Mistakes Happen: Part Dew

In the October Golfdom I wrote about several product application mistakes that superintendents potentially can make. These mistakes included an overdose of plant growth regulators, products used to correct said overdose, high rates of foliar fertilizer, and the dreaded issues caused by bug repellant sprayed on turf (I can see a perfect size 10 Footjoy on your tee now). If you know me, you know I have many more turf-related mistakes to discuss. So here we go again.

Mistakes often happen because we become too familiar or comfortable with the products we use. This can cause us to become complacent and take for granted subtle differences between products.

A good example from my checkered past: I had been using the original granular formulation of azoxystrobin for years at a rate of 0.40 oz. /1000 ft2. Several years later I purchased a new liquid formulation. When it came time to apply the new formulation I went into autopilot during the mixing process. Several days after the application I began to notice some unusual disease patterns on my greens. I became confused because I had just applied a great active ingredient only a few days prior.

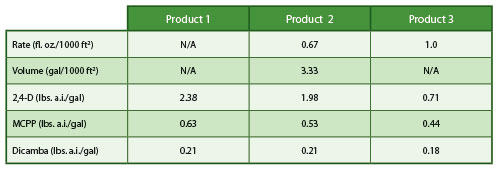

FIGURE 1:

Three-way combination active ingredients and percentages used in this demonstration trial.

Upon investigation I realized I had applied the 0.40 oz. /1000 ft2 rate called for with the original granular formulation. However, I actually needed 2.0 fl. oz. /1000 ft2 of the new liquid product. Needless to say, I was quickly back on the sprayer.

Mistakes like this happen when we go too fast, don’t stop to think about the product we are using, and fail to read the label one more time. Here I highlight three additional mistakes from the 19 different demonstration treatments that were conducted at the Turfgrass Research, Outreach and Education Center, University of Minnesota, St. Paul, Minn. These include issues arising from a herbicide application, fertilizing incorrectly and against label recommendations, and applying a high rate of mineral oil. All “mistakes” were applied to a V-8 creeping bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera L.) putting green mowed at 0.125 inches six days a week.

Mistake No. 1

The most commonly used post-emergent broadleaf herbicide on the market is a three-way combination of 2,4-D, MCPP (mecoprop) and dicamba. It’s an extremely effective and economical combination on many broadleaf weeds. However, this three-way combination product produces an issue because of the sensitivity that creeping bentgrass, especially at greens height, has to 2,4-D.

2,4-D is a good active ingredient on many broadleaf weeds, especially dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) and broadleaf plantain (Plantago major), but it’s not recommended to apply broadcast applications of 2,4-D alone to creeping bentgrass greens. Spot treatments may be feasible, but injury may still occur with misapplication.

MCPP formulated alone is specifically marketed for use on creeping bentgrass putting greens. It has a higher degree of safety on creeping bentgrass and is effective on white clover (Trifolium repens), for which 2,4-D provides marginal control.

TABLE 1:

Three different three-way combinations of 2,4-D, MCPP and dicamba and their differences for use on creeping bentgrass putting greens.

Dicamba also is formulated alone and labeled for creeping bentgrass, although the product makers give no direction for use on putting greens, and the label indicates injury may occur at rates higher than 0.50 lb. a.i./acre. Dicamba will provide good control of prostrate knotweed (Polygonum aviculare), which 2,4-D and MCPP have trouble controlling.

Aside from 2,4-D being injurious to creeping bentgrass, other issues with three-way combinations of 2,4-D, MCPP and dicamba come up because there are many different formulations that may or may not have restrictions for use on creeping bentgrass putting greens.

The confusion is compounded more by the use of the same brand name for different formulations. Many products include 2,4-D, MCPP and dicamba, but all have different restrictions and/or rates for use on creeping bentgrass putting greens (Table 1). There are, however, three-way combinations of 2,4-D, MCPP and dicamba specifically designed for use on creeping bentgrass, even at greens height. Close inspection of the label will show a reduction in the amount of 2,4-D these products contain, often a reduced application rate when used on greens, and even different application volumes for some products. All products warn against overdosing bentgrasses to avoid injury.

The confusion is compounded more by the use of the same brand name for different formulations. Many products include 2,4-D, MCPP and dicamba, but all have different restrictions and/or rates for use on creeping bentgrass putting greens (Table 1). There are, however, three-way combinations of 2,4-D, MCPP and dicamba specifically designed for use on creeping bentgrass, even at greens height. Close inspection of the label will show a reduction in the amount of 2,4-D these products contain, often a reduced application rate when used on greens, and even different application volumes for some products. All products warn against overdosing bentgrasses to avoid injury.

I applied the most economical three-way product available containing 2,4-D, MCPP and dicamba (Figure 1) at the high rate, which is not labeled for creeping bentgrass putting greens. Yellowing occurred within three days after application and was highly evident by seven days after application (Photo 1). Yellowing was still evident at three weeks after application (Photo 2).

If this mistake is identified at application it may be possible to wash the product off with irrigation because 2,4-D is mostly foliar absorbed. If this is not the case, the damage has been done as the product is already in the plant. A nitrogen and iron application may allow the plant to grow out of the product and may mask some injury symptoms, but do not expect miracles.

As many of us know, paint and pigments are popular and can help in this situation, or at the very least make you feel better. The product I applied should not kill turf under label recommendations, but it will be a setback for at least three to four weeks after application. Communication to the appropriate individuals is key to explaining the mistake and expected recovery.

As many of us know, paint and pigments are popular and can help in this situation, or at the very least make you feel better. The product I applied should not kill turf under label recommendations, but it will be a setback for at least three to four weeks after application. Communication to the appropriate individuals is key to explaining the mistake and expected recovery.

Mistake No. 2

It’s easy to take fertilizer applications for granted. You look at the analysis, decide how much to apply and head on out, assuming you calibrated, of course. However, even though you may have purchased a product with the same analysis, manufacturing processes can alter the size guide number (SGN) of the product slightly. That happened to me, and a leopard look on my greens was the result (Photo 3).

We don’t often think about a fertilizer application in terms other than the rate. However, I’m starting to see more fertilizer products bearing label cautions regarding what you should and shouldn’t do.

We don’t often think about a fertilizer application in terms other than the rate. However, I’m starting to see more fertilizer products bearing label cautions regarding what you should and shouldn’t do.

One such caution causing superintendents trouble is, “Do not apply to wet foliage.” This is interesting because so many of our applications happen in the morning, and dew creates wet foliage. This causes fertilizer to stick to the plant. The fertilizer then begins pulling water out of the plant, causing desiccation and damage.

Some fertilizers do this so quickly that you will even see statements cautioning that watering after application to wet foliage may not help prevent damage. Even though mowing may remove much of the dew, it can continue to collect even after mowing and before the applicator gets to that green.

In this trial the product was applied early in the morning at the high label rate of 1.0 lb. nitrogen /1000 ft2 to turf that had a high amount of dew on the foliage. The product was watered 1 hour later with 0.20 inches. I did this treatment because a few years ago a colleague of mine suffered severe foliar damage with this exact application.

In this trial the product was applied early in the morning at the high label rate of 1.0 lb. nitrogen /1000 ft2 to turf that had a high amount of dew on the foliage. The product was watered 1 hour later with 0.20 inches. I did this treatment because a few years ago a colleague of mine suffered severe foliar damage with this exact application.

My replication was not as successful this time around. I did not see any of the foliar “staining” and leaf blight damage that happened to a fellow superintendent (Photo 4).

Unfortunately, if you are on the wrong side of this situation there’s nothing you can do quickly to minimize damage. The hope here is that you applied the correct rate, in which case the turf should grow out of the damage soon enough.

Mistake No. 3

Have you ever been on a sprayer so long that on the drive home you are still paying attention to the “phantom booms” on the back of your vehicle? It happens to me all the time. We can get too comfortable with our rigs, which causes complacency.

Many of the products we use can have detrimental effects when applied with too much overlap. Many now contain pigments that help us see what we are spraying, but also provide an opportunity for us to go on autopilot because we have the “tracer.” I always pay more attention when I don’t use an indicator dye.

Many of the products we use can have detrimental effects when applied with too much overlap. Many now contain pigments that help us see what we are spraying, but also provide an opportunity for us to go on autopilot because we have the “tracer.” I always pay more attention when I don’t use an indicator dye.

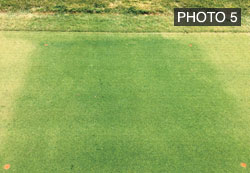

In this demonstration I applied a combo product containing a pigment and a mineral oil at twice the high rate to simulate a spray overlap (also note this high rate was for a snow mold application, which should not be used in the summer). The label clearly warns to not “over-spray” or “double-spray.”

At two weeks after application the plot areas looked great. There was still a noticeable color difference because of the pigment, and the luster provided by the mineral oil was visible, but there were no issues with turf quality (Photo 5). By three weeks after application the pigment began to fade, as did the look and feel of the mineral oil, but the plots still looked good (Photo 6).

Although there were no issues with this application, this type of application in more stressful weather conditions may show different results. It also may be difficult to quickly remedy this situation as the product will be hard to wash off after the application has dried and does not quickly mow off, which was seen in this trial.

Although there were no issues with this application, this type of application in more stressful weather conditions may show different results. It also may be difficult to quickly remedy this situation as the product will be hard to wash off after the application has dried and does not quickly mow off, which was seen in this trial.

Keeping stress low is your biggest asset with an application like this, as it slowly gets removed from the plant. If you are lucky enough to have a GPS-guided spray rig you may disregard mistake No. 3 — and I’m jealous.

Managing Mistakes

As I mentioned in the previous article, many a superintendent mistake revolves around the products we use. However, comfort and complacency play big rolls. Taking for granted that products don’t and will not change can quickly slap you out of your comfort zone. Labels and products can change quickly without you knowing it by virtue of the fact that there is just a better formulation available for a product you think you’re familiar with. New product regulations may stipulate changes to applications or may have completely changed formulations. You may even find yourself reading a product label you’ve been using for years and notice something new, like “Do not apply in the drip line of trees,” which came to the forefront a few years back but has been on most broadleaf herbicide labels since day one.

Getting too comfortable with the equipment you use, not paying attention and thinking you can do two things at once can quickly come back and haunt you.

Photos Courtesy: Matt Cavanaugh