Insights from Great White North

The last time I visited Canada was in 1992 to see the Grateful Dead at the Copps Coliseum in Hamilton, Ontario. I haven’t had a legit reason to go see our great neighbors to the north until I heard about the Atlantic Turfgrass Conference & Trade Show going down in Moncton, New Brunswick.

The last time I visited Canada was in 1992 to see the Grateful Dead at the Copps Coliseum in Hamilton, Ontario. I haven’t had a legit reason to go see our great neighbors to the north until I heard about the Atlantic Turfgrass Conference & Trade Show going down in Moncton, New Brunswick.

And why would some greenkeeper from Delaware show an interest in visiting the Maritimes during the throes of winter? Because three of the most revolutionary thinkers in our industry today — Micah Woods, Jason Haines and Chris Tritabaugh — were all slated to present.

Short of Jerry Garcia’s ghost booking a show on the Canadian side of Niagara Falls, this conference seemed like a helluva reason to head north. So, I packed up the Titleist duffel bag I scored at the member/guest last year and boarded an Embraer 175. Destination: Moncton.

The conventional guidelines are broken

“The conventional soil guidelines did not consider the cost of fertilizer very important because golf courses have plenty of money, apparently.” —Micah Woods

Micah Woods, Ph.D., literally was born into golf. The first year of his life was spent in an RV cruising across Canada with his family as his father chased the Canadian golf tour. Although his father didn’t make it as a touring professional, he passed his love of the game to his son.

Today Woods is chief scientist at the Asian Turfgrass Center in Bangkok, Thailand. The turf industry would be pretty dull without Woods’ logical and thoughtful input, and who knows where soil nutrition would be if his dad had hooked him up with a Louisville Slugger instead of a set of blades.

The conventional nutritional guidelines for turfgrass were developed in the 1960s and ’70s, based on forage crops like corn. People figured if the recommended nutrient levels were good for growing corn, they must be cool for growing turf. While forage crops are for the most part profitable, they really couldn’t figure out how to place a value on turfgrass. So, the developers of these arbitrary guidelines deliberately placed high targets on the nutritional values for growing turf without regard to costs.

In 2006, Woods began the process of improving the guidelines with the help of Larry Stowell, Ph.D., co-owner and co-founder of Pace Turf. They determined the conventional guidelines were way too high, but the numbers they came up with, although much lower, seemed arbitrary as well.

It then dawned on them (more so Stowell than Woods, according to Woods) they had this data set of soil conditions producing adequate surfaces. They immediately began studying this data to determine the minimal amount of nutrients needed to produce good turf. After six years of collecting data, they agreed on some palpable numbers, and the Minimal Levels of Sustainable Nutrition (MLSN) were born.

“I thought we’d get laughed out of the room by scientists because they would say, ‘You can’t do soil interpretation that way,’” Woods says about when MLSN was first published. “But the traditional target levels are just wrong and too high, so MLSN was designed to fix these problems and to provide a modern fertilizer recommendation for turfgrass anywhere in the world based on modern soils, modern turf varieties and the modern turf management practices we use today.”

In Micah Woods’ travels throughout the world, he’s seen interesting fertilizer applications, such as the one shown here on a golf course in Vietnam.

The matrix

“This is your last chance. After this, there is no turning back. You take the blue pill — the story ends, you wake up in your bed and believe whatever you want to believe. You take the red pill — you stay in Wonderland and I show you how deep the rabbit-hole goes.” —Morpheus, The Matrix

Jason Haines took the red pill, and probably was the first greenkeeper to implement MLSN guidelines into a modern fertility program.

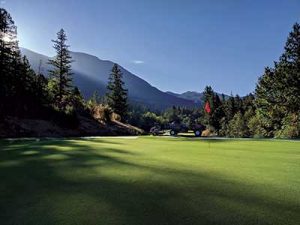

Haines is a superintendent who grows (kills) grass at Pender Harbour Golf Club, located on the Sunshine Coast of British Columbia. This Canuck has been bombarding our industry with revolutionary ideas “aboot” managing grass since 2012.

When superintendents in his area faced a pesticide ban, the majority tried to fight it. Haines had a different take.

“Everyone was putting all their efforts into stopping the ban,” he explained, “but no one was thinking about what we were going to do if the ban actually happened. So, from that point forward, every decision I made took into account my end goal of reducing pesticide use.”

This is why I was so pumped to meet this guy, because who the hell thinks this way? If the hippies in my state ever decide to organize and demand that golf courses ban pesticides, I’m not sure I have the courage to go Haines style. In all likelihood, I join the jerks battling the ban.

Although the Great Recession hit the states in ’08, the folks at Pender Harbour really didn’t feel the sting until 2010. Realizing the times, they were a-changing, Haines cruised the web searching for ideas to spend less dough and stumbled upon Woods and Larry Stowell’s newly developed guidelines, which claimed to be a “more sustainable approach to managing soil nutrient levels that can help you decrease fertilizer inputs and costs, while still maintaining desired turf quality and playability.”

“I was all in,” Haines gushes. “MLSN seemed simple, and if it didn’t work, I would go back to the old way.”

The cost savings were immediate, but something else happened that was unexpected.

“It seemed like the less fertilizer I applied, the better the turf responded. It’s one of those things that seem too good to be true, and I didn’t believe it until I saw it.”

It was a revelation, and he opined that perhaps there was more to applying less fertilizer than simply saving money. Maybe, Haines hypothesized, the past problems he’d seen — disease and weeds — were caused by applying too much fertilizer.

Describing himself as “super curious and too obsessed” to wait for someone else to figure out all this, Haines went to work.

The first thing he noticed was a huge reduction in weeds. Prior to implementing MLSN, postemergent herbicides were a big part of his program. But when he stopped applying potassium on his tees and fairways — because the K levels in his soils were way above the MLSN guidelines — weeds like clover and dandelion vanished.

“We still get the odd dandelion popping up,” he says, “but instead of spraying herbicides to get rid of them, I just tee up a Titleist on top of one and blast it with a wedge.”

In his quest to battle the pesticide ban “his way,” Haines basically stopped applying pesticides to see what would happen. He observed that growth rate might influence disease pressure. For example, when growth was high, he recognized more disease. But when the growth rate slowed, there was less disease.

“If I had applied a fungicide,” Haines explained, “I would’ve learned nothing.” Haines currently uses MLSN to determine his fertilizer use but describes it as “boring.” “It’s easy to get your nutrients right in the soil,” he says.

He’s also been labeled a minimalist but prefers to describe what he’s doing as “precision turf management.”

“I’m not using less to use less,” Haines states, “I’m using less because in the past I used too much. I try to figure out the right amount and apply that amount.”

Haines also thinks it’s cool to be poor. He sees his low budget as an opportunity to see what’s possible. His focus today is trying to eliminate all the guessing we do as turf managers.

“If we can figure out where we are guessing and guess less,” he says, “we might be able to seriously reduce that margin of error.”

In Japan, clippings are collected in this fairway mower outfitted with a vacuum.

Nutrient deficiencies: Avoidable disasters

“I tend to think of things in extremes. I sometimes find it useful to take a thought and go all the way to the extreme in one direction, and all the way to the extreme in the other direction, recognizing in reality what we’re trying to do is somewhere in between. But if we can understand the implications of taking that thought all the way to the extreme, it helps us clarify what is the reasonable thing to do.” —Micah Woods

Our goals with fertilizers are very simple. They are to supply the grass with what it can use while preventing nutrient deficiencies in an effort to grow good grass.

Applying no fertilizer while expecting the soil to supply all the nutrients required to grow healthy turf would be considered an extreme. Another extreme would be to totally disregard what is in the soil and apply 100 percent of what the soil can use. For years our industry has leaned toward this second extreme by ignoring what is in the soil and over-fertilizing. We never asked ourselves two logical questions, posed by Micah Woods:

1. Is this element required as fertilizer?

2. If it is required, how much should I apply?

The answers to these two questions lies in the middle of the two extremes, thus clarifying our goals with fertilizers.

Woods explains that “it’s too risky to assume the soil can supply everything, while it’s silly and a waste of time and money to assume the soil can supply nothing. MLSN lets us find the perfect spot in between those two extremes to produce excellent turf, supplied with just the right amount of nutrients, with no risk of nutrient deficiencies.”

‘M’ stands for minimum

One of the biggest errors greenkeepers make with MLSN guidelines is assuming the numbers are targets. Unlike traditional soil testing — where values are classified as low, optimum or high — MLSN represents the minimal amount valued in parts per million. For example, when you receive results from a soil test and the calcium level is 828 ppm, this is well above the minimum of 331 ppm of the MLSN guidelines. Is this element required as fertilizer? No.

But if those calcium levels are 280 ppm, you would be at a deficit, so this element would be required as fertilizer. Even if a soil test comes back right on the number of 331 ppm, you better fire up the Vicon, because that reserve will need to be replenished. The plant is going to use what’s there (it is available!), because the last thing you want is a nutrient deficiency. Those are avoidable disasters.

MLSN really is this simple. It eliminates the guesswork along with the burden of trying to balance everything going on beneath our feet. MLSN can be implemented on any grass type or soil type and will work just as well on Poa annua greens in California as it does on zoysia fairways in Japan. What MLSN has done is repair the old and broken conventional guidelines and give turf managers around the globe a more logical approach to interpreting soil data.

Photos: Jason Haines (1); Micah Woods (2, 3)