Controlling ultradwarf bermudagrass diseases

Cottony white mycelium associated with Pythium blight may be observed in the early morning while moisture is present on the leaves.

Turfgrass diseases, including diseases of the newer ultradwarf bermudagrass varieties, need four conditions for development: a susceptible host (the turf), a pathogen, a conducive environment and time. Golf course superintendents have plenty of these four factors.

What they don’t always have is an accurate diagnosis of the disease giving them pounding headaches.

Is the plague of the week Pythium blight? Leaf spot? Root decline? Pythium root rot? Proper diagnosis must be the starting point for treatment, but once the disease is pinpointed, control options abound.

In an April 2018 GCSAA webinar, Maria Tomaso-Peterson, Ph.D., took listeners through the disease cycle and highlighted areas where the cycle may be broken to minimize disease incidence and severity. Tomaso-Peterson is a research professor in plant pathology at Mississippi State University and focuses her research on the novel fungal complex associated with bermudagrass decline on putting greens.

The proper befuddlement

To put webinar listeners in the proper mindset, Tomaso-Peterson quoted astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson. “If a scientist is not befuddled by what they’re looking at,” Tyson said, “then they’re not a research scientist.”

Befuddlement can be easily found when superintendents attempt to identify the cause of the diseases they see. The menu is long and confusing: an abiotic disorder, a fungus, a bacterium, nematodes, insects. More than a third of samples from greens examined by labs across the country show abiotic disorders, Tomaso-Peterson noted, but that leaves a lot of room for her specialty, fungal diseases. These diseases include Pythium blight, Pythium root rot and bermudagrass decline/take-all root rot.

Pythium blight on ultradwarf bermuda greens may appear greasy and black due to rapid foliar tissue degradation.

The first step for superintendents is to locate a turfgrass diagnostic service within their region, Tomaso-Peterson told Golfdom in a separate interview. “Identifying the disease, that’s No. 1,” she noted. But do superintendents always need a diagnostic lab? “I’ve worked with several superintendents over the years in diagnostics,” she said, “and once we’ve worked through the diseases on their golf course for three to four years, with the superintendents saying, ‘Oh, I think it be might be this,’ then sending it in for confirmation, they became very confident in knowing what the diseases were at their golf course.”

This confidence, however, is mostly related to foliar diseases like leaf spot, Pythium and Microdochium patch, Tomaso-Peterson said. “But when it comes to root diseases, that’s very difficult because all the root diseases develop symptoms that are similar… but most root diseases don’t occur in a nice little patch… They always have to get a diagnosis because we don’t know if it’s Pythium spp. in the roots or fungi or nematodes. So most of the diagnostic questions I’ve received in the past are root related because the superintendents pretty much pick up the foliar diseases once they go through a season or two.”

The loss of Nemacur exacerbated the situation, she said, and caused “ridiculous” nematode pressure, which has been lightened by the labeling of new control products, which “will lessen the number of nematode samples, which act in concert with these root pathogens.”

Pythium diseases

Numerous species of Pythium are associated with foliar, root and seedling disease. “Each of these diseases are distinct,” Tomaso-Peterson said. For example, Pythium aphanidermatum and other species are associated with foliar blight, P. volutum and others with root diseases, and many species cause seedling rot or damping off.

Pythium spp. “is not a true fungus,” she noted, “it’s in the kingdom Stramenopila and the phylum Oomycota. But because these organisms are not true fungi in the kingdom Fungi, the fungicides we use to control these Pythium diseases are specific for the Oomycota. And they have aquatic, amphibious and terrestrial habitats and are typically referred to as water molds.”

Pythium blight on ultradwarf bermudagrasses, despite nearly 30 years of experience with them, started showing up only about 10 years ago, Tomaso-Peterson said. The times for the disease are late summer, early fall and in some cases, late spring. It thrives in extended wet conditions and in saturated soils and rootzones in temperatures between 65 degrees F and the mid-80s F. In summer renovations from bentgrasses to ultradwarf bermudagrasses, grow-ins with high nitrogen inputs and heavy irrigation can create a “perfect storm” for Pythium blight, she noted.

Superintendents, especially those going from bentgrass to ultradwarf bermuda, need to understand the susceptibility of these grasses to Pythium blight and root rots, Tomaso-Peterson told Golfdom. “The thought was, ‘I’m going to bermuda, and I’m going to have minimal diseases and Pythium diseases are not going to be on the radar.’ But it needs to be on the radar, especially on converted greens that have been no-tilled into old bentgrass greens.”

Foliar symptoms of the disease on greens (especially dew-wetted greens) include greasy, black spots on greens surrounded by a white, cottony mycelium. “In fact,” Tomaso-Peterson said, “Pythium blight used to be called ‘greasy spot.’” These signs can be joined by prominent black lesions on folded leaves, notably on new growth. Only species of Pythium cause this black, water-soaked appearance with black lesions.

Other foliar tipoffs are distinct necrotic spots and patches with a dark border and necrotic streakingon greens. “As mowers move,” Tomaso-Peterson noted, “they deposit the pathogen — that’s why we see the streaking. And it’s as bad on ultras as on bents.” Reproduction is both sexual and asexual.

Foliar lesions associated with Pythium blight are often black, rapidly expanding across the leaf blade.

Disease management

Superintendents can take a scientific or non-scientific approach to managing diseases such as Pythium blight. The non-scientific approach is simple. “We can,” she said, “pray for sunshine.” For some time after the adoption of ultradwarf bermudagrasses this approach may have seemed to work, she noted, because “superintendents didn’t expect Pythium diseases on ultradwarf bermudagrass.”

And periods of sunshine after wet, damp weather can halt a Pythium disease outbreak. “It’s not that it’s not there,” she said, “it’s just that the sunshine and dry conditions shut it down.”

Cultural control practices include avoiding saturated soils and improving drainage, minimizing leaf wetness with wetting agents, thatch management along with topdressing, managing nitrogen, and when Pythium blight is active, mowing when greens are dry.

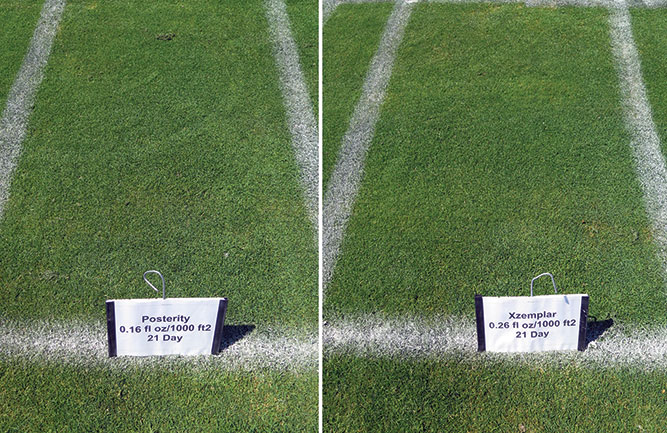

Developing a chemical management program also is important. Timing, application coverage, following

the spray interval and alternating modes of action using the FRAC code as a guide all are critical. And of course, follow all label rates.

The basics

Tomaso-Peterson has some advice for superintendents in all disease situations. “I recommend that superintendents do general nematode analysis to get a baseline count of nematodes on their greens. If they start seeing something off-color, or patches that might look like some kind of a foliar disease, they should go ahead and get a diagnosis so they can start developing their history profile for diseases. Once they do that, they can begin to understand what diseases might occur and at what time of year. They don’t want to play catch-up.”

Listen to Maria Tomaso-Peterson’s entire webinar.

Photos: Cory Messer (1); Alan Windham (2), Maria Tomaso-Peterson (3)