The Golfdom Files Extended: How to get the most out of fertilizer

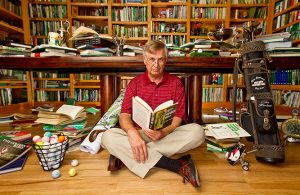

Believe it or not Editor-in-Chief Seth Jones is not the most famous person to have ever written for Golfdom. Of course our founder was Herb Graffis and the pages of Golfdom have seen high-profile members of the industry contribute stories, like this article from our March 1955 magazine.

Believe it or not Editor-in-Chief Seth Jones is not the most famous person to have ever written for Golfdom. Of course our founder was Herb Graffis and the pages of Golfdom have seen high-profile members of the industry contribute stories, like this article from our March 1955 magazine.

H. Burton Musser led the turfgrass management research and teaching for three decades at Penn State University. For all of the non-Nittany Lions out there you may know his name from the Musser International Turfgrass Foundation and its Award of Excellence given annually to Ph.D. students since 1989.

In this edition of the The Golfdom Files Extended we present Musser’s full article on how superintendents could get the most out of their fertilizer in 1973 after.

Since 1948, when publication of turfgrass conference proceedings first became general, there have been 33 major talks on fertilization problems at 12 state and national conferences. During this same period more than 25 articles on the same subject have been published in popular magazines such as the Golf Course Reporter, Golfdom and the U.S. Golf Association Journal. In addition, better than 50 papers dealing with some phase of fertility that has a direct bearing on turf, have appeared in the Agronomy Journal, Soil Science, and other technical publications.

A review of this rather impressive mass of published material shows several very interesting things. In the first place, it gives us a quite complete cross section of modern thinking in this country with respect to the use of fertilizers on turf. Secondly, it shows a surprisingly high degree of agreement, not only on basic technological principles, but also on the way in which these principles should be applied. It is the latter consideration, that is, the application of basic principles to practical fertilizer practices, with which we are primarily concerned, in attempting to determine how to get the most out of fertilizers.

Controlling Factors

An analysis from this standpoint of what has been said and written shows that our knowledge of the subject can be classified into five main concepts, or groups of facts and procedures. These are the controlling factors in successful fertilizer use. They include:

1. The tremendous influence of the soil on the kind, quality, and effectiveness of the fertilizers we apply.

2. The specific differences in the fertilizers themselves.

3. The way in which grass uses nutrient materials.

4. The procedures and practices best adapted to conform with and take advantage of the above technological facts. And, finally

5. The economic considerations involved. Cost always is a factor in any fertilizer program.

Let’s examine each of these categories. The task is relatively easy with respect to the first 3. These are all technical relationships to practical fertilizer use and there should be no necessity, therefore, for further elaborating the importance of the relationship between these basic principles and actual practice. We have the basic facts. Our chief concern is — do we use them? Do we apply what we know? For example — it is well recognized and generally understood that phosphorus is held strongly in the soil and that losses of this element are negligible. In spite of our knowledge of this fact the evidence indicates that all too frequently there is a tendency to continue liberal applications of high phosphate fertilizers when there is no longer a need for so much. Soil test records are available for 198 greens in Pennsylvania golf courses in 1953. Over 60% of these showed a high to very high available phosphorus content and over 43% were very high. In some cases the soluble salt content of greens was approaching dangerous levels. In spite of this there had been no change in the fertilizer program responsible for the condition and in certain instances none was made even after the records were in. Obviously, this is not making the best use of fertilizers.

Nitrogen is another example. We have the information on how plants use it, what happens to it in the soil and in what form we can get it (what’s in the bag). Are we using this information in such a way that we can expect to get the most out of the fertilizers we apply? This is of even more vital concern, now that liquid and high analysis completely soluble fertilizers are becoming available. It will take all our knowledge and considerable good judgment to handle these materials without achieving a really magnificent amount of waste and perhaps running into serious trouble, to boot. Since nitrogen is the key growth element and is exhausted much more rapidly than the phosphorus and potash in these materials our program of use must be based primarily on nitrogen needs. Quantities, and frequency of applications must be adjusted to provide a constant and continuous supply of this nutrient. Unless we watch the proportions of the various nutrients in the materials we use it is quite conceivable that in getting on a sufficient amount of nitrogen we will squander phosphorus and potash.

Relationship to Soil Condition

To further emphasize this dependence of maximum fertilizer utilization on basic principles let’s look at its relationship to soil physical condition. When fertilizer is applied to established turf the only way in which it can get into the soil is to be dissolved in water and carried down. This is true whether it is applied in dry form or as a liquid in which it is in solution. If water does not penetrate because of heavy thatch or surface compaction, the fertilizer cannot do so. Unless it gets into the soil where roots can absorb it, it is of little value. Under such conditions the best correction is opening channels for its penetration by mechanical methods. Critical studies at the Pennsylvania Agricultural Experiment Station have shown over 50% more phosphorus in soil at a 2-6 in. depth 6 weeks after a single mechanical aerification than on the same unaerated soil. Certainly this would seem to be one way of getting the most out of fertilizers.

There are many other things that have a bearing on the return we get from the fertilizer we use. Are applications adjusted to the kind of grass we are fertilizing? Fescues and bluegrass make their best growth in the cooler parts of the growing season. They need their greatest supply of nutrients, particularly nitrogen, at these times. Actually, they may be seriously injured by attempts to force them into rapid growth during the heat of mid-summer. Bents are not so much affected. They can and do utilize larger quantities of nitrogen throughout the growing season. This is why so many superintendents have been using slowly available forms of nitrogen in their fertilizer programs. As turf goes into the hot weather the nitrogen supply is gradually reduced. The grass adjusts growth rate to the lower supply and becomes tougher and less susceptible to injury. The same effect may be achieved with frequent applications of small quantities of soluble forms of nitrogen. The trick is to know what quantity to use and how often to put it on. In contrast with cool season grasses Bermuda and the other warm season grasses make most of their growth during the summer. If we are to get maximum effects they must be fertilized when their needs are greatest. In the spring, to give them a start, then followed by supplemental applications whenever deficiencies begin to show. Certainly liberal applications toward the end of the growing season will keep them growing and hold color longer into the fall. Water has a direct and major effect on efficient fertilizer use. This is especially true on the lighter types of soils. Sands and sandy loams do not have the same ability to hold nutrient materials, nitrogen particularly and potash to a somewhat less extent, as do heavier soils. In periods of heavy rainfall or when watering is not carefully adjusted to the moisture absorptive capacity of the soils removal of nutrients in the drainage water becomes an important factor. In addition, grasses grow faster when water supplies are adequate and so use more fertilizer. If we are to get the most out of fertilizers quantities and frequency of application must be adjusted to water situation.

Complications of Weed Problem

Weeds are another important consideration. Heavy infestations of Poa annua or crabgrass on greens and fairways tremendously complicate the fertilizer picture. Obviously, it is not good technique to apply fertilizer at times when the weeds are growing best and will make more effective use of the fertilizer than the grass. There is no question but that there have been instances when the weed problem was intensified in this way. The solution, however, is not simple. There are many times when fertilizers must be used to keep the grass in condition so that it will be better able to combat weed invasion, even though there is danger of weed stimulation. Where this is a serious problem, often, we get the most out of fertilizers only when they are used in connection with herbicidal treatments which will eliminate the weeds or set them back to such an extent that they cannot seriously compete.

Much has been said and written about rates of fertilizer application. Certainly it is an item of first importance in considering the economics of fertilizer use. Too little is just about as uneconomic as too much. There is not enough to produce the results we expect and must have. We have invested money without an adequate return. So, how much is enough to do the job? This is one of the most difficult problems which a superintendent has to meet, and, unfortunately, there is no simple, blanket formula that can be applied. Are clippings removed or allowed to remain? What is the soil reaction and physical condition? What do soil tests show with respect to phosphate and potash levels? Do growth rate or tissue tests of the grass indicate that nitrogen is getting low? What is the watering program? What are the characteristics of the fertilizer itself? Is the nitrogen in slowly available form or is it completely soluble? What kind of grass is to be fertilized and how is it managed? And finally, what is the weather? These are some of the important things that must be recognized and correlated when we attempt to arrive at optimum rates of application. An understanding of them and ability to apply that knowledge is a part of what gives the position of Golf Course Superintendent a professional rating. The results of experiments and technological studies of the various relationships can give him the background information that will help to form sound judgments, but maximum results will be achieved only as they are interpreted in terms of the conditions and needs on the individual courses. (Incidentally, that applies not only to fertilizer programs, it applies to every management practice connected with golf course maintenance.)

Cost Factors

Finally, any discussion of getting the most out of fertilizers cannot ignore the cost factor. The actual dollars and cents value of “what is in the bag or bottle.” Certainly, the actual cost per unit of plant nutrient materials plus differences in time and labor of applications must be considered. If a unit of nitrogen in one fertilizer costs twice as much as in another this must be taken into account. But, is first cost the only thing, or, always, even the most important thing? Undoubtedly, it would be, if all nitrogen was in the same form and could be handled in the same way. Unfortunately, this is not the case. There are material differences in rate of availability, safety and ease of application, frequency of application, stimulation of growth, and rate of loss.

The ultimate aim on the golf course is to produce a good playing turf of uniform quality throughout the entire season. We abhor peaks of rapid growth and succulence, and valleys of starvation. Both experience and experiment have shown us that these are the things which cause trouble. Because so many things beyond our control contribute to the rate at which immediately available forms of nitrogen are consumed or lost, it becomes extremely difficult to determine just when, how often, and at what rate such materials should be applied. The popularity and wide spread use of the more slowly available natural organics is excellent evidence that this is recognized and that other considerations beyond first cost are involved, in fertilizer use. This should not be construed as an argument for or against any particular form of fertilizer. It is simply an attempt to marshall the facts that must be considered in trying to get the most out of what we use. There are times when we need quick action. There are others when we do not want it. An ability to recognize what we need and when we need it and a knowledge of what formula, or material will best meet the situation, these are the secrets of getting the most out of fertilizers.

Photo: Golfdom