A new key to Poa annua seedhead suppression

Research shows an early application of Proxy (ethephon) provides consistent Poa annua seedhead suppression.

Annual bluegrass (Poa annua) seedhead suppression long has been among the more unpredictable turf management objectives faced by superintendents. One challenge is that annual bluegrass is one of the most adaptable plant species on the planet, leading to a broad range of genetic diversity spanning geography and management intensity.

In addition, several interacting factors contribute to stimulate floral primordia. Embark T&O (mefluidide) is an established seedhead suppressor, generally considered to suppress seedheads better with increasing rates. Embark at effective rates (1 fl. oz. /1,000 sq. ft.), however, injures both annual bluegrass and creeping bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera). Adding chelated iron can decrease turf discoloration by Embark, but the tank mixture tends to promote Embark precipitation, lowering product efficacy when the two products are applied together.

A recent decision by the 3M Co. to reduce waste in the manufacturing of a common spray adhesive has nearly eliminated the availability of mefluidide, a waste product in the manufacturing process and the active ingredient in Embark. Efforts to manufacture mefluidide directly are said to be cost prohibitive. Thus, this long-standing seedhead suppressor’s availability has been limited in recent years and may be phased out completely.

Enter Proxy (ethephon)

Proxy (ethephon) first was marketed for seedhead suppression in turf about 15 years ago and generally offers improved turf safety over Embark. As with most products, the safety of Proxy on creeping bentgrass and annual bluegrass turf is not absolute. In warmer climates or warmer times of the year, Proxy can cause “crown rising” of creeping bentgrass that leads to scalping-associated discoloration on greens. In northern climates, applying Proxy during late spring, especially on thatchy greens, likely will cause the crown-rising problem to appear in early summer. In the Deep South, Proxy has been associated with severe declines in turf quality and root density of creeping bentgrass.

The reason for root loss in hot climates is unknown, but recent research at Virginia Tech suggests Proxy may accentuate root senescence following turf stress. In a trial conducted on four Virginia putting greens, Proxy at 5 fl. oz. /1,000 sq. ft., when mixed with PoaCure (methiozolin), interacted with core aeration stress to cause creeping bentgrass stand loss. Treatments were applied at 50 growing degree days at a 50-degree F base temperature (GDD50) (March 2012, April 2013 and 2014) and repeated three weeks later. PoaCure alone did not injure creeping bentgrass at any rate, but when mixed with Proxy on greens that were aerated a few days after treatment, up to 90-percent creeping bentgrass stand loss was observed at the 2.4 fl. oz. /1,000 sq. ft. (4 X) PoaCure rate. When core aeration was separated from chemical treatments by at least two weeks, creeping bentgrass was not injured by any treatment.

The theory has not yet been confirmed, but it seems that aeration stress interacted with Proxy to cause root loss that could not be replenished by creeping bentgrass crowns in the presence of PoaCure. PoaCure can inhibit root growth when root tips are exposed to the product, a situation that normally would not occur on a green unless severe stress caused root loss, requiring new root growth from turfgrass crowns.

If Proxy were causing root loss following aeration stress on greens we normally would not notice symptoms on a well-irrigated green, as creeping bentgrass can replenish roots quickly in cool weather. Therefore, don’t mix PoaCure with Proxy, especially if you expect mechanical or environmental stress on greens. Proxy also tends to cause transient yellow-to-orange discoloration of annual bluegrass, especially when spring weather presents intermittent frost events. Primo Maxx (trinexapac ethyl) typically is mixed with Proxy to improve both turf density and color. When applied in spring in the Transition Zone and further north, this combination of Proxy and Primo Maxx is extremely safe on putting greens but tends to deliver highly variable annual bluegrass seedhead suppression among locations and years.

In an analysis of 195 observations from published reports, Proxy suppressed seedheads 56 percent on average, with a standard deviation of 28 percent across 11 Northeastern or Northcentral U.S. trials. In 21 replicated research trials conducted in Virginia in the past 15 years, seedhead suppression provided by Proxy applied in the spring also has been similarly variable. These data suggest that superintendents can expect about 70 percent of Proxy applications to reduce seedhead cover between 28 percent and 84 percent compared to nontreated turf.

We have tried almost everything in the book at Virginia Tech to reduce this variable seedhead suppression by Proxy. We quickly recognized, like others, the value of proper application timing and have successfully employed growing degree day application thresholds based on both 32 and 50 F base temperatures. In the Mid-Atlantic region, applying Proxy at 50 GDD50 or 400 GDD32 (base 32 F) typically maximizes efficacy. We even have used black sand to “heat up” the green. We were able to rapidly initiate annual bluegrass seedhead emergence using black sand, and this allowed our Proxy applications to be timed precisely relative to seedhead emergence. The result was still poor seedhead suppression in the first four weeks of the season. After much experience, it became apparent that all of our application timing research only served to optimize what was Proxy’s inherently variable seedhead suppression.

Why the variability?

What’s the source of the variability? Could it be Poa annua’s genetic diversity, as many have proposed? No. Despite similar trial conditions and applications timings, Proxy would work great one year at a given location but not at the next. Although genetics probably plays an important role, it can’t explain all of the variability.

The term “flowering” is loosely used and involves photoperiodic induction, floral evocation and floral differentiation. The photoperiod-based induction process is fairly well studied, but the process of evocation and differentiation is far less understood. Chemical compounds yet to be discovered and labeled as “florigenic stimuli” or “florigens” are believed to travel through the plant using nutrient-conducting tissue to kickstart floral evocation at the growing point. Hormones, similarly translocated, are believed to play a role in the floral differentiation stage. Because the production and translocation of chemical stimuli for floral initiation are influenced by environmental conditions, it stands to reason that a high percentage of annual bluegrass plants will “initiate seedhead formation” during warm periods in winter. Spring-applied Proxy will not prevent seedheads on these plants if floral differentiation has already begun.

About five years ago, I started evaluating “early” applications of Proxy in winter and fall to test a hypothesis that these winter-initiated floral primordia could be prevented. The results were astounding. In 51 side-by-side comparisons within 13 field trials at various Virginia golf courses, the normal spring program of Proxy at 5 fl. oz./1,000 sq. ft. plus Primo Maxx at 0.125 fl. oz./1,000 sq. ft. suppressed seedheads 58 percent, with a standard deviation of 17 percent. When an early application was included with a normal spring program, seedhead suppression was improved to 95 percent with a standard deviation of 5 percent in these same trials.

Data from nontreated turf shows that the duration of Poa annua seedhead production at Spotswood Country Club in Harrisonburg, Va., was about 80 days in 2012. We often see the spring Proxy plus Primo Maxx program perform inconsistently during the first four weeks of the spring season, but seedhead suppression generally improves later in the season after the second application.

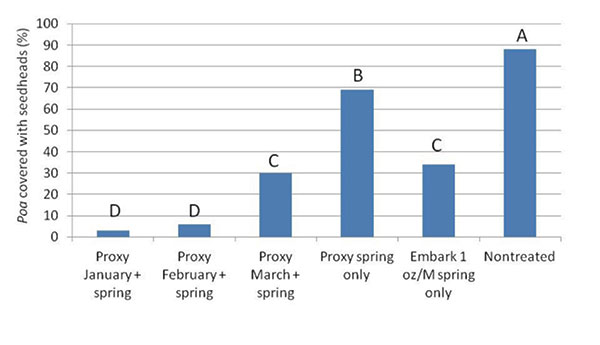

Figure 1Percentage of annual bluegrass displaying seedheads at peak bloom six weeks after 50 GDD50 averaged over putting green trials in Blacksburg and Harrisonburg, Va., in 2012. Proxy at 5 fl. oz./1,000 sq. ft. was applied at various winter timings and followed by the spring program of Proxy at 5 fl. oz./1,000 sq. ft. plus Primo Maxx at 0.125 fl. oz./1,000 sq. ft. twice at a three-week interval.

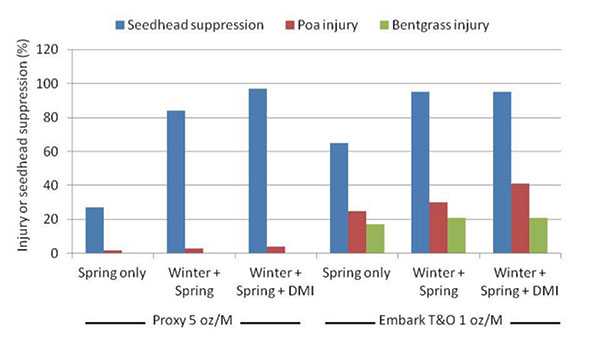

Applying Proxy at 5 fl. oz./1,000 sq. ft. at least one month prior to the normal spring GDD-based program of Proxy at 5 fl. oz./1,000 sq. ft. plus Primo Maxx at 0.125 fl. oz./1,000 sq. ft. nearly eliminates seedhead production in most cases (Figures 1, 2, 3). Winter application timing did not strongly influence performance if Proxy was applied at least one month before the spring GDD-based treatments, which was late March in 2012 (Figure 1). Proxy always was safer to both annual bluegrass and creeping bentgrass compared to mefluidide (Figure 2).

Figure 2Influence of Proxy plus Primo Maxx or Embark T&O spring programs (Spring) ± a February early application of Proxy or Embark (Winter) ± a 90 GDD50 treatment of Bayleton at 1 fl. oz. /1000 sq. ft. (DMI) on creeping bentgrass and Poa annua injury and suppression of peak Poa annua seedhead production averaged over putting green trials in Blacksburg, Va., (2011) and Harrisonburg, VA (2012).

Another concern

A particular concern with fall or winter Proxy applications is the potential effect additional Proxy applications may have on Poa annua winter survival in the extreme north. Our research in Virginia can’t directly answer this question, but we can say that these Proxy programs have not reduced Poa annua cover and were considerably safer on Poa annua than Embark programs in every evaluation. Recent research is proving that fall Proxy treatments applied between mid-November and mid-December work equal to or better than winter treatments to improve efficacy for seedhead suppression (Figure 3). Fall applications are much easier to implement than winter applications because of seasonal weather patterns and lack of snow cover in most locations. Proxy applications prior to Nov. 15 are not advised in our area, as seedhead suppression was reduced in research trials.

Figure 3Virginia Tech graduate student Sandeep Rana collecting spectral reflectance data on seedhead suppression studies. The plot to Rana’s left is a spring-only program of Proxy plus Primo Maxx that suppressed seedheads about 60 percent. Surrounding plots included fall or winter applications of Proxy in addition to the spring program, improving seedhead suppression to over 90 percent.

Our current recommendation for Mid-Atlantic states is to apply Proxy alone in late November or December and follow with Proxy plus Primo Maxx in spring using 400 GDD32 or 50 GDD50 as the initial spring trigger, and repeating the mixture 3 to 4 weeks later. This program works great in areas where greens tend to enter winter dormancy soon after the fall treatment, as these fall treatments can increase winter-associated leaf tip burn and decrease new leaf growth that would otherwise mask frost injury.

Use of a pigment-containing product has improved winter turf quality in several of our trials and may be appropriate for southern or coastal locations where greens do not go completely dormant. We also have evaluated these winter and fall applications with Helena’s ethephon product, Oskie, with the same response. Both Proxy and Oskie programs exhibited dramatically improved seedhead suppression when a fall or winter treatment was applied in advance of a normal spring two-application program. In collaboration with Adam Van Dyke (owner, Professional Turfgrass Solutions, LLC) in the past two years, we have evaluated early applications of these two products in both fall and winter with multiple trials conducted in Virginia and Utah. There has been no significant difference between fall and winter applications, and only slight improvement in seedhead suppression when both fall and winter applications are applied prior to a normal two-application spring program. Thus far, we have not observed unacceptable injury to Poa annua or creeping bentgrass, even when both fall and winter applications were applied. We currently are evaluating plant health products to promote potential winter stress defense with fall ethephon treatments.

Dramatic improvement

In seedhead suppression research at Virginia Tech in the past five years, adding early ethephon applications dramatically improved seedhead suppression over traditional spring programs alone in every comparison within 15 replicated putting green and fairway research trials across Virginia.

In the past two years, other university scientists have started evaluating these programs with reportedly similar results. Based on my correspondence with superintendents in the eastern United States and in social media discussions, it appears many superintendents also have adopted these programs with general success. Future efforts at Virginia Tech will include various tank mixtures and approaches to economical seedhead suppression on fairways and incorporation of other growth regulators, such as Anuew (prohexadione calcium), Trimmit (paclobutrazol), and Cutless (flurprimidol) into these programs on both greens and fairways.

Shawn Askew, Ph.D., is a turfgrass weed scientist at Virginia Tech. You may reach Askew at saskew@vt.edu for more information.

photo courtesy Shawn Askew