Dr. basidiomycetes or: How I learned to stop fairy ring

Fairy ring symptoms observed on greens, tees, fairways and roughs are not caused by magical faeries, but we have to blame someone or something for the destructive nature of this disease complex (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Classic example of fairy ring on a putting green.

Visual fairy ring symptoms appear in peculiar shapes of circles or rings or semi-circles as either severely wilted and necrotic turf (Type I), dark green and lush growing turf (Type II) or mushrooms or puffballs (Type III) that can literally pop up overnight along the affected outer edges (Figures 2, 3, 4). Those three visual categories or types of fairy ring symptoms occur alone or together (Figure 5). With fairy ring-affected turf sites, the root zone often becomes hydrophobic or water repellent, which is not good when trying to keep roots alive and functioning during a long, hot summer.

Figure 2: The meadow mushroom, Agaricus campestris, often found on fairways and roughs.

Figure 3: Close-up of the common meadow mushroom, Agaricus campestris, often found on fairways and roughs.

Figure 4: Good example of a “puffball” in higher height of cut turf, although this fairy ring species can be a problem in greens and tees, especially those with sand root zones.

Figure 5: Good example of Type I fairy ring symptoms (necrotic, dead turf zone) with Type III symptoms (mushrooms along the outer edge), and Type II symptoms (slightly darker green, stimulated turf along the inner edge).

Figure 6: Fairy ring in bermudagrass green with aeration and sand topdressing to help recovery.

Managing root zone moisture and organic matter has become an important best management practice for maintaining healthy turf and minimizing the occurrence and impact of fairy ring.

Prolonged periods of hot weather and no rain in the summer often trigger the appearance of fairy ring. Circles or arcs of wilted, necrotic and nearly dead turfgrass can appear quickly. A soil surfactant program — initiated in the spring and ideally continued into the summer and fall — is a good way to alleviate the wet/dry roller coaster and facilitate some consistent, uniform soil moisture.

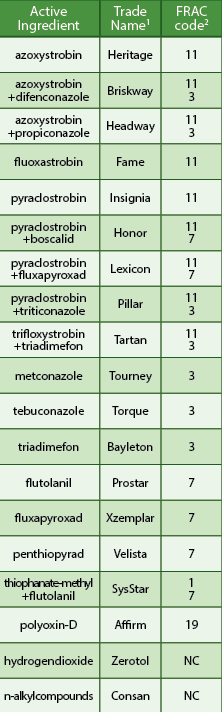

Fungicide applications can be useful for managing fairy ring, but there’s much more involved than just squirting the product. Back in the 1990s, the only fungicide labeled for fairy ring was Prostar (flutolanil, Bayer Environmental Science). Today we have many options (Table 1).

Table 1: Fungicide products currently labeled — or pursuing a label — for fairy ring management in turf. Please read the label carefully for application rates and water-carrier volumes recommended by the manufacturer, application timing, post-application irrigation instructions, tank-mix options with soil surfactants/wetting agents and other detailed instructions. Note, some products listed may not have a federal label but may be used in accordance with manufacturer-issued 2 (ee) recommendations. Also, there are other adjuvant and soil amendment-type products available that provide recommendations for fairy ring-control programs

A preventive fungicide program can work — in theory — if we could somehow predict when and where fairy ring will occur. Fairy ring seems to show up on a green or a fairway in one year but not the next, or on a few greens, but not all greens. Even so, some fungicide products have instructions for making preventive applications, and many superintendents have had success with preventive programs while others have had challenges “dialing in” the optimum timing for a preventive program that works at their location. One preventive application may not be enough to provide season-long control.

We use a curative method in many cases because that’s when we actually can see fairy ring symptoms, so we know exactly where to target our control efforts. A good curative approach starts with punching holes and venting the root zone, followed-by a soil surfactant and fungicide applications that’s watered in. Then use your agronomic skills to “rescue and recover” the turf (Figure 6).

Fairy ring management requires a multi-faceted approach that uses your knowledge and expertise in plant pathology, soils, agronomy, weather forecasting and persistence.

Fairy ring can be ferocious in Florida

John Cisar, Ph.D., retired from the University of Florida but now is active in consulting and research, says fairy ring season on Florida golf courses is all year — during the dry season, wet season and in between. Timing preventive fungicide applications can be as mystifying as timing the stock market. It’s difficult in south Florida to base applications on the 55-degree to 60-degree soil temperature threshold because soil temperatures rarely get low enough. Fairy ring symptoms often appear after spring aeration, and severe symptoms are often stimulated by those wet/dry (rain/drought) cycles that occur within a season. So what to do?

Know your fairy ring symptoms. Dark green rings of stimulated turf, or circles of necrotic/dead turf? Mushrooms or puffballs present? When does fairy ring occur? Do you see fungal mycelium in the thatch or in the soil root zone? Have you done an incubation bioassay to determine root zone depth? This will let you know where to target a fungicide. Basically, remove a cup cutter-sized plug, or even several soil probe-sized plugs, place them inside a large plastic bag with a moist paper towel, sit them on a bench top for one or two days and see if any whitish, thick cottony mycelium appears, and specifically where — at the thatch/soil interface or lower in the root zone. This will give you an indication of where to target your product applications.

Know your management. Does the turf look “hungry?” Have your soils become hydrophobic? Are you routinely applying surfactants or wetting agents to manage soil moisture uniformity? Do you use those products to retain water or increase permeability of water?

Plan your attack. Whether you are using soil temperature or past history or intuition, apply a preventive product in advance of historical occurrences at your site. With either preventive or curative applications, expand treated areas beyond previous or current fairy ring-affected areas to account for the fungus continuing to grow and spread. One preventive or curative fungicide application probably is not enough to keep the fairy ring fungus in check in Florida, so repeat applications are needed. Also, water in the fungicide after application with at least a quarter inch of irrigation or enough water to “rinse in” the product. Use a soil surfactant either before or with the fungicide application, and water in the surfactant, too. Check the fungicide label to follow any special instructions with wetting agents/soil surfactants and post-application irrigation.

Reapplying a fungicide at about a 30-day interval (or as instructed on the product label), as well as prudent cultural practices to help recovery, is necessary on seashore paspalum in Florida because it usually takes longer to heal in those dead zones.

Photos by John Cisar.

Mike Fidanza, Ph.D., is a professor of plant and soil sciences at The Pennsylvania State University, Berks Campus, Reading, Pa. You may reach Mike at maf100@psu.edu or on Twitter: @MikeFidanza for more information.