Q&A: Proxy for annual bluegrass seedhead suppression

Cark Throssell

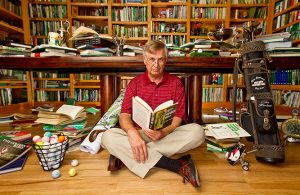

Zac Reicher, Ph.D., is a technical specialist with Bayer Environmental Science. He has more than 25 years of turfgrass research experience and has conducted many annual bluegrass control experiments on research plots and golf courses.

Q: What is the biggest frustration superintendents have when using Proxy?

Inconsistency of control from year-to-year is the biggest frustration superintendents have with using Proxy (ethephon). Because Proxy is effective only when applied before annual bluegrass seedheads emerge, making the initial application early enough in the spring has been a challenge.

Q: What is the recommended timing for Proxy applications?

Annual bluegrass seedhead initiation occurs in late fall. For an effective Proxy application, superintendents must apply it in the spring before they can see seedheads. Our observations in the field and research support applying Proxy in early spring. Our advice is to apply Proxy after annual bluegrass has started to green up, even if creeping bentgrass still is mostly dormant. If in doubt, make the Proxy application early, rather than delay it. The first application can be Proxy alone. Make a second spring application three weeks to four weeks after the first application, and include PrimoMaxx (trinexapac-ethyl) in most cases.

Preliminary research, especially at Virginia Tech, indicates that an additional Proxy application made in late fall, around the time of the last mowing of the year, improves control over spring-only applications. The following spring, make the first spring application of Proxy at the traditional timing suggested by a growing degree model, a biological indicator or based on the site history. Make a second spring application three weeks to four weeks after the first application, and include PrimoMaxx in most cases.

Q: What is a reasonable level of seedhead suppression to expect from Proxy applications?

Some superintendents consistently get more than 95-percent annual bluegrass seedhead suppression year after year, while others may get 90-percent suppression one year and 70-percent suppression the next year. Some of the inconsistency may be due to application timing each year and the size of the annual bluegrass seedhead crop. In years with abundant annual bluegrass seedheads, suppression may be slightly lower than in years with a low-or-moderate seedhead crop.

Also, seedhead suppression can vary from green to green or golf course to golf course, based on the unique microenvironment on a specific green or golf course. For instance, annual bluegrass seedhead development may be more advanced in south-facing areas, while seedhead development may be lagging in shaded areas. In this case, the application of Proxy might be perfect timing for some areas but not others, resulting in more annual bluegrass seedheads in some areas than others.

Q: Anything else you would like to add?

The newer application schedule of Proxy means that superintendents can combine it with other applications, such as snow-mold fungicides in the late fall, or with fairy ring/early season dollar spot fungicides in the spring.

As with all applications, applying Proxy uniformly is important. Be sure that there are no skips in the spray pattern. A skip will show up as a long, narrow band of annual bluegrass seedheads. Proxy is rainfast after two hours.

Where applicable, I recommend covering a 4-foot-by-4-foot spot with a piece of plywood in an out-of-the-way area on two or three greens while you spray so you can monitor the effectiveness of the Proxy applications. These untreated areas are good tools to use to sell the golfers on the importance of suppressing annual bluegrass seedheads.