The Golfdom Files Extended: Confessions of a club pro

In December 2014 issue we published an article from the May 1967 issue of Golfdom written by an anonymous club professional. The pro goes into detail about his day-to-day relationships with the club administration and membership.

Despite all of the challenging relationships he wrote about in the 4-page story, he still loves the job. Take a peak into the mind of this professional in a world well before the mechanized and automated place we live today.

Despite having every member — and his wife — as his boss, the life of this professional is not without its compensations.

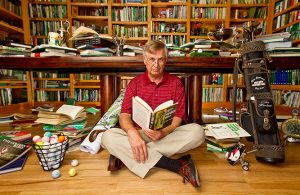

A professional at a private golf club has the toughest of all the sports jobs. I ought to know — I’m one and I love it.

The number of bosses a pro has is only limited by the membership, for his boss is every member — and his wife. He has to make a year-round living for his family in an active season that’s only five to seven months long at clubs in the Central and Northern states.

He and his family have to live on a scale that will be a credit to the “class” of his members and their club. But if he, his wife or children, happen to have something better than an envious member, better look out! Club officials change often, and the pro can become the victim of club politics.

Frankly, professionals haven’t always been intelligent in dealing with the risk. They’re inclined, for example, to pretend they’re making more money than they actually are. Officials of their clubs see the total of charge tickets for pro-shop merchandise and lessons in club books, and may assume that the pro is making a big income for six months’ work. But I’ve never met a club official who came within 20% of guessing a professional golfer’s expenses of doing business.

Why, my laundry and dry cleaning bill alone during summer usually represents the gross profit on the sale of at least ten sets of clubs. Many a summer day I’ve had to change clothes three times. The members expect me to be immaculately groomed. That costs money — as my wife well knows when she tartly compares the extent of her wardrobe with mine.

How easy are the hours of the professionals at his club? He’s on the lesson tee by 9 a.m., after having checked over operations in his shop and briefed his staff on the day’s work. He takes an hour off for lunch and eats his dinner at the club so he can be around for teaching tired businessmen. It’s a rare day that the pro gets home before dark.

On Mondays, his so-called off day, he must make the rounds of display rooms and buy merchandise for his shop. On other days he must somehow find time to talk to salesmen, because the pro shop must be kept properly stocked.

The tournament professional can take his prize money with a fast “thank you” and be on his way. The home-club pro, however, is expected by some of his members to bow in worshipful appreciation whenever they buy tees.

Everybody who belongs to a club is equally important to the pro. The professional’s only smart and safe policy is to play no favorites even though — simply because of personality and shop and lesson patronage — he would be normally inclined to favor those who are most considerate of him.

Think of what happens when he stars the day by giving an hour’s lesson to a woman of nervous and ambitious temperament who has been condemned by nature to play in a high score. The professional feels that he’s really achieved something if he can just get her to shoot consistently. The lesson is always more of a strain on him than her.

Then, when some other woman who has a knack for golf takes a few lessons and shows results, the one to whom the pro has devoted the most nervous and physical energy is sure to think he has given the talented woman more of his attention.

Many a pro has lost his job because of his lack of finesse or discretion in his treatment of women members. A young, good-looking fellow on the lesson tee has to be strictly professional in his attitude toward women.

During the course of a long summer’s day, a pro may give as many as nine or ten lessons, and at the end of the day he is a weak and weary man. When he darts into the clubhouse between lessons to get a glass of milk for his ulcers or change his shirt, some member is sure to hail him in the men’s locker room to “visit.” The pro stays a few moments, then apologizes because someone is waiting for a lesson.

If the pro does not sit down for a clubby chat with the member, he may spread around that the pro is so hungry for a dime that he won’t stop to say a few kind words. On the other hand, the member who has had a five-minute wait on the tee may accuse the pro of being more interested in talking than in giving lessons.

A pro must please 350 bosses and their wives or have club politics catch up with him. New administrators at clubs often don’t come into office until early spring. Then it’s too late for the pro — who is dropped without warning — to find another job. The professional, who is supposed to be responsible primarily to the chairman of the committee that hired him, is in reality held personally accountable by every member of the club.

Pros can make mistakes, of course. I’ve made plenty of them — some of thoughtlessness and some of sheer ignorance. In honest reflection, however, I am sure that I’ve made fewer mistakes in my relations with members than they have made in their relations with me.

So many members simply don’t realize what the conditions are. When they see me playing golf — which isn’t very often — they think I have an easy job and am out on the course entirely to enjoy the company of some other favored member. Usually I am giving a playing lesson. Only on Monday afternoons, when I rush from my shopping to the first tee of any tournament our professional association may be having, do I get a chance to play for the fun of it.

I like to play with as many club members as I can. (Not for bets, though. The pro who gambles heavily with any of his members is not handling his job properly.) However, strangely enough, it isn’t always easy to get good game with members; some of them are embarrassed when I’m along, due to their high scores.

If they only knew it, they teach me how to enjoy golf. Anybody who can hit so many bad shots and still keep playing has an answer I’ve never been able to find. Some of them lack what it takes to play good golf, but they have fun!

The privet-club professional gets about three different kinds of pupils. The largest class wants to learn without devoting much time or work to the job. If you don’t get one of this group hitting the ball well in three easy, quick lessons he reverts completely to whatever excuse for a grip, stance and swing he had before. He may even say that you taught him that way!

The second class consists of players who enjoy lessons as another challenging game. They will play ball your way and realize golf isn’t quickly mastered.

The fellows who shoot from par to 80 at your club belong to the third and smallest class. The best thing you can do for them is to diagnose their faults and let them give themselves most of the treatment, with you as a supervisor.

One of the home-club pro’s big problems is getting and trainable desirable assistants. When I get a good assistant, I spend hours teaching him how a pro shop should be run and how books should be kept. However, I must also teach him my methods of instruction, so that he will be competent in caring for members when my schedule is full. Most young men who want to be professionals prefer playing golf to teaching it. That’s natural, I did, myself but to impress upon them that around a golf club a member’s game comes first seems to be a tougher task every day.

Almost all our problems can be ironed out pretty easily; there’s even a way to avoid being put in the middle when rules disputes come up. I just show people the rules book and say to them, “The answers are there.”

Although I’m with a club in a metropolitan district, I think the pro in a smaller city has the edge on the majority of professionals at the larger clubs. In the smaller clubs, the members are proud of a pro who serves them well and does something to give their club favorable publicity.

The professional who performs competently and sincerely for the sound smaller club can be an outstanding citizen without arousing jealousy, and can do his work on a semi-social basis at his club without incurring the risks of metropolitan-district professional.

I wouldn’t trade my job for one at a smaller club. I worked at smaller clubs when I was younger, and I was treated well. Where I am now I get more headaches, but I get more money too, and more prestige. The headaches are part of the job.

For every headache I have a hundred delights. Somebody in the locker room may be beefing when I come in late some afternoon; but somebody else may be bragging that I got him out of habit of topping the ball and slicing, and he has just shot a 95 — the best game of his life.

At night I go home dead tired. The kids are in bed. My wife asks if there was a big crowd today. There was. They are paying to have fun and they’re having it. That’s great for them and for me. That’s my business.