Bermudagrass adaptability in northern climates

Superintendents always look for ways to increase playability and durability of turfgrass stands, particularly under periods of stress. They often achieve this by selecting a species or a group of species for a specific climatic zone (i.e. warm-season grasses in the South and cool-season grasses in the North). This works well if the golf course has a grass that performs well for much of the year.

Superintendents always look for ways to increase playability and durability of turfgrass stands, particularly under periods of stress. They often achieve this by selecting a species or a group of species for a specific climatic zone (i.e. warm-season grasses in the South and cool-season grasses in the North). This works well if the golf course has a grass that performs well for much of the year.

However, there still are growing season periods when stressful climatic conditions affect turf quality. To minimize this, golf course managers in the Transition Zone have used a combination of both warm- and cool-season grasses through overseeding programs. This can work well, but it can also affect turf quality during the transition periods.

With the advancement of cold tolerance and winter hardiness in common and hybrid bermudagrasses over the past 15 years, we have proposed using both warm- and cool-season grasses independently on the golf course. So, on northern golf courses we proposed dedicating areas of the course to warm-season grass (bermudagrass) during the year when it performs best. Consequently, this approach should allow recovery time for cool-season turf areas during these same periods. This allows courses to survive the stressful summer months with little or no play.

Can a golf course dedicate a significant section of its driving range, tees or tees on par-3 holes or others to bermudagrass with the idea of utilizing it during July and August, when it performs best? The answer to that question lies in whether those bermudagrass areas can be sustainable from year to year without a significant increase in maintenance.

In conjunction with the USGA Green Section, we established a study designed to determine if different cultural practices can provide enhanced cold tolerance to four winter-hardy bermudagrass cultivars grown at the northern limit of bermudagrass adaptation.

Study Methods

Figure 1 Establishment of bermudagrass research plots at the Ohio Turfgrass Foundation Research and Education Center in April 2014.

The study was initiated in April 2014 on a sand-based area at the Ohio Turfgrass Foundation Research and Education Facility, Columbus, Ohio (Figure 1). Four cold-tolerant cultivars of bermudagrass (Latitude 36, Riviera, Patriot and Northbridge) were established by sod while still dormant. Latitude 36 and Riviera were grown at the research facility and were harvested and transplanted. Patriot and Northbridge were provided by a sod farm in Delmar, Md. Treatments were applied and data were collected during the fall of 2014 and reported to the USGA Green Section. In the spring of 2015, all bermudagrass cultivars suffered virtually 100-percent winterkill. The study was reestablished June 1 for fall treatments. It was determined that sprigging would be the best method of establishment. The plots were sprigged on July 14 and mowing began Aug. 3.

The plots were mowed five times per week at 0.75 inches. In the spring, we used foramsulfuron (Revolver) to control annual grassy weeds and overseeded ryegrass (from samples received for the sod farm) at a rate of 0.4 fl. oz./1,000 sq. ft. During the growing season, the bermudagrass received 0.5 lb. of nitrogen/1,000 sq. ft. (ammonium sulfate) weekly and were sand topdressed and dethatched every two weeks.

We replicated treatments three times and used a split-plot design. The main plot factor was bermudagrass cultivar and the subplot factor was cultural practice. We initiated cultural treatments Sept. 1 and continued until all plots were dormant each fall. The cultural treatments consisted of:

- Untreated control

- Turf colorant at a rate of 16 fl. oz./1,000 sq. ft. every 14 days

- Trinexapac-ethyl at a rate of 0.125 fl. oz./1,000 sq. ft. every 14 days

- Trinexapac-ethyl at a rate of 0.375 fl. oz./1,000 sq. ft. every 14 days

- Turf colorant at a rate of 16 fl. oz./1,000 sq. ft. plus trinexapac-ethyl at a rate of 0.125 fl. oz./1,000 sq. ft. every 14 days.

- Turf colorant at a rate of 16 fl. oz./1,000 sq. ft. plus trinexapac-ethyl at a rate of 0.375 fl. oz./1,000 sq. ft. every 14 days.

We used no covers during the fall or winter of 2014. Because of the significance of the winterkill during the study’s first winter, we installed covers on the plots daily during the fall of 2015 when the forecasted overnight low was less than 50 degrees F. The covers were left on for the entire winter.

Results

Figure 2 Color differences between the covered study and uncovered surround.

There were dramatic differences in spring green-up among treatments from year to year. We saw virtually 100-percent winterkill after the first winter and no observed difference in spring green-up after the second winter. We speculate that this was due to the vastly different weather patterns of the two winters and the decision to use winter covers during the second year (Figure 2).

Figure 3 Research plots demonstrating fall color retention in October 2015.

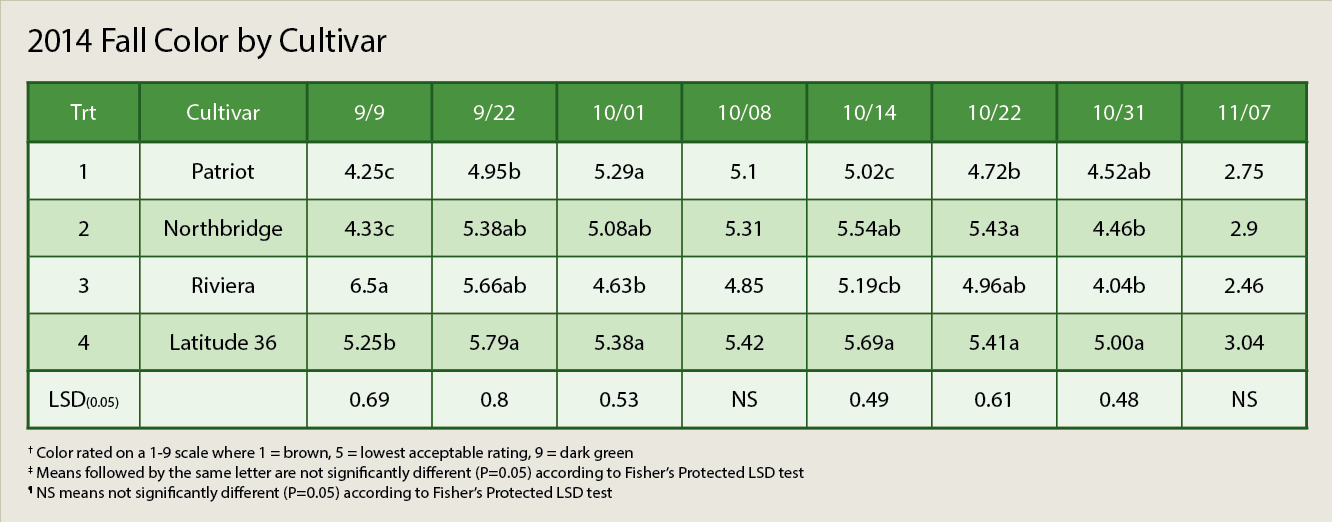

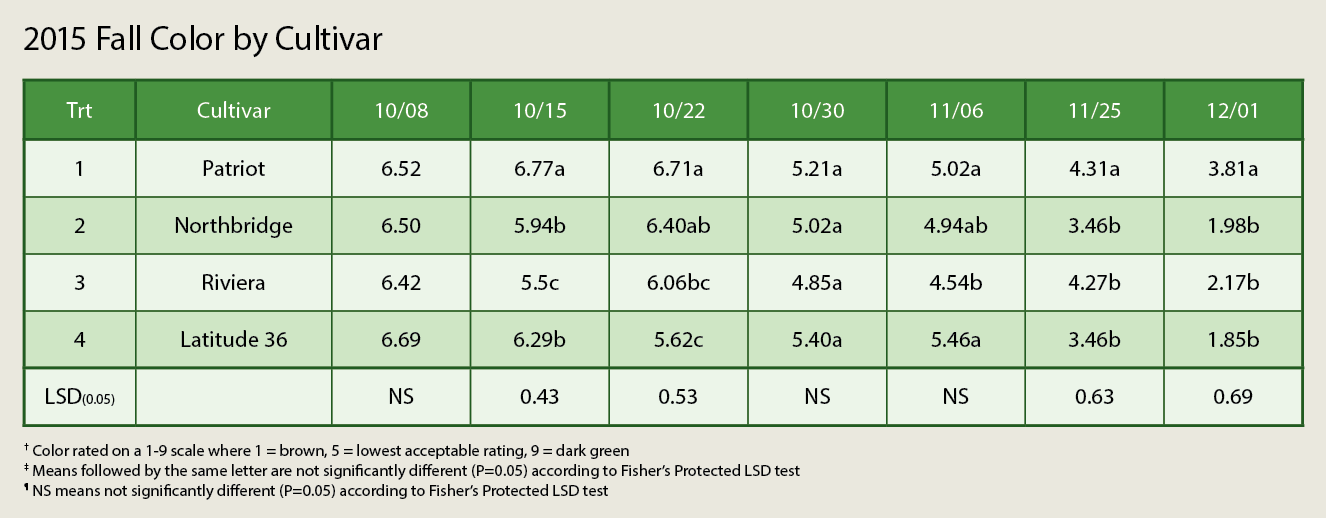

We observed acceptable color ratings (greater than 5) through mid-October in both years for all cultivars (Figure 3). Generally, the hybrid bermudagrasses (Latitude 36, Patriot and Northbridge) outperformed the common variety (Riviera) (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1

Table 2

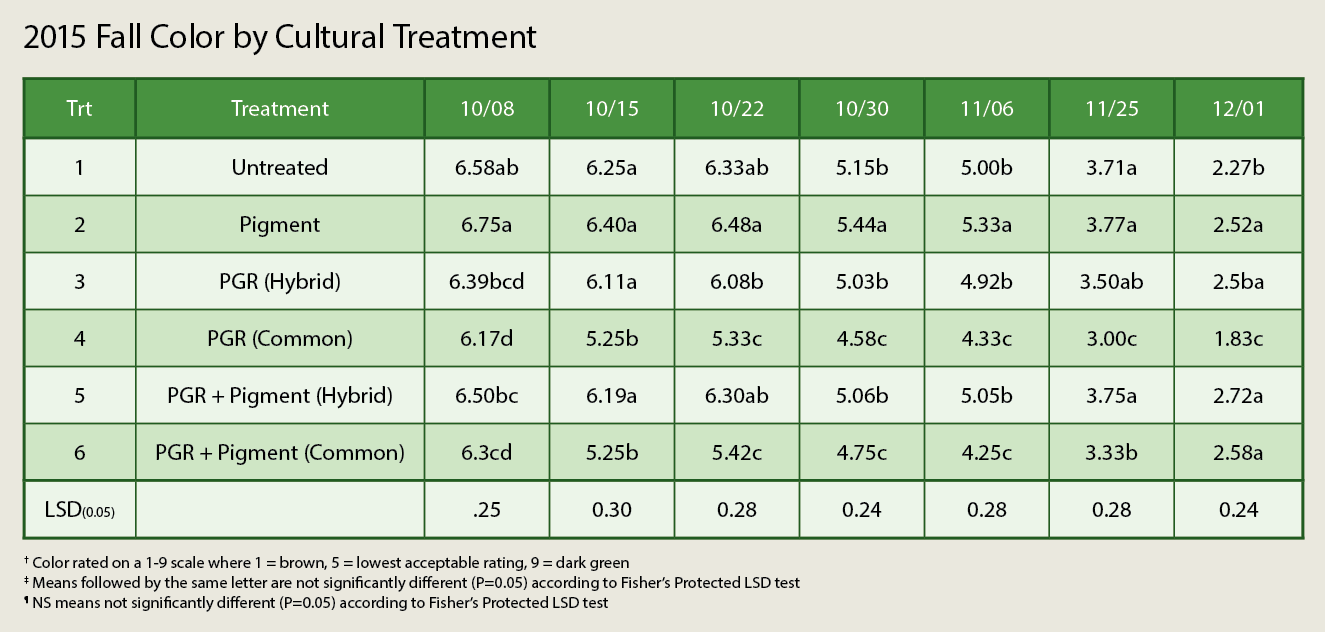

Treatments that included pigments produced both observed and statistical differences in fall color ratings. (Table 3)

Table 3

There were no observed differences of soil temperature, canopy temperature or divot recovery between treatments or cultivars throughout the duration of the trial.

More questions than solutions

As occurs many times with research, you sometimes come up with more questions than solutions. We discovered challenges to growing bermudagrass in northern climates. Some of these challenges are beyond our control. This was demonstrated in the loss of the plots during the first year of the trial.

The 2014-2015 winter was one of the colder winters in Ohio in some time. This trial was designed to determine if the winter-hardy bermudagrass varieties along with cultural practices (pigments and PGR) could survive Ohio winters. After much discussion, we initially decided against using winter covers as they were considered an additional input that wouldn’t be needed on a similar cool-season turf. However, we decided to use covers in the spring of 2015 to protect against losing the plots in two consecutive years.

Subsequently, the winter of 2015-2016 was extremely mild, and covers may have mitigated any differences that may have been observed without them. This trial was performed on a 100-percent sand root zone. We have plans to conduct a similar trial on finer-textured soil and compare the differences to this trial.

The cold-tolerant bermudagrasses in this trial maintained acceptable color ratings well into October in both years. This is well past the July-August window that we proposed using the turf as an active teeing area on the golf course.

There were no differences in fall divot recovery between variety and treatment. However, an average of 70-percent divot recovery occurred by Nov. 1 on divots that were created on Sept. 1 across all cultivars.

There is work to be done to ensure that bermudagrass can be managed sustainably from year to year on a golf course in a northern climate. We believe it is worth further research because of the potential benefits it could provide during the hot summer months, when it has the potential to outperform cool-season grasses under the same conditions.

Matt Williams, an M.S. candidate, is a program coordinator for the Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center at The Ohio State University, David S. Gardner, Ph.D., is an associate professor of Turfgrass Science at Ohio State, and John R. Street Ph.D., is a professor emeritus of Turfgrass Science at Ohio State. You can reach Dave Gardner at gardner.254@osu.edu for more information.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Pamela Sherratt, M.S., Dominic Patrella, Karl Danneberger, Ph.D., Keith Happ, the USGA Green Section, the Ohio Turfgrass Foundation and Oakwood Sod Farms for their support on this project.

Photos: Matt Williams