Buffalograss can stand the heat, drought

By Keenan Amundsen, Ph.D.

Drought, regulatory restrictions, limited resources, implementation of conscientious efforts to save water, and the appeal of reduced irrigation costs are some of the factors driving the turfgrass industry toward reduced irrigation input. The use of species that have improved water use efficiency, and drought tolerance, or that require less water for normal growth and function than traditional turfgrasses, is a viable choice for superintendents wanting to conserve water. Turfgrass species such as buffalograss that are naturally adapted to and actually thrive in arid environments have a competitive advantage when grown with less water compared to many traditional species from more temperate and humid regions.

Buffalograss experimental lines growing near Mead, Neb., evaluated for late-fall color retention. This image was taken on October 29th, 2012. Photo: Keenan Amundsen, Ph.D.

Buffalograss is found naturally growing throughout the Great Plains region of North America. It is a warm-season, perennial, stoloniferous species that forms a dense sod and has a dark green color and fine leaf texture. The turfgrass breeding program at the University of Nebraska has focused on developing improved turf-type buffalograss cultivars since entering into a partnership with the United States Golf Association in the mid-1980s. Over the past several decades, the research focus was to improve low-mowing tolerance, enhance wear tolerance, increase canopy density, accelerate establishment rate and develop management practices for optimal buffalograss performance. This research has led to the development of several commercially available turf-type seeded and vegetative buffalograss cultivars.

Two of the best attributes of buffalograss relative to water conservation are low temperature and drought tolerance. Buffalograss is a warm season species that can be found naturally occurring in turf stands extending northward into Canada. Buffalograss has a strong winter dormancy response, which helps it survive seasonal low temperatures in northern climates. Once dormant, most buffalograss varieties exhibit a straw color appearance, often considered a drawback of the species.

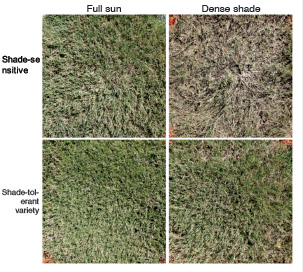

Buffalograss shade-tolerant and shade-sensitive experimental lines grown in full sun and under a shade cloth blocking 60% of the natural light (dense shade). The images were taken following three years of light treatments. Photo: Keenan Amundsen, Ph.D.

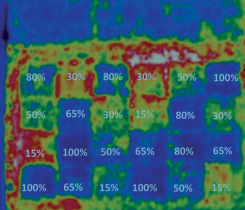

The breeding program at the University of Nebraska is focused on identifying and breeding for buffalograss lines with an extended growing season, or that have improved color retention into the dormancy period and are less prone to winter injury (Figure 1). Dormant buffalograss can be an advantage in terms of water use, since it is not actively growing when dormant and needs little moisture. Additionally, actively growing buffalograss has an expansive root system that allows it to use more of the available soil moisture compared to many other turfgrasses, resulting in less supplemental irrigation.

Challenges to more widespread use of buffalograss arise, in part, from limited seed/propagule supply due to increased demand for native turfgrasses throughout the United States, perceived poor establishment concerns and poor shade tolerance. New cultivars are being developed to address each of these issues. For example, buffalograss is often considered to be intolerant of shade. A three-year study was used to successfully identify selections that maintain an acceptable level of performance in the shade (Figure 2). The commercially available vegetative variety, “Prestige,” was among the best for shade tolerance. Increased production is being addressed through basic research to overcome mechanisms of seed dormancy, improve seed yield, enhance sod production characteristics and identify sources of resistance to common buffalograss diseases. These traits will help lower end-user costs, increase production and reduce management costs.

A common misconception of buffalograss is that it is a “no maintenance” species. This concept often creates problems during establishment. Proper establishment is the single largest factor impacting long-term success or failure of a buffalograss stand. Like any other turf species, buffalograss seeds, plugs and sod require more intensive management during the establishment period and can be significantly reduced once established.

Seasonal comparison of adjacent buffalograss and tall fescue turf stands growing near Mead, Neb. Photo: Keenan Amundsen, Ph.D.

A mature buffalograss stand will survive in areas where it is well adapted with minimal inputs, however a high-quality turf stand can only be achieved if fertility, irrigation, mowing and other cultural practices — including weed control — are applied. When grown in a golf course setting, current buffalograss varieties are most suited to the rough or areas managed at a higher height of cut. A high-quality buffalograss stand can be maintained with as little as 1.5 lbs. N per 1,000 sq. ft. per year and 0.25” of water per week either through rain or supplemental irrigation per growing season. Most buffalograss cultivars have an optimal mowing height of 2 to 3 inches, but low mowing-tolerant varieties can be maintained at 1 inch. Additionally, buffalograss can be left unmown to achieve a native prairie look.

Buffalograss offers color, texture and other differences relative to many other turfgrass species. When grown adjacent to cool-season grasses, buffalograss offers a contrast during the late spring and early fall, when both species are actively growing; during the heat of the summer, when buffalograss thrives; or in the late fall/early spring, when cool-season species are actively growing (Figure 3). With a well-planned design, buffalograss could be incorporated as an architectural feature of a course, offering a target for strategic shot placement while adding to the overall aesthetics of the course.

The current and projected turf management perspective for the game of golf is well aligned with the use of a grass species that favorably responds to reduced inputs. Buffalograss offers the superintendent a viable option for sustainable management practices, greatly improved resource conservation and aesthetic appeal and playability.

Acknowledgment

I would like to thank the United States Golf Association for providing financial support for this project.

Keenan Amundsen is an assistant professor of turfgrass breeding at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Keenan can be reached at kamundsen2@unl.edu.