Course of the Week: Heritage Links directs logistic, mid-pandemic ‘triumph’ at PGA West

In the spring of 2021, when the team of course-construction experts from Heritage Links arrived here at PGA West, the primary object of their planning had been the regrassing of greens on the Arnold Palmer Private Course, one of nine layouts located at the nation’s most sprawling golf-real estate development.

The process of regrassing, anywhere in North America, must adhere to a construction schedule borne of seasonal, agronomic realities. In the desert, however, those realities are stricter and condensed. As in Florida, desert work only begins when snowbirds depart and must be concluded before they return. Yet newly regrassed greens must confirm to another, narrower deadline: They must be planted and established before overseeding is undertaken in late September.

Members involved in the regrassing renovation at PGA West discuss construction plans. (Photo: Heritage Links)

“The regrassing must be finished by the beginning of July to have a chance at a proper growing season, before all the superintendents overseed,” Oscar Rodriguez, vice president at Houston-based Heritage Links, a division of Lexicon, Inc., said. “You need at least 90 days of growth in order not to lose the base plant. Therefore, the challenge is completing everything else you have planned for those greens and surrounds before you regrass. This includes all the shaping, irrigation, fumigation and surface finish shaping.”

“We had a very busy schedule on the Palmer Private last spring. But just as we started, the client came to us and said, ‘Oh, can you regrass the Norman Course greens, as well?’ Back to the drawing board! Bottom line: We did regrass all 39 greens at both courses on July 7, 8 and 9,” Rodriguez said. “We got it all done and done right. In this climate you can’t just work harder or longer, you need more resources and a solid game plan.”

“That was only a year removed from the whole world shutting down. We were still in the midst of all that uncertainty,” Brandon Johnson, architect at the Arnold Palmer Design Company, said. “And that was a job with a lot of moving parts. Heritage kept it all on track. They were so organized and flexible and resourceful. They had to be, in order to pull it all together.”

“During that more serious stage of the pandemic, it was like, ‘Can we really do all this?’ There were supply chain issues and labor issues. And it was so hot! The Basamid having to go down in that specific window put such pressure on all of us,” Johnson said. “That’s what I mean about flexibility: scheduling around irrigation heads that don’t show up. Or the grass, which was coming all the way from Georgia. Pretty amazing. Logistically, I’d call it a triumph.”

Opened for play in 1986, the Palmer Private Course had been due for a refresh, according to Chris May, director of agronomy for all nine courses at PGA West. That reality informed the decision to regrass all 18 greens with TifEagle during the summer of 2021, in addition to restoring those putting surfaces to their original footprints, renovating every bunker on the course (after restoring them to their original shapes), and addressing specific irrigation issues.

“The current owner is a golf fanatic and he wants this place to be PGA West the way it used to be in the 1980s and 1990s,” May said. “So, that desire did inform the work Heritage executed for us last year, about $1.5 million worth. It was really sort of a face-lift. We may go deeper as time goes on.”

The Heritage Links crew working on restoring the Arnold Palmer Private Course. (Photo: Heritage Links)

May and the ownership at PGA West were extremely clear: On the Palmer Private, this was to be a restoration, not a renovation. That decision required the design and construction teams to first determine what was original and what exactly should be restored.

“Our project superintendents Mark Maldonado and Sergio Cadengo were our two guys on the ground at PGA West,” Rodriguez said. “Back in the day, course-builders dropped a metal interface in the ground to mark the underground green perimeter, during construction. They installed it so that future course renovation efforts could determine where the original perimeter was located. And we did find them on the Palmer Private: Those green edges had all migrated between two and 12 feet!”

“Builders eventually moved from the metal interface to a hard-plastic interface, 40 millimeters thick. Then some agronomists wanted to move away from that: They wanted a tracer wire where we put a pulse through to find the original outlines of a green. But here at PGA West, we went Old School: Mark and Sergio went in and found the metal interfaces,” Rodriguez said.

Just one problem with that, according to May: Some of those metal interfaces had rotted away. What’s more, bunkers are not typically built with subterranean perimeter markers — they certainly weren’t constructed that way during the 1980s. It was here that a canny bit of next-generation technology took over.

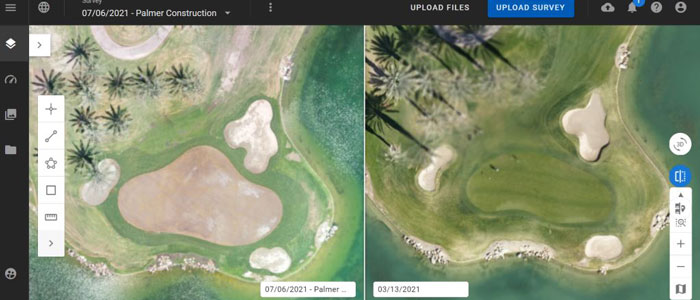

As a first step, Chris May was able to find age-appropriate aerial photography of the Palmer Private Course. But mere photos were not enough to guide a meticulous restoration/reconstruction effort like this one. For that level of detail, May deployed a cloud-based, drone photogrammetry tool.

“This was really Chris’ baby,” Rodriguez said, referring to RDOai, a data management platform that stores, processes, and analyzes survey data, then enables the user to share that data across platforms. “The old aerials provided a guideline, but Chris then had the whole property shot with RDOai. We outlined the aerials and digitized them, converting them to CAD. With the new files, Sergio could essentially lay Brandon’s drawings over the imagery. We then created documents and took them to the field with sub-centimeter accuracy. Basically, we laid out the new golf design dimensions and surveyed them in place.”

A look at the property using the RDOai technology. (Photo: Heritage Links)

Johnson said this mapping provides an extraordinary window on a course’s past, present and future.

“Matching up the old photography really helped inform the project, especially at the beginning, in terms of what was there before things morphed and changed,” Johnson said. “The ability to fly the property and get everything linked up — not just design elements but irrigation — was great. As far as mapping, it’s what we based everything off.”

“So, it showed us how things were, in context. But here’s what’s really cool: As we change things, now we’ve got this historical record of all that. After finding the original green edges, we did push and tug them. But in reestablishing those edges, we have an accurate record of all information going forward,” Johnson said. “For the first time in history, we have the ability to document down to the millimeter what is on the ground now. We have the ability to put things back and track modifications with such great accuracy. Interpolating old, grainy aerials isn’t exactly optimal. With this technology, the guess work goes away.”

“We wanted to bring the Palmer Private Course back to the way it was and, in that respect, this [RDOai] was a great design and construction tool,” May said. “It’s a storage platform basically. It allows us to collect all our drone images and make annotations and drawings on top. The [PGA] Tour introduced us to this technology, and it’s a practical way to catalog nine separate golf courses — and compare how a green looks today compared to 1995.”

“But this tool plus the drones, for us, is the future. We can spot so many issues with it,” May said, sharing his screen, stopping on a specific Norman Course fairway, and using his cursor to point out a small discolored area. “See that: That’s a sprinkler head that’s jammed up with something. We’ll fix that. We can also use this to identify and deal with high traffic areas — then we can send shapes [.shp files produced by the RDOai platform] to the Yamaha platform to keep carts out of a certain area. Robotic mowers work on shapefiles, too. You can see how many ways this is applicable to daily maintenance. I mean, these images are live! Google images can be 2-3 years old. This is today.”

A look at the project using the RDOai. (Photo: Heritage Links)

During the COVID spring and summer of 2021, May indicated that it’s unlikely his team, the Heritage team, Johnson and all the project vendors could have met all the short deadlines — not without the online ability to map, design and plan in real-time.

“It sure helped,” May said. “Before, we’d have all been in the field, marked it all, surveyed it into AutoCad, then let someone else see it. When COVID meant we couldn’t travel, this allowed us to meet online, to conference and make decisions, then let the architect play with it.”

According to May, the imaging capability “helped us determine very quickly how much area we were adding, how much sod to buy, how many sprinklers to buy. It also helped us communicate with the owner, to share with him exactly what we were proposing. Pictures are worth a thousand words.”

All of this planning and prep — some of it executed well in advance; some of it on the fly — served as a prelude to the exercise undertaken the second week in July. That’s when Cadengo, Maldonado and their respective Palmer and Norman course crews regrassed all 39 greens — meeting the deadline and leaving the requisite 90-day grow-in period intact.

Construction in full swing at PGA West. (Photo: Heritage Links)

Everything on both courses revolved around enabling this specific process to take place July 7-9, 2021. Not merely the shipping of TifEagle cross-country from Georgia, during a pandemic. Not merely the fumigating of all 39 greens via the Basamid process. Everything had to be completed on the detailed timeline ahead of regrassing — or after regrassing.

“If you look at the logistics — at exactly where the Norman course is located, and where the Palmer Private course is located — naturally they are at opposite ends of a massive property, with a whole lot of real estate in between,” Rodriguez said. “As a consequence, we really had to staff and coordinate two distinct groups, one for each course project. And within each group, we had several crews handling demolition, bunkers, irrigation, and greens work. All I know is, we were everywhere on that property from April through July.”

There were plenty of projects on both courses that had nothing to do with the regrassing of 39 greens. On the Norman course, for example, Heritage dealt with several existing access and egress issues. The original cart paths there had not been positioned directly along the fairway’s edges; a great deal of landscaping had instead been created in between. “Over time, that concept didn’t work out, so we mitigated that situation by creating access/egress points along each fairway,” Rodriguez said. This project, along with the swapping of old sand for new in all the Norman Course bunkers, were among the post-regrassing priorities.

Construction taking place along the river at PGA West. (Photo: Heritage Links)

“You can’t even begin to get your head around the logistics if you don’t work backward from the regrassing,” Rodriguez said. “That is the fulcrum of a project like this one. Every detail must be considered according to that deadline. For example, in the 1980s, when the Palmer Private Course was built, the irrigation heads were controlled on a block system: One valve controlled 5-10 heads. Because we improved the contours in the green surrounds, it made sense to go back in there and update the irrigation as well — with part-circles that provide better, more efficient water coverage around all the greens. That happened before July.”

“However, there are four Palmer holes, 14 through 17, that all run along a Coachella Valley Water District canal. Naturally, those holes required a bit more environmental concern. Any disturbance there had to protect that canal,” Rodriguez said. “So, we sodded everything around the greens there, to protect against any erosion. Everything greens-related was scheduled ahead of July. Everything else, after July.”