Compost amendments on the golf course

Compost application on an approach to a putting green. (Photo: Pete Landschoot)

If you are a golf course superintendent struggling with poor or marginal soils, compost amendments may provide some relief.

A good-quality compost can improve structure in soils with a high amount of clay, reduce compaction and increase infiltration.

Amending compost into sandy soils can add nutrients, improve water and nutrient retention and increase soil microbial activity. If done correctly, amending compost into poor soils should result in better turf performance and may save on fertilizer and irrigation costs.

Compost availability has increased in recent years because of more production facilities coming online in areas where golf courses are concentrated. Depending on your location, compost may be less expensive than a good-quality topsoil.

When considering how much to purchase, consider that compost can have a stronger soil-modifying effect than equal or greater amounts of topsoil. However, before jumping on the compost bandwagon, realize that application and incorporation of compost into soil is labor intensive and time consuming, so carefully consider where to use it and where not to use it. Also, become familiar with the basics of choosing a quality product. Finally, know how much to apply and how to incorporate compost into soil.

Where to use compost

A good-quality compost should resemble a dark potting soil and have a light, crumbly structure. (Photo: Pete Landschoot)

Areas of your property with poor or marginal soils or those that receive high amounts of traffic are good candidates for compost applications. These could include cart paths, tees, approaches to greens and fairway areas where topsoil is thin. Typically, we don’t use composts for putting green soils because they can contain higher amounts of mineral matter than sphagnum or reed sedge peats and may not be as resistant to decomposition (i.e., not as stable).

If you’ve never used compost as a soil amendment, start with a relatively small area such as an approach to a green or the clubhouse lawn to gain experience with application equipment and methods of incorporation. Once you have had a chance to evaluate the results of your applications, you can move on to larger projects.

Choosing the right compost

Not all compost products are alike. Composts are made from source materials, including yard trimmings (leaves and grass clippings), biosolids, animal manures, food residual and other organic byproducts. Product quality can vary depending on how it is composted and stored.

Because of quality concerns, it’s essential to have some basis for evaluating suitability of compost products for use on golf turf. Ideally, the product has been field tested or routinely used by other turf managers. If possible, visit the compost facility, take a sample and examine it for unwanted objects and unusual or offensive odors. Also, check the compost piles for the presence of weeds. If weeds are growing in the compost, there’s a good chance weed seeds will be present as well. Ask the facility manager for a chemical and physical lab analysis of the compost. Compost manufacturers who test their products on a regular basis are better able to monitor quality and uniformity from batch to batch.

The following are general guidelines for determining the suitability of compost for use on golf turf. Some of these are field tests you can perform on your own, whereas others require a lab test.

Topdressing units with large hoppers, belts and brushes mounted in the rear are preferred for surface applications. (Photo: Pete Landschoot)

Visual appearance. A good-quality compost resembles a dark potting soil and has a light, crumbly structure. It should be screened to 0.375 inch or 0.5 inch and be free of large stones, wood pieces, plastic and glass.

Odor. Most composts have a pleasant, “earthy” aroma, similar to a forest after a rain. Some biosolids and animal manure-based products initially have strong musty odors, but this usually dissipates a couple of days after application. Avoid composts with strong ammonium or sulfur odors, as this may indicate an unfinished product.

Moisture content. Research at Penn State has shown that the moisture content of compost influences quality and uniformity of application. Typically, composts with moisture contents between 30 percent and 50 percent are suitable for spreading and soil incorporation. Wet composts (greater than 60 percent moisture content) tend to form clumps and balls, are difficult to spread evenly on turf surfaces and mix poorly with soil. Also, wet composts are heavy, difficult to handle and can smear into turf and pavement. If you squeeze a handful of compost and water drains out, it’s generally too wet to apply.

Dry composts (less than 20 percent moisture content) tend to produce excessive dust, which may accumulate on windows, buildings and vehicles. Dust may be hazardous if inhaled or if it enters the applicator’s eyes. Dry composts also are difficult to work into soil, forcing equipment operators to spend more time and effort tilling the soil.

Organic matter content. Composts can vary widely in organic matter content. Our research has shown that composts containing more than 60 percent organic matter on a dry-weight basis tend to be the best soil amendments. You can determine organic matter by a lab test, but most test procedures consider everything combustible in a furnace as organic and do not distinguish among humus, wood chips, bark and plastic. So, a visual examination of the compost must be part of the evaluation.

Carbon-to-nitrogen ratio. Soil-test labs typically report a value that indicates the ratio of carbon (C) relative to the amount of nitrogen (N) in compost, often reported as C:N. This ratio is an important indicator of the plant-available nitrogen in compost. If the C:N is above 30:1, soil microorganisms can “tie up” or immobilize nitrogen, making it unavailable to turf. If the C:N is 30:1 or less, turfgrasses can use the nitrogen in compost.

Compost being tilled into soil using a rototiller. (Photo: Pete Landschoot)

pH and nutrients. A desirable pH range for compost is 6.0 to 7.5. Although a compost with a pH value a little outside this range may be acceptable for use on a golf course, extremes in pH may reduce nutrient availability or cause toxicity in turfgrasses. In an establishment study at Penn State, a manure-based compost with a pH of 8.5 tilled into a clay-loam soil caused seedling inhibition, probably because of ammonia or ammonium toxicity.

Nutrient content of composts is low when compared with most golf turf fertilizers. However, because composts are used mostly as soil amendments, relatively large amounts are applied in a single application, increasing the nutrient load to turf. Surface applications of 0.25 inch of compost typically elicit a turf green-up response from nitrogen and other nutrients. A 1-inch or 2-inch layer of compost tilled into a soil prior to establishment can supply all the nutrients required by turf for a year or more. A recent study at Penn State showed a nutrient response in turf lasting five years from a 2-inch layer of yard-trimmings compost tilled into silt-loam soil.

Soluble salts. Excessive soluble salts sometimes are present in compost made with animal manures. High concentrations of soluble salts can injure turf by restricting absorption of water, and in extreme cases through ion toxicity. Unfortunately, it can be difficult to determine if a certain concentration of salt will injure turf because injury potential depends on the type of salt, salt tolerance of the turf species and the method of application. If you suspect high soluble salts in a compost, check with a lab that analyzes soluble salts and ask for advice.

Application methods

Surface applications. Surface application of compost is a means of gradually incorporating organic matter into soil over a period of three to five years. It’s typically accomplished by light topdressings of compost following core aeration. Surface application of a 0.25-inch layer of compost is easily worked into aeration holes and mixed with soil cores by dragging or slicing with a disc seeder or verticutting equipment. The key to successful surface applications is to obtain good incorporation and mixing with soil. Simply depositing compost on the surface with no incorporation will result in an organic layer on the surface that can lead to excess water retention and shallow rooting.

Because compost is light and bulky, topdressing units with large hoppers, belts and brushes mounted in the rear are preferred for surface applications. We have successfully used slicing equipment to break up cores and drag mats to mix the compost with soil. Dragging also helps to move compost into holes created by core aerators.

Recent research results from a large-surface application trial showed that four years of applying annual applications of 0.25 inch of a yard-trimmings compost (60 percent organic matter) showed an increase in organic matter of 1.5 percent.

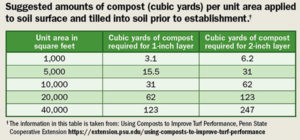

Tilling compost into soil before establishing turf. Another means of compost incorporation is rototilling into soil. You may use this method when establishing turf on bare soil. It provides an excellent opportunity to immediately improve soil structure and increase organic matter content. The most effective method of tilling compost into soil involves stripping sod from the surface, followed by an initial tilling to loosen the soil, then spreading a 1-inch to 2-inch layer (approximately 3.1 to 6.2 cubic yards per 1,000 ft²) of compost on the soil surface and tilling to a depth of 4 to 6 inches (Figure 4). Check to make sure the compost is adequately mixed with the soil and not distributed in a layer at the surface before curtailing tilling. If not thoroughly mixed, large clumps of compost and soil will remain and result in variable soil conditions and turf growth.

The rate of compost you use depends on the compost and soil conditions. Composts with higher percentages of organic matter and nutrients will provide the greatest soil improvement. Lower rates are better suited for soils that need only limited improvement, whereas higher rates are good for poor soils (very sandy soils, clay soils or shallow topsoil low in organic matter). In research trials, we found that more than 2 inches of compost may be difficult to mix thoroughly 4 to 6 inches into the soil. Some soil test labs provide specific recommendations for rates of compost based on the organic matter content of the soil.

Although compost tends to decompose faster than sphagnum or reed sedge peats, the benefits of tilling compost into soil should last for many years. Research at Penn State revealed a 2-inch layer of yard-trimmings compost with 60 percent organic matter tilled into a silt-loam soil increased organic matter 3 percent compared to a nonamended control soil after five years.

If soil problems are limiting turf performance, consider the addition of compost as a long-term solution.

Can you recommend a couple of companies who work with compost to improve nutrient levels in sandy golf fairways?