One shot to succeed for snow mold control

One of the most important aspects of a superintendent’s job is effectively controlling disease. However, not all turf diseases are created equal. We sometimes observe certain diseases that are not necessarily destructive. Examples include many leaf spots and rusts. Other diseases are more isolated in nature but can be extremely destructive, examples of which are patch diseases like summer patch and take-all patch.

In general, the highly destructive diseases require preventative fungicide applications to provide acceptable control, and the less destructive diseases usually are kept in check with curative applications, if any applications are made at all. Even dollar spot, a highly destructive disease if left untreated, is brought under control if checked early with multiple curative fungicide applications.

The same is not true for snow molds. If budget cuts or a forecast of a warm winter lead the superintendent to reduce the level of snow mold protection, and if the course is unexpectedly buried in snow for months, the superintendent doesn’t have a lot of good options. You can’t go out and spray curatively because the turf is covered in snow.

Do no harm

Trying to remove snow to reduce disease pressure sometimes causes significant damage, as anyone who has tried to remove ice cover is keenly aware. Few sites are as disheartening to northern superintendents as dead turf once snow finally melts in spring, whether it’s from disease or winter injury (Figure 1). Widespread damage results in reduced revenue from lost play, and it almost certainly increases expenses while the turf is nursed back to health, expenses that most maintenance budgets can’t cover without cutting elsewhere.

Figure 1 The budget for this course in central Wisconsin only covers spraying greens and approaches, and the snow mold on the nontreated areas is immense and can take weeks to fully heal.

This concern is why most superintendents in the North “overspray” for snow mold, which in this context is “spraying more fungicide then really is needed.” I’ve talked with numerous superintendents in the southern Great Lakes region — where snow cover rarely sticks around for more than a few weeks — but who still spray two to three active ingredients for snow mold control. I’ve talked with other superintendents who haven’t seen snow mold on their fairways in 15 years but still spray three or more active ingredients to ensure clean turf the following spring.

To be clear, I’m not criticizing those decisions. I think most of them are good decisions based on the expectations and budgets present at their facilities. The agronomic risk associated with underspraying snow mold simply is too great and the economic risk associated with overspraying too low for most northern superintendents to justify significantly reducing their snow mold protection.

Wisconsin research

Choosing the right product, however, doesn’t always mean choosing the most expensive product. A variety of tools are available to assist superintendents in building their snow mold program, including some from several universities that conduct snow mold fungicide research.

Figure 2 This drone photo of the 2016-2017 snow mold trial at Wausau CC shows the immense size of the experimental plot.

Every year, my program at the University of Wisconsin conducts one of the largest snow mold product testing trials in the country. This year, we tested 106 treatments (84 of which are non-experimental compounds) at three sites across the upper Midwest: Cherokee CC in Madison, Wis., Wausau CC in Wausau, Wis., and Marquette CC in Marquette, Mich. (Figure 2). All trials were conducted on fairway-height turf comprised of a mixture of creeping bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera L.) and annual bluegrass (Poa annua L.). Special thanks to superintendents Eric Leonard, Randy Slavik and Craig Moore for hosting trials.

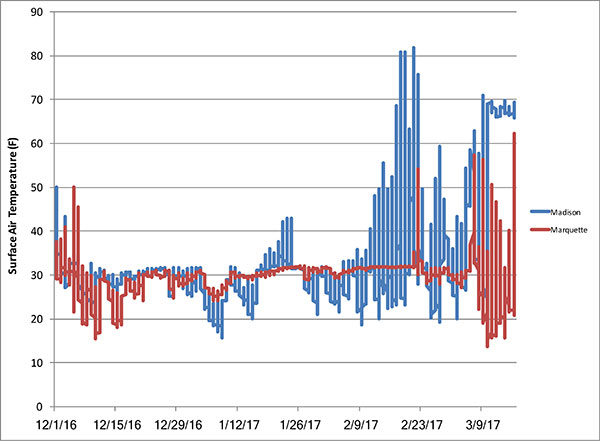

Figure 3 Surface temperature readings provided by Spectrum WatchDog Data Loggers from both the Madison and Marquette sites in 2016-2017. The nearly flat line in Marquette indicates a deep insulating snow cover that is perfect for snow mold development.

The upper Midwest once again had a relatively mild winter that resulted in no snow mold at the Madison site, moderate pink snow mold at the Wausau site and high levels of pink snow mold at the Marquette site.

Speckled snow mold (Typhula ishikariensis) normally is the predominant snow mold present at Marquette CC, and the fact that we saw pink snow mold there this year speaks to the relatively mild conditions. The comparison of surface air temperatures at Madison versus Marquette, as measured by our Spectrum Watchdog Data Loggers, shows that Marquette had a nearly constant surface temperature all of January and February, while Madison’s surface temperature fluctuated wildly (Figure 3). This clearly indicates that Marquette had a deep insulating snow cover during this period that favored snow mold development, while Madison did not.

The trial at Marquette CC had the highest disease pressure, and is the focus of this article, but the full research reports from all three sites, including pictures of each treatment, are available at the University of Wisconsin Turfgrass Fungicide Testing Results webpage. I encourage you to visit the website and view the results in more detail.

The Marquette story

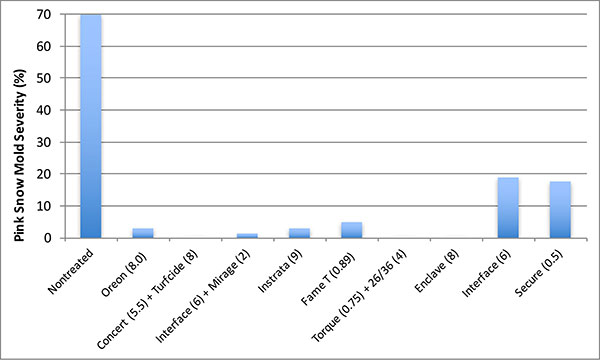

The non-treated control at Marquette CC averaged 70 percent disease over four replications (Figure 4). Despite this high snow mold pressure, 58 of the 106 treatments tested in the trial averaged less than 5 percent snow mold. You may see some treatments that performed best in this trial, and in numerous other trials in recent years, in Figure 5.

Figure 4 Non-treated controls at Marquette CC averaged 70 percent disease, with pink snow mold comprising most of the disease present.

The highest-performing treatments had multiple things in common, but all contained multiple active ingredients from multiple chemical classes. Oreon is a new product from AMVAC, a combination of PCNB and tebuconazole, and can be an effective option for fairway snow mold control. Fame T also is a relatively new product, a mixture of fluoxastrobin and tebuconazole, and has performed well in our trials for two consecutive years. Other treatments in Figure 5 have become “standards,” meaning they have performed at a high level in our trials over multiple sites and multiple years, and have become measuring sticks for new products coming on to the market. These include Instrata (chlorothalonil plus propiconazole plus fludioxonil), Interface (iprodione plus trifloxystrobin) with Mirage (tebuconazole), Concert (propiconazole plus chlorothalonil) with Turfcide (PCNB), Torque (tebuconazole) with 26/36 (iprodione plus thiophanate-methyl), and QP Enclave (chlorothalonil plus iprodione plus thiophanate-methyl plus tebuconazole).

These treatments contain at least two active ingredients, and in most cases three active ingredients (with Enclave having four). However, there also are a disproportionately large number of effective snow mold treatments that contain tebuconazole.

Figure 5 A small subset of the treatments tested at Marquette CC in 2016-2017 and their efficacy against pink snow mold. The full research report, along with treatment pictures, can be accessed at www.tdl.wisc.edu/results.

Of the above treatments, tebu-conazole is included in Oreon, Mirage, Fame T, Torque and Enclave. Tebu-conazole is a demethylation inhibitor (DMI) fungicide, and DMIs in general are highly effective snow mold products. I typically recommend that a DMI of some nature go out in every snow mold application where disease pressure is significant.

But why is tebuconazole included in so many products in place of other DMIs like Banner MAXX (propiconazole) and Trinity (triticonazole)? Our research shows that tebuconazole is not tremendously more effective on snow mold compared with most other DMIs, so my assumption is that tebuconazole gets included more often because of its affordable price. Prices vary wildly depending on numerous factors, but superintendents can often purchase generic tebuconazole for less than $50 an acre — an affordable price for an effective product.

Figure 6 Torque tank-mixed with 26/36 provided excellent snow mold control, but when either product was removed, the control provided dropped dramatically. These pictures are from the 2013-2014 snow mold trial at Wausau CC.

However, even tebuconazole must be mixed with other active ingredients to be effective under intense snow mold pressure. A trial we conducted at Wausau CC in 2014-2105 revealed a useful comparison of Torque combined with 26/36 as well as each product applied alone. Torque applied as a tank mixture with 26/36 provided excellent protection, but when either product was removed, control provided dropped dramatically (Figure 6). We saw this same scenario, where an effective product as a mixture performed poorly on its own, with other effective products like Interface and Secure at Marquette CC this past winter (Figure 5).

The bottom line

Until there are more effective long-term winter forecasting models (get it together, weather researchers) and/or more effective methods for predicting snow mold pathogen activity (get it together, turf pathologists), superintendents are justified to plan for the worst.

Planning for the worst for most northern superintendents entails applications containing two, three or four active ingredients applied shortly before snow cover. Planning for the worst, however, does not necessarily mean spending the most money.

Our research indicates there are numerous effective snow mold treatments available to the superintendent at a range of costs. Peruse the research from Wisconsin and your local university, consult with a local representative you’re familiar with, and find the plan that will provide the snow mold control your club demands at a price that your club can afford.

Paul Koch, Ph.D., is an assistant professor in the Department of Plant Pathology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Please call (608-262-6531) or email Paul (plkoch@wisc.edu) with questions, comments or concerns.

Photos by: Paul Koch, EPIC Creative