIs twice in succession before rotating to an alternative chemistry. Mixture of a DMI (medium risk) and SDHI (high risk) are only effective where DMI resistance has not yet developed; otherwise the selection of strains with resistance to both chemistries can occur relatively quickly.

ABW completes a generation in four to eight weeks, depending on ambient temperatures. It’s most sensitive to different MOAs at different points in its life cycle, so rotating chemistries targeted to when the insect is most sensitive is a solid resistance management strategy. For example, one could apply a pyrethroid insecticide to control adults, a diamide insecticide to control small larvae inside of the plant and an oxadiazine insecticide to control large larvae outside of the plant. The WeevilTrak blog is found at WeevilTrak.com and includes ABW updates from researchers and features nearly 50 different discussions about resistance.

Poa annua completes only one generation per year in the Transition Zone and South, where it’s a major weed in warm-season grasses. It behaves as a true winter annual in these areas, germinating in the late summer/fall and producing seed in the spring before succumbing to heat stress in the late spring/summer. Just like ABW, different MOAs are most effective against Poa annua at specific points in its life cycle. So, a rotational program can be an effective resistance management strategy. For example, a superintendent may apply preemergent herbicide in August or September, followed by a postemergent herbicide in October or November, and a nonselective herbicide such as glyphosate or diquat in January or February. Another successful strategy is to apply a mixture of three unique MOAs, such as a DNA, PSII inhibitor and ALS inhibitor (Figure 1), as an early postemergent application in October or November.

Pests adapt, and so should we

The high-risk pests discussed earlier are some of the most widespread and economically damaging in the turf industry. Effective resistance management is a worthy investment in ensuring our ability to deliver high-quality turf long into the future. For more information or to download free agronomic programs for your area that can help prevent resistance, manage yearly limits and deliver results, visit GreenCastOnline.com/Programs. The next generation of golf course superintendents will thank you.