Unnatural factors that could lead to tree troubles on the golf course

Unfortunately, trees and shrubs on the golf course can’t take care of themselves. Like the turf on the tees, greens and fairways, there are all sorts of abiotic maladies caused by nonliving factors that can influence their demise.

Regardless of the specific cause, the keys to success are the same. A step-by-step approach, beginning with an accurate diagnosis, should guide the process from start to finish.

Along the way, honing in on the most effective treatment options and an honest assessment of the tree’s value to the course will result in retaining an ornamental as an asset rather than an eyesore or a liability.

An accurate diagnosis

At the outset, it’s helpful to think of the diagnosis process as an all-things-considered, eyes-wide-open endeavor.

Jumping to conclusions with preconceived notions usually leads to an inaccurate diagnosis. Another initial consideration is to define “malady” or “disease.” While there are many, perhaps the best one, in this case, is any factor that limits a plant from reaching its full potential.

This definition is truly in line with the open eyes and all-things approach. Overall, the best path is to start with general influences and gradually begin narrowing the scope and number of possible factors.

Considering various problems in three categories of causes is helpful in terms of finding the actual limiting factor … general influences, species-specific ailments and a set of responsible agents, both biotic (insects, mites, fungi and bacteria) and abiotic.

Generally speaking

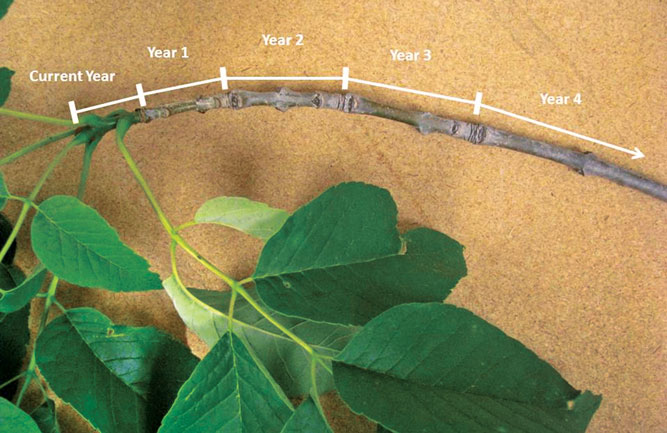

One symptom of soil compaction is a slowdown in growth over the years. (Photo: John Fech)

Many influences affect a wide variety of — if not all — trees. They include site-related conditions, the forces of Mother Nature and the negative impacts of ill-advised maintenance activity.

Gathering relevant historical information about the location on the course, both in recent times and over the past 5-7 years (utility line trenching, soil moved over roots, cold winters, hot summers, irrigation system breakdowns) is also useful.

Some typical examples include:

-

Temperature extremes can cause significant damage to trees and shrubs. (Photo: Lori Stepanek)

Soil Compaction. Compressed soil particles leave less room for oxygen and water to flow between them and be available for future root growth. Construction equipment is the most common cause of compaction. Chronic mower and foot traffic can also lead to long-term injury. The classic symptoms of compaction are stunted stems, usually seen in shortened internodes over time. Prevention is paramount through the redirection of traffic, extensive mulching and fencing during construction activity.

-

Unfortunately, herbicides that target turf weeds can also damage trees. (Photo: Neil Formak)

Slope. Slope has the effect of preventing the infiltration of water into the root system of woody plants. A double influence occurs when the soil root zone has been compacted previously, facilitating the movement of the water downslope. Superintendents should check soil moisture content with a simple screwdriver test to determine if they need to make any adjustments.

-

Low-pH soils often tie up essential elements that some trees require to photosynthesize. (Photo: John Fech)

Basal trunk damage a.k.a. mower blight. String trimmer and mower injury to tree trunks are quite problematic, as this area of the tree is at a critical location for water and nutrient movement from the roots, up the trunk and into the crown. It can occur slowly with small taps and slices or with a single major force. Contrary to popular belief, both are equally injurious. Prevention is the key; placing wood chips, bark chunks or pine needles over the roots around the base of the tree (but not on the trunk) goes a long way.

-

The forces of Mother Nature such as hail damage are typical of a general abiotic malady. (Photo: John Fech)

Planting Errors. Correcting an improperly planted tree later in life is impossible. Common errors include planting a tree too deep, digging a smaller-than-needed sized hole and mixing sand, compost or topsoil with the native soil that is backfilled over the roots. Prevent these problems by placing the first lateral root of the root mass at or slightly above the final grade, and digging a planting hole three times the width and no deeper than the root mass.

- Herbicide Injury. Wind speed and proximity to the canopy are the biggest factors in herbicide injury to trees. Roots can take up certain active ingredients, such as dicamba, causing damage. Reversal of herbicide injury is usually not possible, so prevention is paramount. Good prevention methods include spraying only when wind speeds are less than 5-to-8 mph, using large droplets and low-pressure equipment and directing the formulation only on the target weeds through spot treating instead of the tree.

- Temperature Extremes. When trees experience wide variations in temperature, the leaves, needles, roots and stems dry out. The spring, when a tree forms new shoots, mid-to-late summer, when roots can desiccate, and the middle/end of winter when drying winds blow over leaves are the most critical times for injury. In summer, this injury usually appears as marginal leaf/needle browning. In winter, lifeless, brown tissue is common. Keeping soil moisture in the moist range is a good preventative step, but that only goes so far, as damage is inevitable in some years.

Wide, not deep, planting holes lead to the development of strong lateral roots. (Photo: John Fech)

To get specific

The diagnosis of problems in woody plants is a two-step process — first, identify the plant, then the malady.

In addition to the general influences, certain abiotic factors tend to be associated with specific plants or groups. Also, consider causes that the tree/shrub species are known to contract, for example:

Wide, not deep, planting holes lead to the development of strong lateral roots. (Photo: John Fech)

Sunscald

Young and thin-barked trees such as birch, maple, aspen, crabapple and honey locust are historically associated with sunscald, which occurs mainly in winter when the sun warms and softens the bark. This happens on the south and west sides during the daytime and is followed by freezing temperatures at night. Splitting, cracking and exposure of the thin water/nutrient movement cambium layer to the elements results. Superintendents can prevent sunscald by installing light-colored PVC collars on the lower trunk in late winter and removing them in early spring.

Failure to spread roots out in the planting hole leads to the development of stem girdling roots. (Photo: John Fech)

Chlorosis

When planted in high pH soils, chlorosis often develops in trees that prefer low pH, including sweetgum, river birch, pin oak and silver maple. This condition is a general term that describes the symptoms of the inability to transform nutrients from the soil into adequate carbohydrates and sugars necessary for growth. In high-pH soils, some needed elements such as iron, manganese and magnesium are tied up, making them unavailable for root uptake. Again, prevention is the best control method, avoiding planting trees with a historical issue with chlorosis. Treatments can be implemented, but in most cases are short-term fixes and should be used only for high-value trees.

String trimmers and mowers can cause varying degrees of injury. (Photo: John Fech)

Trees that don’t tolerate wet soils, such as trees near greens that are frequently and thoroughly watered, are often damaged by a lack of oxygen in the root zone, created by the replacement of air with water. Proactive species selection at planting time is the best approach for this malady. Certain species, such as red maple, river birch, cottonwood, honey locust, dawn redwood, London planetree, swamp white oak and bald cypress are well adapted to wet soils. Intolerant species include hickory, dogwood, sassafras, red oak, bur oak, linden, black walnut, beech and buckeye.

Sunscald destroys the all-important conductive vessels of a tree. Photo: John Fech)

Desiccation

Desiccation in winter of the leaves of plants such as hollies, arborvitae, yews and boxwood can cause major injury. Once damaged, these plants often do not recover. Anti-desiccant sprays have been used in the past, however, recent research by Washington State University has cast doubt on their effectiveness and documented a reduction in photosynthetic activity because of their use. Pruning and removing damaged stems as well as avoiding planting these species in windswept areas is the best solution.

Closing arguments

Comparing the appearance of these influences with biotic agents brings clarity to the diagnosis. For example, when diagnosing damage to spruce, photos in university references of known insect or fungal problems such as spruce spider mites or cytospora canker usually look different from abiotic issues.

Another aspect of the comparing technique is to consider that the symptoms of biotic agents usually are spotty or random in trees and shrubs, whereas abiotic influences are frequently found on one side of a plant or the entire plant.

Approximately 70-to-80 percent of the time, several abiotic factors or a combination of abiotic and biotic factors are causing the symptoms. Rarely is only one influence responsible for tree decline. As outlined above, taking steps to decrease abiotic stresses will allow plants to be more resilient towards biotic stresses. In most cases, well-chosen preventative steps are the key to success, rather than relying on curative treatments.