Treatment of iron deficiency and chlorosis

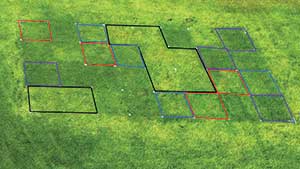

Turf response to foliar iron fertilizer applications. Plots outlined in black received zero iron fertilizer. Red plots and purple plots received 0.4 and 1.6 oz. iron per 1,000 sq. ft., respectively, from iron sulfate (Extreme Green 20, 20 percent iron by weight). The blue boxes were treated with 0.4 oz. of iron per 1,000 sq. ft. plus citrate and EDTA chelates at 2 oz. per 1,000 sq. ft. product from Iron Chelate 20. (Photo: Bill Kreuser)

Iron (Fe) chlorosis of Kentucky bluegrass and creeping bentgrass can be a perennial summer problem. Symptoms usually include light yellow or lime-green leaves in July and August. Scientists believe that iron chlorosis is a root dysfunction that occurs when soils are hot and/or wet. Grasses make natural chelating molecules, phytosiderophores, which help extract micronutrients like iron and zinc from high pH soils. It’s likely that this nutrient mining system slows or stops when the soils are hot and wet.

Iron chelates were tested on a Kentucky bluegrass stand at Heritage Hills Golf Course in McCook, Neb. We applied iron fertilizer as iron sulfate or with common chelates like EDTA, DTPA, citric acid and a less common turf chelate, EDDHA. Treatments were watered in after the first application to limit foliar uptake.

After several weeks, there was no improvement with all the tested iron treatments. One month after the first treatments, we reapplied iron treatments but did not water them in. The differences were remarkable. We concluded:

1) Only foliar iron fertilizer applications reduced deficiency symptoms. Don’t water in Fe.

2) Deficiency symptoms improved with increased iron fertilizer rate (1.6 oz. Fe/1,000 sq. ft. maximum application rate tested).

3) The chelated products did not outperform the cheaper iron sulfate (aka ferrous sulfate).

If iron deficiency is a perennial problem for Kentucky bluegrass, avoid excessive irrigation, make foliar applications of iron fertilizer and don’t water it in.