Annual bluegrass control in golf turf

Spring is a wonderful time of year for superintendents. Grass growing conditions are often excellent, temperatures are moderate, heat and drought stress are usually absent, and golfers are just happy to be playing. However, there is one problem that annually disrupts a superintendent’s spring: Poa annua. Whether dying from ice damage or producing copious quantities of seedheads, Poa annua remains a grass (or weed) that most superintendents wish they didn’t have to see.

Figure 1: When Velocity is applied frequently, selective control is achieved, but creeping bentgrass can be severely injured and significant voids can occur as the Poa annua dies. Photo: Velocity

I’ve been working on Poa annua control for nearly 30 years and clearly haven’t had much success. Controlling Poa annua isn’t really the problem. Rather, control must occur slowly so that turf quality is not reduced—and that’s not how most herbicides work. Also, there must be enough safety so the desired turf species shows no injury. Many superintendents have experimented with low rates of Roundup (glyphosate), high rates of iron, microbial products, etc. Yet, we still have lots of Poa annua on our golf courses.

There always is a new herbicide that will solve the Poa annua problem once and for all, right? Well, don’t bet on it. My 30 years of experience have taught me that Poa annua is a wily and tenacious competitor and no single herbicide will defeat it. It will take multiple chemistries, an equally tenacious superintendent and some luck to have a golf course with little to no Poa annua. It can be done, and I’ve seen it done, but it takes consistent and persistent effort.

Poa annua biology

What makes Poa annua such a difficult weed to control? To paraphrase President Clinton, “it’s the seed, stupid.” Poa annua is so competitive because it produces tremendous amounts of viable seed at any mowing height. Further, its ecological niche is extremely well suited to the golf course environment. Frequent irrigation is perhaps the biggest contributor to Poa annua establishment.

When you do find an herbicide that combats it, Poa annua seed most likely will repopulate the voids left by the dying Poa annua. In the scenario where an herbicide actually kills Poa annua, the turf manager is so anxious to get grass back on the golf course that further thoughts of controlling Poa annua are quickly forgotten. The Poa annua comes back from seed along with other desired grasses, such as creeping bentgrass.

While data are a little hard to come by, Calhoun (2010) suggested that Poa annua seed can be viable up to 6 years in the soil. Several authors have determined that the large percentage of Poa annua seed shed by Poa annua plants will germinate in the first year following production. To net this out, if you can eliminate Poa annua from your turf and continue to eliminate it before more seed is produced, then after +/- six years, the Poa annua seed bank will be much reduced and the Poa annua problem will be much easier to manage.

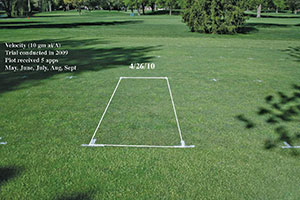

Figure 2: When Velocity is applied regularly but infrequently, in this case five monthly applications at 2 ounces product per acre in 2009, gradual but significant reductions in Poa annua can be obtained. The image was taken on April 26, 2010. Note the Poa annua in the foreground that was untreated. Photo: Velocity

As any superintendent who has tried to renovate fairways can attest, killing the existing Poa annua with Roundup is easy, but keeping the seed bank from reinfesting the golf course is very difficult. In fact, without a viable herbicide program following seeding (see Branham and Sharp, 2011 for recommendations on Poa annua control in creeping bentgrass seedlings), many renovations end up with as much or more Poa annua than existed prior to the renovation program.

As an aside, soil fumigants are also effective, but the cost and environmental concerns when redoing fairways make fumigants a less attractive option. Remember too, that fumigants do not eliminate the Poa annua seed bank; they reduce the number of seeds significantly and tend to give a “Poa annua-free” window for germinating the new grasses. However, that window closes fairly quickly, and Poa annua begins competing with whatever species was planted.

I have one final point about Poa annua that is particularly challenging for any golf course that is considering a Poa annua control program. As mentioned above, the seed bank needs to be managed to achieve long-term control. That means the seed bank on the whole golf course—greens, tees, fairways, surrounds and roughs. Eliminating Poa annua on the putting green, a goal of many superintendents, will be more difficult if no effort is made to control Poa annua on the rest of the golf course. Poa annua seed will inevitably be deposited in the green by mower traffic, foot traffic, birds and more, requiring constant removal programs.

Also, since Poa annua is well adapted to shade conditions, removing Poa annua from shaded areas may result in reduced turf quality as less-adapted species struggle to grow. Before beginning a Poa annua control program, you must make the environment better suited to the species you want to manage. That means reducing shade, improving drainage and managing traffic—all factors that tend to favor Poa annua.

Control options

Golf turf managers have always had the option of controlling Poa annua from seed with a pre-emergence herbicide, but that strategy is ineffective without a means to control established Poa annua, such as a postemergence herbicide. In the past five to eight years, we’ve had several new products come to market that control Poa annua postemergence. Turf managers have been slow to adopt these herbicides because of the risks involved in trying to remove a grass that may constitute 10 percent to 50 percent of the turf present. There’s also the fact that these are all herbicides. That is, they kill plants. An inadequate margin of safety or unexpected environmental or chemical interactions can lead to unexpected turf injury, even with relatively safe products. Turfgrass professionals should never underestimate this.

With those warnings and caveats, I’ll update the status of new chemistries for Poa annua control in cool-season turfgrasses. Separate articles will focus on Poa annua control products for warm-season turfgrasses and cultural/mechanical techniques to help manage Poa annua.

Figure 3: A significant benefit of Velocity is its ability to suppress dollar spot. The area within the white plot marks received spring and early summer Velocity applications. The area outside did not receive fungicide and was riddled by dollar spot. Photo: Velocity

Prograss

The oldest of what I consider effective postemergence herbicides for Poa annua control is Prograss (ethofumesate). Prograss has been labeled for turf use since the late 1980s and can give good postemergence control of Poa annua in certain cool-season grasses. It is very safe on perennial ryegrass but only marginally safe on creeping bentgrass and Kentucky bluegrass. Prograss can provide effective control at most times of the growing season, but the best control is normally obtained with applications made four to six weeks before grass growth ceases for the winter. These applications don’t seem to kill the Poa annua immediately. Rather, the Poa annua is weakened and dies either over the winter or as grasses resume growth early the next spring. The problem is that these applications give wildly different results depending on factors we don’t understand. Literally, control can range from 0 to 100 percent and anywhere in-between. My own theory is that Prograss prevents Poa annua from reaching maximum winter hardiness, so depending on a number of factors—snow cover, winter temperatures, etc.—control is determined by the severity of winter stress. But again, this is just speculation.

As mentioned above, perennial ryegrass is extremely tolerant of Prograss, and Prograss is still widely used where perennial ryegrass is grown for golf course fairways. Prograss can be applied in the late season, but with perennial ryegrass, excellent Poa annua control can also be obtained within the growing season. Higher rates are required, but perennial ryegrass responds beautifully to Prograss applications. The turf becomes quite dense and dark green in color, similar to a PGR response.

Creeping bentgrass and Kentucky bluegrass are much less tolerant of Prograss, so lower rates are used when applying to these two species. Because of the lower rates, in-season applications are generally not effective with these two species and best results are obtained with September and October applications as described above.

Velocity

Velocity was registered for turf use in 2003. It was originally tested as a plant growth regulator, and Dr. Ron Calhoun, a Michigan State University turfgrass scientist at that time, spotted its herbicidal activity. However, because it is metabolized fairly rapidly by all turfgrass species, several sequential applications are required to get a high level of Poa annua control. While Velocity works, its adoption by golf turf managers has been relatively low. When used, it can control Poa annua rapidly, often leading to unhappy turf managers who may have underestimated the amount of Poa annua in their turf (or simply failed to appreciate what the turf would look like without any Poa annua).

Further, it is a growth regulator herbicide, so turf growth can slow significantly (this applies to creeping bentgrass as well), resulting in reduced quality turf, especially where traffic is significant. Secondly, there is typically some phytotoxicity associated with its use. This often is observed as a loss of green color of the turf. Under conditions of very high soil moisture or very cool temperatures the turf injury can be quite pronounced.

Finally, Kentucky bluegrass is generally injured by Velocity. From a practical standpoint, it is very difficult to apply Velocity uniformly to a putting green or fairway without getting some spray into the rough, which is usually Kentucky bluegrass.

Our own research has found that light (10 gm a.i./A or 2 oz. product/A), frequent applications give the best control. I normally recommend 2 oz. product/A applied twice per week (Monday and Thursday) for a total of six applications. This program typically controls >90 percent of the Poa annua on fairway height turf. However, this program is too aggressive if Poa annua populations are greater than 10 percent to 20 percent. When Poa annua populations are above this threshold, I recommend a different strategy that can lead to a gradual loss of Poa annua that does not result in voids or dead patches of Poa annua. The gradual control strategy calls for Velocity applications monthly during the warmer months of the growing season. Our best program would consist of monthly applications of Velocity at 2 oz. product/A from May through September. This approach injures Poa annua but does not directly kill it. Over time, Poa annua is outcompeted by less regulated creeping bentgrass. This program will not give complete control, but we typically see a reduction of 60 to 90 percent of the Poa annua. The value of this program is that turf injury is minimized and Poa annua reduction is gradual.

Figure 4: Prograss provides excellent control of Poa annua in perennial ryegrass. In the above photo, Prograss was applied 2-3 times in August and the photo was taken in early November. Note the dark green color from the Prograss-treated perennial ryegrass. Photo: Velocity

Xonerate

Xonerate (amicarbazone) is a new product from Arysta Life Science that was registered for turf use in 2012. Xonerate is a photosynthesis inhibitor that controls Poa annua postemergence in creeping bentgrass, Kentucky bluegrass and perennial ryegrass. Xonerate is very sensitive to high temperatures, and the label does not recommend applications to turf when temperatures are above 80 degrees F. Best results have been observed with spring applications when temperatures are cool. Fall applications, even when temperatures are cool, have been problematic.

The launch of Xonerate in spring 2012 gave mixed results. Injury to creeping bentgrass was observed at a number of locations, and creeping bentgrass varieties responded differently to Xonerate. Poa annua control was somewhat variable. Better results were observed in the Southeast, with more variable results in the Midwest and West. Additional research is under way to determine what factors control the activity of Xonerate.

PoaCure

There has been much buzz surrounding the evaluation of an experimental herbicide that is tentatively named PoaCure (methiozolin). I’m hesitant to spend too much space on an herbicide that is not yet labeled by the EPA. The literature is littered with examples of promising herbicides that never make it to market. What makes this product unique is its ability to slowly remove Poa annua from putting green turf. Most companies are afraid to label a product for use on greens because of concern over potential liability should any problems arise, while this product is being developed with greens as the intended target.

By controlling the number and rate of applications, a turf manager can control the rate at which Poa annua dies. Further, with this herbicide Poa annua doesn’t so much as die as slowly wither away, therefore allowing time for creeping bentgrass to cover any empty space. The result is a slow, almost imperceptible, transition to pure creeping bentgrass.

Results have been impressive to date, but the potential for creeping bentgrass injury under normal use conditions needs to be determined. The company is sponsoring an experimental-use permit with 166 golf courses around the United States that will run from 2014 to 2016. Expect EPA registration in late 2015 or early 2016.

Summary

While the number of herbicides available for Poa annua control has grown significantly, there still is a lot of Poa annua on golf courses. Herbicides like Xonerate and Prograss, when effective, result in a rapid kill off, often leaving the turf in poor condition with voids and thin turf. Products that can gradually remove Poa annua are obvious choices for golf courses that don’t wish to close for a renovation. Velocity used as a slow-killing growth regulator is the only current choice that gives a gradual rate of control. Should PoaCure reach the market, it too offers gradual control and good turf safety.

Golf turf managers should consider that a major part of the battle against Poa annua is cultural. Keeping a dense, healthy turf is the best defense against Poa annua invasion. Ball marks, divots, surface disruption from aerification, and voids in general, give Poa annua a foothold. From there it’s all downhill for such an invasive, competitive species.

Bruce Branham, Ph.D., is a professor of turfgrass science at the University of Illinois and can be reached at bbranham@illinois.edu.

References

Branham, B. E., and W. Sharp. 2011. Annual bluegrass control in seedling creeping bentgrass with bispyribac-sodium. Online. Applied Turfgrass Science doi:10.1094/ATS-2011-1103-01-RS.

Calhoun, R. N. 2010. Growing Degree Days as a Method to Characterize Germination, Flower Pattern, and Chemical Flower Suppression of a Mature Annual Bluegrass [Poa annua var reptans {Hauskins} Timm] Fairway in Michigan. Ph.D. Diss., Michigan State Univ., East Lansing, MI.