Researchers examine nematodes and their control

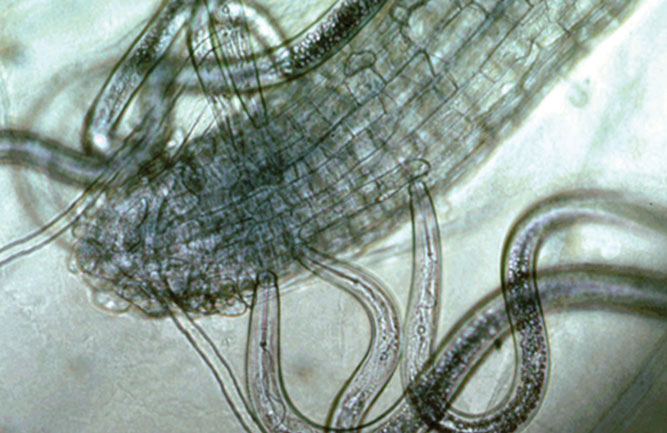

Plant-parasitic nematodes, ranging from 0.5 to 4.0 mm in length and thinner than human hair, require a live host plant to survive and complete their life cycle. They use a stylet to feed on plants by penetrating living cells, injecting digestive juices and consuming cell contents. Ectoparasitic nematodes puncture root endodermis and cortex, while endoparasitic nematodes can be migratory or sedentary within roots.

(Fig. 1) Nematodes are a concern for golf course superintendents in many parts of the U.S. and can be challenging to control. (Photo: USGA)

Nematode infestation in turfgrass leads to shortened, darker roots lacking fine feeder roots, compromising the plant’s ability to absorb nutrients and water. Cellular damage weakens the plant’s defense against soil-borne pathogens, leading to thin, weedy and necrotic turf with potential widespread loss.

This damage poses challenges on golf course greens, affecting ball roll, and may require regrassing in more severe cases. Managing nematode issues involves identifying the species causing damage to implement an appropriate control strategy.

Soil sampling methods

Proper sampling is necessary to determine if plant-parasitic nematodes are present in sufficient numbers to cause damage. When roots become inactive in winter, nematodes primarily overwinter as eggs and nematode assays will not count them.

Avoid sampling dead grass, as it will not have many live nematodes. Instead, take cores from stressed areas when the turf is actively growing. Collect an aggregate sample from an area without symptoms for comparison.

A single cup-cutter sample may give misleading results. It is better to collect 10 to 20 smaller samples — approximately 1 inch in diameter — to root depth and combine them in a sealed plastic bag to retain moisture (1).

Hand deliver or ship the samples overnight to a nematode testing lab early in the week so they can process them before the weekend. Consider using a cold pack to keep nematodes cool enough to survive. It is also essential to check with your testing lab to see if they have other requirements or recommendations for sampling.

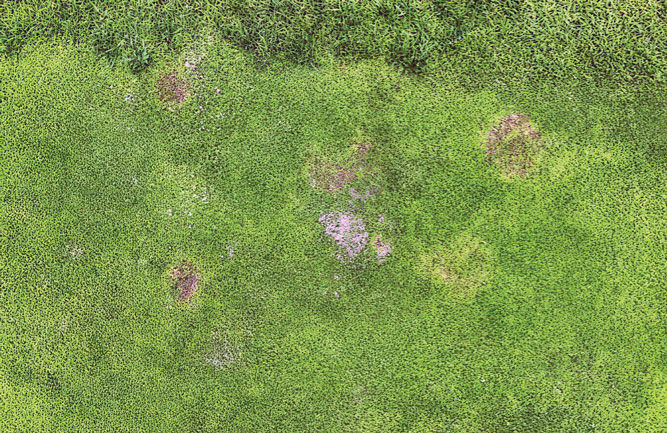

(Fig. 2) The green strip on this bermudagrass putting green was treated with fluopyram once in the fall before overseeding. In the untreated areas, there is extensive sting nematode damage. (Photo: John Rowland, Ph.D.)

Threshold levels

Utilize tolerance thresholds to identify when populations of various nematode species become problematic. Remember that these thresholds are estimates and may not account for factors like other nematodes present, turfgrass cultivar, cutting height, soil compaction, root depth and health, fertilization, time of year, growing zone or disease pressure (7). Some thresholds are established in greenhouses by inoculating sterilized soil with a specific nematode to eliminate other variables.

If your turfgrass is declining and a nematode species approaches or exceeds local thresholds, it may necessitate action. However, if you submit seasonal samples for monitoring purposes and encounter no issues with turfgrass quality, those numbers exceeding the threshold may not be a genuine cause for concern.

When uncertain, apply treatments — such as fertilizer, fungicides or nematicides — individually to small, well-defined areas. This approach allows you to assess product effectiveness, as biotic issues rarely exhibit clear boundaries. If treating on a larger scale, endeavor to leave some untreated areas for comparison.

(Fig. 3) The sting nematodes in this photo are feasting on root cells. (Photo: UC Riverside)

An initial small-scale treatment approach is beneficial if you think nematodes are responsible for turf damage at your course because it:

- Helps confirm whether nematodes are causing the issue.

- Allows testing to determine whether control products are effective.

- Prevents large applications of ineffective products.

- Can save money, time and minimize unwanted impacts.

- Allows you to dial in treatment rates before making larger applications.

Cultural management

Limiting nematode damage does not necessarily require chemical control. Cultural practices can play an essential and influential role. Here are a few suggestions to consider:

- Planting into sterilized soil and using “nematode-free” sprigs or sod gives you the best chance for success since effective nematicides are very limited, and some species are challenging to control (3).

- Proper irrigation may be the most effective way to manage light-to-moderate nematode infestations. Wilting is usually the first symptom to develop as root systems become compromised, and syringing during hot days can sometimes be enough to manage marginal nematode levels.

-

(Fig. 4) This is an example of pitting on a Poa annua putting green from stem-gall nematode damage. (Photo: John Rowland, Ph.D.)

Proper fertilization is also very important. Too much nitrogen can cause succulent growth and allow nematode numbers to rise excessively, while too little nitrogen will not be sufficient to feed the turf when its root system is compromised. Light and frequent nitrogen applications help improve turf quality even though nematode numbers may rise due to increased rooting (1).

- Foliar fertilization is more efficient when applying micronutrients — particularly when roots are compromised and soil pH is high — and can complement soil applications of nitrogen, phosphorous and potassium. Organic nitrogen derived from sewage — e.g., Milorganite — reduced sting nematodes and increased root and leaf growth (6).

- Mechanical practices like aerification and verticutting create a healthy environment for turf growth by reducing soil compaction and thatch concentration.

- Adding soil amendments that have either clay-containing colloidal phosphates or organic matter — e.g., Comand compost — increases nutrient- and water-holding capacity, which helps turfgrass tolerate nematodes (3).

- Raising mowing height also helps increase tolerance; even a slight increase on golf greens can make a visible difference.

- Overseeding can increase nematode numbers and transition problems if not properly managed. (4).

Chemical control

Nematicides may be needed when cultural practices are insufficient to manage nematode stress adequately. Chemical nematicides for use in turf are limited, and effective biological products are even scarcer. Any product claiming to be a nematicide requires an EPA registration number and approved label.

Chemical control of nematode populations is generally best done early in the year when numbers are lower. Some endoparasitic nematodes are outside roots, juveniles are more abundant, and sting nematodes are closer to the surface.

Bionematicides, such as Albaugh Specialty Products’ Zelto and Crescendo, will also typically have the most significant impact at this time (3). Nematode control programs often start with biologicals around egg hatching and chemical nematicides are applied afterward if conditions warrant.

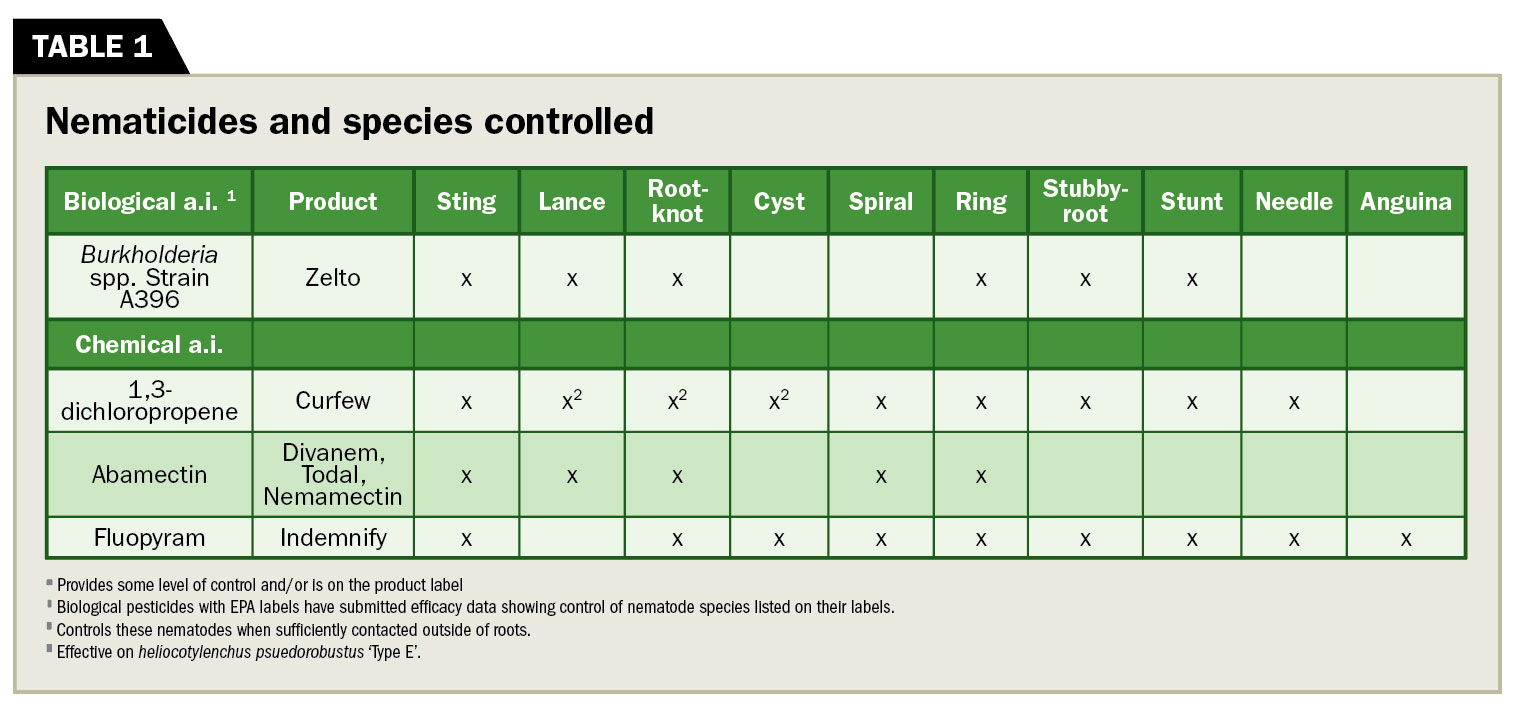

Current chemical nematicides (Table 1) contain one of these active ingredients: 1,3-dichloropropene, abamectin, fluensulfone or fluopyram, and they all belong to different chemical classes (3). Check labels for efficacy on specific nematode species and rotate products to prevent resistance.

A sound fungicide program can complement nematode control programs by reducing the chance for soil-borne diseases to enter damaged roots and infect turfgrass. Fungicides that are effective on pythium and take-all root rot are particularly beneficial.

Iprodione and thiophanate-methyl have low levels of nematicidal activity and are helpful in disease-control programs at a timing similar to biological products. Be cautious using SDHI fungicides if nematodes are an issue since fluopyram is also in Group 7 as nematicide resistance may become an issue.

Table 1

Plant-parasitic nematodes and their control

The following is a list of the primary plant-parasitic nematodes that concern golf course turf managers and recommendations for control (Table 1). Control products and strategies differ considerably depending on the nematode species, so proper sampling and identification are critical first steps in successful management.

Sting — “Sting nematodes” in the United States are typically belonolaimus longicaudatus and are considered the most damaging to turfgrass. They are native to the sandy coastal plains of the Southeast but are also currently found in Kansas, Ohio, New Jersey and Southern California, in soils containing at least 80 percent sand and less than 10 percent clay.

Lance — These semi-endoparasitic nematodes tunnel in and out of roots and are major pests of both warm- and cool-season turf. Hoplolaimus galeatus is found in the northern U.S. and is the most common species in Florida (3,12). Lance nematodes and their eggs are protected from contact nematicides when inside roots. They are most exposed just before spring greenup when bermudagrass starts to produce new roots (8).

Root-Knot — Meloidogyne spp. are in the top three most concerning significant plant-parasitic nematodes for turf, along with sting and lance. They are initially slender and motile but grow fatter as they mature. Females migrate until they find a feeding spot within a group of root cells, creating swollen roots, and then they become sedentary. Roots typically die off below infection sites and do not go much deeper than the thatch layer. The University of Florida developed a mist-extraction method for identifying these nematodes in turfgrass, but it requires a slightly different sampling method (3).

Cyst — The endoparasitic cyst nematode (heterodera spp.) is similar to root-knot nematodes and creates galls when they settle in root cells. Thresholds and control are also similar for cyst and root-knot nematodes.

Spiral — This nematode has numerous species commonly found on plants. The main criterion is that they curl into a spiral when relaxed or dead. Spiral nematodes found in the northern U.S. typically only cause droughty symptoms. However, helicotylenchus pseudorobustus ‘Type E’ can cause significant damage to Tifdwarf bermudagrass and seashore paspalum.

Stubby-Root — Found in most states and named for the damage they cause to turfgrass roots, stubby-root nematodes (nanidorus spp.) are the only plant-parasitic nematodes with a solid, curved stylet. Current nematicides are not as effective as older chemistries, and populations often rebound after fumigant applications since they can be deep in the soil (2).

Ring — Although damage from ring nematodes (criconemella spp.) is relatively rare, they are often found in damaged areas with spiral, stubby-root and stunt nematodes in the Midwest and with stunt, spiral and lance nematodes in the Northeast (8,15). Distinct rings around their body are what give them their name.

Stunt — Ectoparasitic stunt nematodes (tylenchorhynchus spp.) are mostly a problem when turf is under stress, but significant damage can occur when found with lance nematodes in northeastern putting greens (10).

Needle — Only 30 ectoparasitic needle nematodes (longidorus spp.) per 100 cubic cm of soil can prevent turfgrass seed from establishing (10). Sometimes found in finer native soil, needle nematodes can cause significant damage alone or when found with ring and lesion nematodes (9).

Stem-Gall — Anguina pacificae are found on Poa annua greens near the coast of California from the Monterey Peninsula to San Francisco on some very high-profile golf courses. Stem-gall nematodes occur at the base of the turf crown, and symptoms usually become noticeable around midsummer. Damage from these nematodes can create pits in the putting surface that greatly affect ball roll.

Summary

Correct sampling and identification of nematode populations help determine the best management practices. Use thresholds to guide and choose the best action by evaluating the situation. Sometimes, reducing stressors can be enough to manage nematode infestations.

If not, small-scale treatments can confirm whether nematodes are causing an issue and which products are effective. If nematicide treatment becomes necessary, try to rotate products to avoid developing resistance.