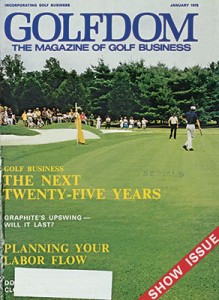

The Golfdom Files Extended: The next 25 years

For the January 2015 Golfdom Files, we took a step into the time machine and brought out an article that ran exactly 40 years prior, from the January 1975 Golfdom.

The Next 25 Years

The Next 25 Years

By Jerry Claussen, National Golf Foundation Consultant, Rocky Mountain Region

Whatever happened to colored sand in bunkers, synthetic grass for greens and lighting of full-length courses?

These were ideas in past years presented by persons in the golf industry that did not, for one reason or another, get far. But there are plenty of new trends and ideas that are changing the business of golf every day.

We see signs everywhere. The PGA Tour competes with tennis for TV time. The price of fertilizer and chemicals has doubled this year. Russia will soon have its first golf course.

There are only a few clues to what is happening. Here are some of the major trends in golf course development and operation that are significant.

Fighting slow play. A strong movement is spreading to find a remedy for slow play that has been choking our busiest courses for years.

The National Golf Foundation made slow play a high priority about six years ago with a humorous promotion campaign using “Speedy” and “Mrs. Speedy,” depicted by rabbits.

A starting time system to utilize all of the course for more hours, with maximum time for playing each nine, was sent to every course. The attempt was commendable, but the results not very noticeable. Then, one by one, golf industry leaders started trumpeting the need for speedier play. Finally, the idea is catching on. Even PGA officials have been tough as they threaten and occasionally levy penalties on slow players.

Many public course operators have picked up ideas for faster play. Most now have 150-yard markers for faster club selection, start nine-hole players from the 10th tee when it is open, use rangers and teach rules and etiquette to beginning classes.

More are using realistic spacing of starting times to avoid jam-ups, reminder signs in the pro shop, on the course, and even on the scorecards suggesting how much it should take to play each hole, nine and 18.

An example of a sign is on the seventh tee of Brookhaven Country Club, a 54-hole club near Dallas: “Par for playing time to this tee should be one hour and 33 minutes. How is your score today? Everyone enjoys the game more when play moves on time. We appreciate your help. Thanks… Your Board of

Directors.”

A more expensive game. Golf has been called the “game of a lifetime.” It may be open to almost anyone of any age, but at what price? Inflation is hurting the business.

Private membership clubs have been trying desperately to keep ahead of cost increases. Many are raising dues, imposing house minimum charges, assessing members for losses, raising prices for food, beverage and other services, and/or seeking more outside party business. Increases in the minimum wage, higher costs for food and other services, plus rising taxes, have forced these increases. We have seen monthly dues go from $70 to $90 at one club, $38.50 to $45 at another, and the imposition of a $20 per month house minimum charge at another in the Denver area.

Middle-income families who have access to less expensive tennis and swim clubs are no longer lining up to join some suburban country clubs. The so-called “status” means much less to our mixed, mobile, more open society than in previous times.

Even the cost of playing golf is soaring. Municipal courses that once charged $2 to $3 for 18 holes all day, now charge $4 to $5. Season tickets at the courses are up to $125, $150 or more. Privately owned daily fee courses report green fees up to $7 or $8 for eighteen holes on the weekends.

And if the typical club member pays dues of $876, $73 a month, at the latest Harris-Kerr-Forster survey tells us, and plays even 30 rounds of a golf season, that is almost $30 a round, not counting the cost of golf car or caddie, lunch, bets and a couple of golf balls dunked in the lake.

More municipal courses. Municipal golf for too long has been the poor cousin of the golf business, expect in how many people it served. But no longer.

A combination of factors — urban population pressures, public interest in open space and ecology, increasing development costs, Federal support through the BOR grant program, lots of national publicity about the need for public courses and how they can be built — contributed to this trend.

The results are encouraging. In 1973, 38 new regulation municipal courses and 58 municipal projects in all opened for play Both the 38 new courses, and the ratio of 21 percent to all new regulation courses, were new records. Another 45 municipal projects, or more than 15 percent of the 290 reported, started construction, and 31 of these opened in 1974 through Labor Day.

Local government can and does use many methods to create public golf facilities. Johnson County, Kan., purchased a former private club last year. The city of Plano, Tex., leased lean to a partnership of former PGA tour players to build and operate a public course subject to city regulations. The city of Arvada, Colo., purchased a bankrupt daily fee course on leased land, will also buy the land, and lease the business to private operator for 25 years.

Executive course concept spreads. The name executive course no longer fits the category because the short, intermediate course has caught on among all types of golfers. Not boring like most par-three courses, the executive is also not long, difficult and time-consuming like many regulation-size layouts. Families, women, seniors, and even rushed executives are finding new, well-designed intermediate course a happy golf experience.

At the end of the 1973 NGF counted 552 of these courses in the United States, including 328 clubs having only an executive course. More than 60 percent were nine holes, many of these additions to regulation golf courses. About 70 percent were daily fee, indicating how popular they are with the public and profitable to their owners. The resort-retirement areas of California and Florida led in numbers Forty-one states reported at least one.

The trend is continuing. Thirty of the intermediates opened in 1973, and 27 in 1974, compared with 18 in 1972. Another 28 were reported under construction in 1973, almost double the 17 of 1972, and 24 more to September 1974.

The golfers not only like them, so do developers, whether a private club, real estate combine, or a municipality. The short courses use less land, are usually less expensive to build and maintain, faster to play, and can produce more revenue.

Golf attracts big corporations. It has seldom been a cheap venture to enter the golf business. Now land costs near population center have soared to $5,000, $8,000 and more an acre. Design and construction standards are higher than ever. Construction and material costs are escalating fast. Big capital is needed to buy land, build course and clubhouse, equip and hold on for two, three or more seasons of operating at a loss until the business gets established.

Not that golf business is not profitable in the long run. In recent surveys it has been shown that in most years up to 50 percent of private clubs run in the red. But other surveys consistently reported that 90 percent and more of daily fee and municipal courses make money.

With costs rising, and potential for a good profit in operation and appreciation — enter the large corporation.

Nearly half of all courses opened in 1973 and now under construction are part of large real estate developments. Nearly 500 projects have opened in the past four years, 142 in 1973 alone. Some of these are part of conglomerate chains — Diamondhead Corp., McCulloch Oil, Great Western Cities, and Rockresorts, Inc.

Most of these groups had little or no previous golf course development or management experience. They simply hired knowledge. Their primary goal in almost every case is to sell real estate. In some cases, however, even despite lavish advertising and promotion campaigns the courses have often been sterile, the service impersonal and the cost astronomical.

Also among the new corporate ownerships are the Japanese, who have purchased or are developing several clubs in Hawaii and California as investments and homes-away-from-home for traveling businessmen. Japanese interests own at least 10 courses on American soil, including Mesa Verde Country Club, Costa Mesa, Calif., Canyon Hotel and Country Club, Palm Springs, Calif.; and Incline Village Golf Club and Ski Resort, Lake Tahoe, Nev.

Course Design. There are more first-class, well-designed, well-maintained golf courses in play today than ever before. Probably 75 active individuals offer good credentials as golf course architects. The American Society of Golf Course Architects, the elite of the profession, has more than 60 members.

So why are we still seeing so many bland, dull courses with a mass-produced look? Why so many small tees, bad drainage, inadequate pumping system?

For one thing, only about one-third of the 300-plus facilities opening each year are designed by professional golf architects. The rest are products of well-meaning private owners, local golf pros, citizen committees and other pretenders. The result in most cases is disasters for golfers and superintendents who must maintain them later.

Pros are more professional. For years the PGA has been claiming that club professionals and their bright young bright young assistants are trained as businessmen to offer golfers the best service. For awhile it was more wishful thinking than fact, but now the dream is coming true.

Requirements that new apprentice pros must attend a series of business schools, and old pros are supposed to keep up new techniques, have done much to upgrade the golf shop business. Just this past spring, the PGA sponsored eight national business schools. A staggering 375 professionals attended the Metropolitan PGA Section’s annual education forum on April 8.

When a new course opens, the ownership frequently has a choice of a half-dozen or more qualified golf professionals who are trained in running a shop, hiring assistants, buying and selling merchandise, teaching, and know public relations and promotion.

We seldom visit an urban club pro shop anymore that does not look well-stocked, neat and clean, with staff and service to match. Most of today’s club professionals are, act and talk like gentlemen, businessmen and true pros.

Women share the chores. Slowly but surely the equality of women has affected the golf business. Maybe most golfers would to like to restrict them to Ladies Day one morning a week, but they keep the clubhouse busy, do a good share of buying in the pro shops, and now are sharing in operations too.

Women club members are no longer unique, and there are perhaps 200 or so women teaching professionals at larger clubs and resorts. And a few are running the whole golf shop business.

A big breakthrough in women’s employment has been in course maintenance. After a few superintendents let down the sex barrier, others have tried it and liked it.

Every superintendent with female crew members reports the same good results — they are hard workers, reliable, neat and dedicated. Women can do almost any job from mowing fairways and greens to raking traps and doing clubhouse landscaping.

Girl caddies are part of the trend too. The golfers accept them, and the trend too. They have a future too, because the Western Golf Association reports that seven girls have already won Evans caddie college scholarships.

Higher maintenance cost. Like most things, the cost of maintaining our golf courses keeps going up. That should not surprise anyone in the business, but club members and golfers paying the bill have to be educated.

The annual Harris-Kerr-Foster survey of 100 of the most elite private clubs in 1972 reported an average maintenance bill of $6,554 per hole, or nearly $118,000 for an 18-hole course. That was up five percent over the previous year. After that came the 1973 energy crisis, and rising costs for fuel, pipe, seed, plastic materials, fertilizers and chemicals.

Superintendents at most courses were smart and stockpiled fertilizers before the price boost in 1974. But the crunch is coming for the 1975 season. Budgets will increase 10-20 percent this season over last. Superintendents and their bosses always want to improve the course, not let it backslide. One prestigious western private course was maintained for $96,000 on 1973, but is working on a budget of $120,000 this season.

Sewage effluent for irrigation. The fuel crisis emphasized that prosperity and growth are not forever, but rather are limited by natural resources. So it is with water.

Where supplies are short, politicians and the public frown on golf courses using clean, potable water that might otherwise go for drinking, moving industry and watering lawns. If a course does not already have its own exclusive, reliable source of water, such as a lake, river or wells, it may be in trouble sooner or later.

We are short of water in this country now, especially in the Northeast and West. Many new courses built in recent years in the West have turned to treated sewage effluent for irrigation. In most cases there have been no damaging effects to either fine turf or humans. In many areas, courses have become an ideal outlet for using millions of gallons of treated effluent not useful elsewhere.

Automation and mechanization. Machines have become important in golf operations.

In large private clubs, membership accounts and billings are frequently handled by a computer program. In the kitchen, pre-packaged foods and big freezers and microwave ovens have replaced the fry grill. More and more courses are irrigating with automatic time clocks.

New machines have made quite an impact on golf course maintenance. Equipment manufacturers have been diligent in visiting courses and turf conferences, listening to superintendents on what they need, and then producing machines in answer.

The riding triplex greens mower has been in use for five years. Perhaps 80-90 percent of all the 18-hole courses, and many with nine holes, have switched from walking to riding. Very few machines have been turned back or traded in, distributors report. Some superintendents have converted their first riding mower to a tee mower, then bought a newer model for greens.

Such a machine now costs about $3,500, and it should have a life of five to 10 years. Properly trained, anyone can cut greens and do a smooth job. Predictions that greens would be compacted and grainier have been mostly false alarms. The riding mower can cut 18 greens in three to four hours using walking mowers.

One distributor reported he had received 26 riding mowers for this season, and sold out before the season started. “Because of labor saving, none but the richest clubs can afford not to have one,” he said. Because of materials and parts shortages, however, orders are backlogged about six months.

Another great innovation is the riding trap rake. Available just the last two years, the concept successfully fits the trend to save time. Perhaps 50 percent of courses with any great number of traps now keep them in shape with tractor-pulled rakes.

Large tree spades, usually rented from landscaping firms, have been a godsend for old courses replacing dead or damaged trees, and to new courses on open land. Such machines make moving 20-foot pine a routine task.

It hardly seems that automatic irrigation could get more sophisticated, but new types of heads and controllers appear on the market each season. In machinery, better ideas are on the way, such as a combined vacuum and finger-raking machine. How about a golf car riding on an air cushion?

Where are the new trends taking us? How big will golf be by 1980 and 1990? Predicting the future is always risky, and it seems we always under-guess. Golf is now a world-wide game, but still far short of its potential popularity and market. For the final quarter of this century, growth should only be limited by providing enough places to play at acceptable cost.

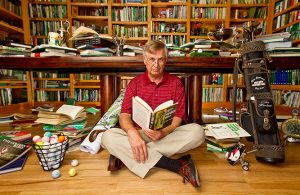

Photos: Golfdom Staff